Christmas at the lake house had always looked good in photos and felt wrong in person. The wreath on the glass door matched the plaid runner down the cherrywood table; the candles were set at precise intervals like an ad, flames steady and photogenic; the crystal stemware reflected the tree lights in perfect little halos. But the warmth was staged, the timing off, like everyone was waiting for a cue that never came.

I sat at the far end near the old radiator—the one that still clicked every ten minutes no matter how carefully I cleaned and bled it in October. Outside, cold air sharpened the line between lake and sky. Inside, Lorna moved quietly along the wall, topping off water, adjusting plates the way she always had, pretending not to hear what families only admit in whispers.

My name is Danielle Reef—Dani to the people who remember me as more than an errand. I’m twenty‑four years old, living in Marietta, Georgia, when work requires me to be there, but this place in the foothills of Burke County, North Carolina, has been home longer than any street address. I know the smell of its crawlspace after rain, the places where the floor dips if you step before the nail line, the way late November light slants through the den and turns dust into glitter. I learned the house the way you learn a language—by repeating what you’ve heard and fixing what doesn’t make sense.

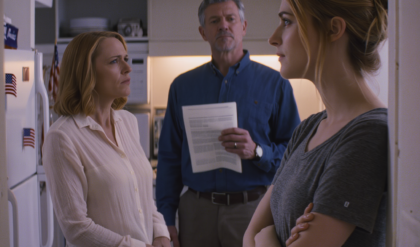

Across from me, my brother Marcus raised his glass with a little showman’s pause. He was born for head‑of‑table pronouncements: tailored navy suit jacket, subtle watch, hair smoothed like a statement. My sister Laura sat to his right, her shoulders pulled tight, chin lifted, the kind of smile that looks like patience from a distance and calculation up close. Mom folded her napkin with deliberate care, eyes down; Dad stared somewhere past the centerpiece as if the lake might answer if he squinted long enough.

Marcus tapped his fork on crystal the way people do in movies. “Let’s raise a toast,” he said, smooth as a radio host. “To the next chapter of our family legacy.” He looked straight at me when he said the word family, like a judge reading a name he’d already crossed out.

No one blinked. The room went heavier by a notch.

He went on, cheerful, casual, detonating between sentences. “After a lot of discussion, we’ve decided to sell the lake house. It’s time to let go, Dani. We all think it’s best you start the next phase of your life somewhere else. You’ve… held on long enough.”

The radiator clicked, right on time. I didn’t flinch. Didn’t argue. I reached for my water, took a slow sip, set it down, and folded my hands.

Marcus smiled like he’d just handed me a plate of hard truth and expected gratitude. “We’ve lined up a buyer,” he added. “They’re ready to move quick. This place could be a boutique resort by next summer. You’ll land on your feet, I’m sure.”

Laura nodded, as if she believed that, as if landing on my feet were something I hadn’t been practicing since I could reach a top shelf. Mom’s napkin turned again between her fingers. Dad didn’t touch his glass.

I looked around at the surfaces I’d scraped and sanded and stain‑matched—summer after summer, hurricane after hurricane. The wall by the stairs still wore a brighter rectangle where a family portrait used to hang; the mudroom baseboard had the careful caulk line I’d learned to make with blue tape and a patience I didn’t know I had at sixteen. None of that counted, of course. Not to the people who measured value by signatures and dinners with strangers who wanted to sit where we were sitting and call it a second home.

They thought I was a kid with a stubborn streak. A stray who stayed after Dad stopped asking where I was. A soft spot to absorb the chores nobody else had time to do. They mistook endurance for inertia. They mistook silence for consent. They thought I had no plan.

They were wrong.

I leaned back, gave Marcus the same easy smile he’d perfected since prep school, and said, “Sounds like a big move. Hope you read the fine print.”

He cocked an eyebrow. Laura’s fork went still mid‑air.

“I just hope,” I said, “whoever signed off on that sale knew who the legal owner is.”

For a moment, the candles looked like they flickered because the room did. Marcus looked at me the way people look at surprise bills—annoyed at the audacity of the number, convinced there must be a mistake.

Three years earlier I had worn a company badge and parked in the Reef Capital Reserve lot with a yellow tag that said Analyst in small print and Expendable in invisible ink. I was nineteen when I started working there between classes and twenty‑one when I learned how fast a door can close when someone decides you don’t need to be on the other side.

It began with numbers that wouldn’t sit still. Pension reports with names that slid off spreadsheets; account balances that gained and lost weight between versions. I brought a printout to Marcus, thinking maybe the system had hiccups. He clapped my shoulder with a smile that said both good catch and stay out of the kitchen. “Don’t stress the accounting, Dani. We got people for that.”

A week later my login failed. HR called it a restructure. I called it a courtesy performed by security as they walked me to the elevator. Laura wouldn’t pick up; Dad wouldn’t meet my eyes. By the time Mom asked me how I was sleeping, Marcus had already convinced Dad to sign a fresh will during what a physician later described as a cognitive fog episode—a phrase that tastes like paper when you say it out loud. My name fell out of the estate plan as if it had never fit.

They said I was erratic. Said I’d misused project budgets. Said I cried in client meetings. They said it with confidence and perfect posture and bad evidence. People believed them, because confidence is a currency and they’d been millionaires in it since the day they learned how to look at a room and decide who counts.

I left the city with a backpack and a borrowed toolbox. Picked up side work under a name nobody recognized—contracts, consulting, unglamorous fixes that made the month make sense. I kept my head down. I kept receipts. I kept breathing.

I didn’t plan revenge. I planned survival. There’s a difference no one sees until you hold it to the light and watch what shines through.

One night, hunched over the lake house desk with a lamp that hummed at certain settings, I scrolled through public filings to quiet my brain. That’s when I saw it—an innocuous line item that didn’t match the trust’s usual patterns. Marcus had refinanced the estate trust, not for the company’s health but to cushion his own. He’d dumped a seven‑figure stock position to cover margin losses, then mortgaged our history to stop the bleeding. The trust had already defaulted once.

That was the hinge. Whatever part of me had still been hoping the story would arc back to sanity snapped off and dropped away.

I learned how to read a title history like a diary. Learned which signatures belong on which lines. Learned how to trace offshore payments without a passport and how to file property claims with a pen that didn’t shake. I hired a former IRS auditor for six months and paid her in coffee, cash, and the satisfaction of teaching a kid to see the red flags in a field that looks green from far away. I set up Black Birch Holdings LLC through a friend’s firm in Delaware and made sure nothing spelled our name unless a judge ordered it to.

They thought I was locked in the crawlspace with a wrench and a flashlight. In reality, I was mapping out the house they’d built on sand.

So when Marcus declared the sale tonight—with his confident little pause and his boutique‑resort vision—I watched the performance and waited for the part where he asked me to clap.

I didn’t clap. I reached into my bag and set an envelope on the table.

Laura frowned. “What is this?”

I didn’t answer. Not yet. Not until they let the facts in.

Marcus flipped the flap with that same easy calm he used to tell people they were redundant. He skimmed the first page and smiled like he’d found a typo to exploit. “This is nonsense,” he said, closing it. “You can’t just claim ownership of the house.”

I raised an eyebrow. “That’s the deed transfer from the foreclosure sale recorded in Burke County six months ago.”

He scoffed. “No court would uphold that. The property belongs to the family trust.”

“That trust,” I said, keeping my voice conversational as if we were discussing weather, “was liquidated after a margin call.”

His smile twitched. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Do I not?” I leaned forward. “Because when your firm defaulted on the refinance, the trust became collateral. The bank moved. The property was listed. Someone had to show up to bid.”

Mom’s napkin drifted from her hand to the floor. Laura’s color thinned.

“You’re bluffing,” Marcus said.

“Am I?” I slid a second stack of paper across the table. “Title history. Transfer of ownership. Wire confirmations. And you didn’t even notice the address change on the property tax records. Too busy lining up your fake buyer.”

He stood. Paced. Turned his back to the tree. “I had a deal with a developer,” he said. “They were ready to make an offer.”

“You were trying to sell what you didn’t own,” I said. “There’s a word for that.”

Mom looked between us like tennis at match point. “Why would you do this, Dani?”

“I didn’t do anything to you.” I kept my hands flat so they wouldn’t shake. “I followed the paper trail you ignored.”

“You blindsided us,” Marcus snapped. “You cut me out.”

“You cut me out,” I said, heat finding a clean edge in my throat. “You thought I’d crawl away and rot. While you were holding court, I was picking up pieces.”

Laura’s voice landed quiet. “So… what now?”

“Now,” I said, “we talk about who built this family and who tried to bury it.”

I reached back into the bag I’d brought into this room like a lifeline and set one more folder beside the candles. “This is the part you didn’t plan for.”

Marcus’s face went a shade redder. Laura looked like she wanted the chair to swallow her. Dad’s expression didn’t change, but his knuckles flexed against the table edge.

“Here’s the timeline,” I said, steady, the way you read instructions before you wire a panel. “Your firm tanked, Marcus. You lost big on those energy stocks. You used the family trust as collateral to cover your margin call. The bank took control when you defaulted. While you were scrambling for investors, the house was listed quietly. I showed up. I bid. I bought it—legally—through Black Birch Holdings LLC.”

Marcus shook his head. “Twisting facts doesn’t make them true.”

“Facts don’t need me to twist them,” I said. I turned to Laura and slid a fresh stack toward her. “These are yours. Internal memos. Compliance reports. Same file, three versions. Your signature. You blocked my access to the company records and told the board I was mentally unfit.”

Her hands trembled as she pushed the papers away like they burned.

“And this,” I added, laying down one last stack bound with a clip, “is where the trust money went. Wire transfers to accounts in your orbit labeled consulting fees. More than $2 million, Marcus. All under your login.”

He laughed, a sharp sound with no humor in it. “Fabrications. No one will believe you.”

“They don’t have to believe me,” I said. “They just have to read.”

Silence settled over the room like snow. Heavy. Sound‑absorbing. Final.

I looked at Dad. He had not moved in minutes. His glass sat untouched, a ring of water forming beneath it. I held his gaze until he had to look back. “You knew,” I said. “You knew, and you thought I couldn’t prove it.”

His jaw worked once. He opened his mouth and closed it without a word.

“You let Marcus run wild with the trust,” I said, softer. “You let Laura falsify records. And when I asked questions, you backed their story instead of mine.”

Mom’s eyes filled—anger, fear, grief, I don’t know. She didn’t speak.

I spread the documents the way dealers lay cards you can’t unsee. “This isn’t revenge. It’s restitution. Every page is notarized. Every filing is public record. You can deny the sun at noon, but you’ll still get burned.”

I reached for the deed transfer, held it up so the seal caught the candlelight.

Marcus slammed his fist into the table. The sound rang tinny, like a cheap cymbal.

Laura didn’t look up.

Dad turned toward the window, toward the reflection of his own house looking back at him through glass, as if that version might know what to do.

Mom’s fingers finally found one page and dragged it closer. “My God,” she whispered.

I let the quiet sit until it settled where it needed to. Then I said, “There’s one more piece.”

Laura’s head snapped up.

“Aunt Ruth,” I said, and set a heavier folder on the table. “Her will.”

Laura shook her head before the word finished. “No.”

I opened the folder. “Ruth’s signed copy never left her possession until the night she died. The one filed at court—the one that leaves everything to Marcus—wasn’t hers.”

“That’s not true,” Laura said, too fast.

“Isn’t it?” I slid out a still from hospice security, time‑stamped, grainy, damning: Laura slipping into Ruth’s room at 2:00 a.m. without a nurse. Then I set a stapled statement beside it. “Night shift nurse. She noticed the medication log in the morning—morphine dosage off the chart. Not a normal spike. Not accidental.”

Mom gasped. Her hand went to her mouth and stayed there.

“And this,” I said, placing one last sheet, “is the toxicology report from Ruth’s chart. Elevated levels. Three times the prescribed dose. The attending flagged it, and that note didn’t make it into the official file you submitted.”

Laura’s voice splintered. “She was dying. She was in pain.”

“She was lucid,” I said. “She emailed me three days before she passed.” I reached into my jacket, set a small USB drive on the table. It hit the wood with a soft click that sounded louder than it should. “She sent me her will—the real one. It names me as her successor co‑owner. She recorded a video message. Her words. Her voice. She wanted me to keep the estate safe from all of you.”

The blood drained from Laura’s face. Marcus turned on her, eyes like lit fuses. “What did you do?”

“I—” She couldn’t land the syllable.

“Save it,” I said. “This stopped being a family feud when you filed at probate with paper you knew wasn’t clean. If the District Attorney decides the nurse’s statement plus tox is enough to open a case—” I tapped the USB. “—that’s a police matter.”

Dad finally spoke, gravel at the bottom of a well. “You’d drag your own sister into court?”

“She dragged herself,” I said. “She forged a path and walked it.”

Mom looked at Laura like she was seeing a stranger wearing her daughter’s face.

Marcus’s composure frayed at the edges. “You’ll regret this,” he hissed. “You don’t know the damage you’re doing.”

“Oh, I know,” I said, sliding the drive back into my pocket and stacking the testimony I’d laid out like tiles. “I’m turning on the lights.”

I planted both palms on the table and looked at each of them in turn. “This house is mine. The will is mine. And everything I’ve shown you is admissible.”

The room held its breath.

That’s when the knock came. Three short wraps. No rush, no hesitation.

I turned toward the front hall. Through frosted glass, two Burke County deputies flanked a man in a dark jacket with a federal badge clipped to his belt. I opened the door.

“Danielle Reef?” the agent asked.

“Yes,” I said. “They’re inside. Everything’s ready.”

He stepped past the threshold, the deputies behind him. “We have arrest warrants for Marcus Reef and Laura Reef on charges of fraud, embezzlement, obstruction of justice, and falsification of legal documents.”

Marcus backed away, panic blooming like heat under his collar. “This is insane. You can’t arrest us in our own house.”

“It’s not your house,” I said, stepping aside as the cuffs closed. “Not anymore.”

Laura didn’t speak. Tears landed silent on crystal as a deputy read her rights.

Dad pushed up from his chair, face flushed. His hand pointed at me like an accusation could erase ink. “You self‑righteous little— Look what you’ve done. You ruined this family.”

I met his eyes and didn’t look away. “No,” I said. “I’m cleaning up.”

He opened his mouth and nothing came. Sometimes silence is the only honest sound a person has left.

They led Marcus and Laura past the tree—the one still blinking like the string lights didn’t realize the power had already shifted. Mom didn’t move. Her hand gripped the back of her chair so hard her knuckles blanched. She didn’t speak.

The front door closed behind badges and uniforms. The room deflated. Dad sank back into his seat and stared as if the air in front of him might assemble into an apology if he waited long enough.

In the kitchen doorway, Lorna stood half in the shadow, two clean glasses in her hands. She stepped forward, set them down, and rested a palm on my shoulder—a steady weight I didn’t know I needed until I felt it.

“You all right?” she asked.

I nodded. “Been waiting a long time.”

She squeezed once. “Your aunt would be proud.”

I believed her, because Lorna didn’t say things she didn’t mean. She’d been here for thirty years—through storms and repairs and the kind of holidays that end with plates washed in silence. She didn’t have the money my family liked to flash or the names they liked to drop. She had the keys. She had the lists. She knew when the roof last saw a nail and who lied at dinner. She saw me when the rest of them looked past me and pretended that was the same as love.

Outside, the patrol tires crackled over old gravel and fresh snow. The lake breathed mist. The radiator clicked, a little metronome that had kept time through years of pretending we were fine.

I didn’t feel triumphant. I felt… clear. The first breath after the room stops spinning.

Three months later, the lake house didn’t smell like old money and lemon polish. It smelled like sawdust and solder, motor oil and coffee that had been fresh an hour ago and still did its job. The dining room where Laura once lifted crystal and lied to my face housed drafting tables and 3D printers that hummed like bees with purpose. The music room Marcus used to show off his speakers held workbenches and clamps and the kind of tape you learn to tear with your teeth when your hands are busy.

We opened the Reeves Center quietly—no ribbon, no speeches, no photographer arranging us by height. Just a new lock on the gate, a paper taped inside the office door with weekly rotations for six young men who’d signed up to learn how to tear down a Honda Civic and put it back together, how to square a board, check a level, program a printer that could make a bracket strong enough to hold a shelf and a plan. We started small on purpose. Lorna ran mornings with a clip‑board and a patience that made teenagers stand up straighter when she walked past. I moved into a studio above the north wing—just big enough for a bed, a desk, a window with a view of water, and the kind of quiet that doesn’t feel like being forgotten.

On a Wednesday that smelled like rain, I walked into the west hallway in time to see cousin Kevin—who used to fix everything badly—running cable beside a volunteer electrician who showed him how not to burn the place down. Kevin looked up, grinned, and wiped his hands on jeans that would never be truly clean again.

“Almost done,” he said. “We’ll have the west wing lit by lunch.”

Progress isn’t pretty. It’s conduit dust and mislabeled boxes and coffee stains on a map. It’s counting screws into a palm, learning the difference between a number two Phillips and wishful thinking. It’s the look on a kid’s face when the car he’s been swearing at coughs, catches, and runs.

At night I wrote reports and filed grants and answered the kind of emails that sound polite until you read them twice and realize they’re asking whether you know what you’re doing. I attached documents with stamps and signatures and a deed with a seal that had already withstood louder doubts than theirs. Then I stood on the porch with a mug while the lake pulled night over itself like a blanket and let the temperature drop the noise out of my head.

Sometimes I thought about the Christmas tree, blinking like nothing had changed while everything did. Thought about Dad staring at glass because he couldn’t look at me. Thought about Mom twisting a napkin as if nerves were a skill. Thought about Marcus’s laugh cracking in the middle. Thought about Laura’s silence when the cuffs clicked.

I didn’t celebrate. I didn’t post. I put my hands on the work and kept them there.

A week into spring, I found myself under the house again, which felt like closure even if I didn’t believe in that word. The crawlspace smelled like it always did—cold earth, old wood, the faint sweet rot of something that needed fixing soon. I wore a headlamp that made the world a little tunnel and scooted on elbows toward a pipe I’d been ignoring. I knew this house the way you know a person you’ve had to forgive without hearing the words. I loved it the way you love something that asked you to be strong before you were ready and turned you into the kind of person who can be.

Upstairs, a printer whirred. Someone laughed. Lorna called for a sweep. The radiator clicked.

I backed out of the tunnel and stood straight under a ceiling that used to feel low and now just felt like shelter.

There was no moral to extract and frame. No neat lesson you could fit on a page without lying. Just this: I didn’t turn the other cheek. I didn’t start a war. I turned on the lights. And when the room showed me what it was, I made a new one inside it that worked.

People like to say blood is thicker. They say it like a spell. But blood isn’t a contract. It’s a fact. What you do with it is the story.

On the first truly warm evening of the year, we rolled the garage doors open and let air shoulder its way through. Kevin tuned a small engine with a patience I hadn’t seen in him since we were kids. A student named Ty—eighteen, quiet, eyes like he’d seen enough—calibrated a printer bed with the kind of concentration that makes silence feel like applause.

Lorna brought out cups and a pitcher of water that tasted like task lists finished. She stood in the doorway and took it all in the way people look at finished rooms in magazines. Then she turned to me the way people look at home.

“Not bad, Dani,” she said.

“Not bad,” I agreed.

“Your aunt would be proud.”

“I know.”

The lake took the last light and made it silver. Somewhere a door shut. Somewhere a new plan started.

I thought about that night at the table, the staged perfection and the way the whole scene tilted when paper met wood. I thought about twenty‑one and nineteen and the thousand days between. I thought about every time someone told me to be reasonable and wait my turn. I thought about how much work there is in a word like keep—keep the receipts, keep the faith, keep going.

The radiator didn’t click. For once, it had nothing left to say.

We kept going.

The days found a rhythm that didn’t need permission. Morning check‑in on the whiteboard we salvaged from the office upstairs. Brooms along the baseboards. A roll call that sounded like possibility: six names, one syllable after another, all of them showing up on days nobody would have blamed them for staying home.

Lorna started each day the way she’d ended a hundred dinners—straightening, refining, making sure the small things pointed the big thing in the right direction. She kept a stack of index cards in her sweater pocket: inventory on one, chores on another, a scribbled reminder to pick up HVAC filters before Friday. When she walked the floor, shoulders squared, the room seemed to remember how to behave.

I learned what leadership looked like without a stage. It was a trash bag tied off neat at the end of a shift. It was the way a kid handed another kid a socket before he had to ask. It was letting quiet be quiet instead of filling it with a speech no one needed. It was writing policies on a cork board in Sharpie—no cursing at people, safety glasses always, respect the tools and the hands that use them—and watching those rules go from ink to reflex.

We didn’t talk about the arrests. Not in front of the kids. The house had ears, and it had heard enough. If someone asked why the dining room looked like a design lab, I told the truth the way you tell a story that doesn’t enlarge the villain: the place needed a purpose and we gave it one. The rest belonged to paperwork and clocks and people whose job it is to sort out what happened after the metal closed around wrists.

At night, when the quiet stretched and the lake took its color from the moon, I did the kind of work nobody claps for. I learned to love the ledger—columns behaving, decimals lined up like people waiting their turn. I reconciled bank statements that didn’t argue with me. I checked the title binder the way some people check baby monitors, assuring myself the pages still held. The seal on the deed felt as solid under my thumb pad as it had the night I first set it on the table—raised, official, a small circle that said we looked and we recorded and this is real.

Sometimes I opened the folder with Aunt Ruth’s name and let the papers breathe for a minute, not because I doubted them but because breath matters. I didn’t replay the hospice footage. I didn’t need to. The still frame lived behind my eyes when I let it. Instead I replayed the steady parts: the way Ruth’s voice didn’t break in the video she’d sent me, the precise way she pronounced my name like an act of custody. Keep the estate safe, Dani. Don’t let it turn into a stage set. Make it work. Not a lecture. A charge.

Work has a sound. In the garage it was the soft ratchet of a socket and the thrum of a small engine learning to run without complaint. In the lab it was the steady punctuation of printer heads laying down filament, one patient line at a time. In the hallway it was Lorna’s shoes and the sweep of a broom. In the kitchen it was the coffee machine saying ready in a language that needs no translation.

On afternoons when the sky refused to pick a weather, I took a coil of Romex from the supply closet and walked the west wing, mapping runs we’d half planned on legal pads. Kevin kept pace, thumbs hooked in his tool belt like somebody who finally believed he belonged in the company of work. He’d ask questions with his chin, and I’d answer with a finger’s point or a nod. The electrician who volunteered on Wednesdays showed us clean ways to make a turn, how to staple without bruising the sheath, how not to push your luck in panels.

We didn’t have uniforms, so we wore evidence instead: pencil behind an ear, dust on a shoulder, a crescent of grease along a wrist. My hands stopped looking like they belonged to a girl who fixed other people’s problems and started looking like they belonged to a woman who built the room where problems got undone.

When the students hit a snag, they looked at me the way people look at a manual they aren’t sure is written in their language. I made my voice practical and left the sermon out of it. “Back the screw out three turns, set your bit straight, don’t strip it. Slow is fast. Measure the board, then measure the reason you want it that length. Both matter.”

Some afternoons a sound would surface from memory—the click of that radiator in the dining room—and for half a breath I’d be back at the table, watching a performance try to pass as a conversation. That click had been a metronome for a song I didn’t want to learn. Now the house had a different beat. The shop clock ticked. The sawdust settled. The compressor cycled. The voices that rose did it for reasons that didn’t require applause.

I avoided the den where the tree had stood that night. Not because I was afraid of it, but because rooms keep echoes, and I wanted the echoes that helped. When I did pass through, I turned on the lamp and left it that way for a minute—a small practice in remembering that light is a choice people forget they have.

On the kind of evening that tricks you into thinking the cold is done, I walked the perimeter with a clipboard and a flashlight and marked the places water still liked too much. The lake sends up mist when it feels like it. The ground answers back in seams and cracks. Fixing a place requires listening to the arguments it has with time. You don’t win those. You bargain.

The Reeves Center didn’t advertise. It didn’t need to. People who have a use for a place like this tend to find it the same way I found the filings that changed the room that night—quietly, by looking longer than seems reasonable. Word’s a river anyway. You don’t push it. You stand where it’s moving and make space.

A month into the semester of our own making, I set the students to tear down the Civic we’d bought with a check that didn’t bounce. We laid every part on labeled cardboard: intake, throttle body, radiator, alternator, starter, plugs, wires, the whole layout like a diagram that finally told the truth. Two of the kids stared at the timing belt like it was a dare only a fool would take. I handed them patience and nitrile gloves and the piece of advice someone should have given me sooner: “The only way through it is through it. We’ll do it together.”

We built jigs in the carpentry lab—nothing fancy, just squares that stayed square and a sled that made repeat cuts behave. The first time a joint seated clean, one of the boys grinned like he’d been handed permission to exist in a room people usually tell him to leave. It’s a look you don’t forget if you ever wore it yourself.

Nights stayed mine. I wrote thank‑you notes with ink that doesn’t smear and ran the numbers twice. I set aside ten minutes to stand at the upstairs window and watch the lake unspool its version of the day. The water kept secrets for the people who needed it to and told the rest of us to get on with what we were doing.

People like to ask if I felt vindicated. The honest answer is less than they think. Being right is a thin blanket on a cold night. Being useful is a furnace you can feed.

I did not check the news for updates more than once or twice. I did not mark calendar dates that didn’t belong to my work. The part I needed to do, I had done: I turned on the lights and put the documents on the table. Other people have jobs too. I let them do them.

When doubt tried to make a case in the back of my head—what if I had pushed too hard, what if I hadn’t pushed hard enough—I answered it with the rhythm of a day that held, with receipts that don’t flinch, with the simple proof of a classroom that used to be a dining room and now held futures instead of speeches.

On a Thursday morning that smelled like wet pine, Kevin flipped the breaker on the west wing we’d re‑wired slow and correct. The lights came up in a ripple from door to far wall. He held his breath until the last fixture answered, then let it out in a laugh that didn’t ask permission to be heard.

“Looks right,” he said.

“It is right,” I said.

We left them on for the rest of the day, not because we needed to but because we could.

Sometimes I wrote to Aunt Ruth without touching a keyboard. I wrote in the language of lists and measurements and hands that had learned to steady. We kept your promise. The place works. It holds. It teaches. It returns what it’s given, not to the loudest bidder but to the ones who show up. I said yes to the kind of stewardship that doesn’t make headlines. You’d recognize the feeling of it like you recognize your own signature.

I remembered details I hadn’t let myself keep before—the citrus hand soap she preferred, the way she would straighten a frame and then move it back because a small imperfection kept a room honest, the sound she made when she tasted coffee that hit the mark. If grief is a ledger, those went in the column that balances.

The USB stayed in the office safe with the papers that first shifted power. I didn’t need to see the video to hear her tell me again to keep the estate safe. Some instructions are muscle memory by the second repetition.

There’s a line people cross when they decide to protect something for real. It’s invisible until you remember yourself before you crossed it. Then it’s all you can see.

Late one Friday, I found myself under the house again. Not for a crisis. For a check. The crawlspace held cool air like a held breath. I slid forward on a scrap of cardboard, headlamp drawing a white circle ahead of my hands. The joists looked like spine. The pipes looked like arguments that had been settled for now. I tapped the copper where it elbowed and listened. No complaint. I tightened a strap because it calmed me to do it. I backed out slow, a little dusty, a little steadier.

Upstairs, the radiator waited me out. I bled it one last time, a quarter turn that let the persistent pocket of air admit it had lost the argument. The click didn’t come. The quiet did. It felt like a room deciding to tell a different story.

I stood there longer than necessary, wrench in hand, until Lorna’s voice carried from the hall.

“Dinner,” she said. “Don’t make me come get you.”

I smiled and put the tool away where it belonged.

We ate at the work table that used to host announcements about legacies. The food wasn’t plated like an ad. It was good anyway. We didn’t toast to the next chapter. We just turned the page by living it.

After, I washed the pans because Lorna always did and because the best thank‑you you can say to a person like her is a job finished clean. She dried. Kevin carried the trash out. A kid who’d once sworn at a stripped screw fixed it without drama and left the screwdriver where it belonged.

No applause. No performance. Just a place doing what we said it would.

On a Sunday that smelled like a hardware aisle, I took a notebook and walked the property line with my boots sinking a little in the places the ground kept secrets. I wrote down what the fence would need when we could afford to care about it. I wrote down how far the oak’s roots had pushed toward the old septic cap. I wrote down the angle of the roof that would take solar best if that ever became a line in a budget that didn’t hurt.

Back inside, I tacked the list to the cork board under a heading that didn’t ask for applause. Next.

If anyone had asked me, I would have said the ending had already happened—the night paper hit wood and the room learned what light felt like—but not all endings are a door closing. Sometimes they’re a room remembering what it’s for.

We didn’t hold a ceremony to mark it. We didn’t need a ribbon or a speech. The house had been a stage long enough. It wanted to be a shop, a lab, a hallway people pass through on their way to better rooms.

One evening the air went from afternoon to dusk without asking permission, and the lake put silver where the day had left blue. Lorna stood in the doorway with the lights of the west wing at her back. Kevin checked the calendar and whistled low like a person who has begun to trust tomorrow. The printers finished a job and lifted their heads like animals who know where they live.

I walked to the window at the end of the corridor—the one that frames the water like a photograph—and let myself remember the whole story without stopping at the parts that used to take my breath away. The table. The envelope. The USB landing. The badge at the door. The cuffs glinting by a tree that kept blinking like it was practicing hope. The way the floor felt under my shoes when the room became honest. The way paper can be a light switch if you collect it carefully enough.

People talk about closure like it’s a single act. I’ve learned it’s many small ones done correctly. A screw set flush. A wire dressed neat. A rule written clear. A hand offered to steady and then removed when it’s no longer needed.

I shut off the lights one by one, leaving the west wing for last, not because I liked the drama of it but because endings deserve to be tidy. When I hit that final switch, the room didn’t feel empty. It felt ready.

At the threshold I paused and listened because houses answer if you let them. No click from the radiator. No hum from a tree covered in glass ornaments trying to pretend it’s warm. Just the sound of wind across water and, somewhere close, tools sleeping with their edges guarded.

I locked the door and put the keys in my pocket. The same pocket that used to carry a badge I wasn’t allowed to use and a phone that rang with instructions that negated what I knew was right. Different weight now. Earned.

Outside, the cold held nothing against me. It was the kind of cold that tells you to move so you do. The porch boards took my steps and did not creak because I had tightened the screws last week while I was on hold with a vendor who wanted to know if we planned to be around long enough to matter. I had told him yes. I hadn’t raised my voice. I didn’t need to.

I closed my eyes and saw Aunt Ruth’s careful signature. I opened them and saw the lake keep its promise to be exactly itself.

“You keep watch, I’ll keep working,” I said aloud, to the water, to the house, to the woman who had trusted me across a state of mind and a state line. Nobody answered. That’s how you know the truth is settled. It doesn’t argue back.

When I went upstairs to the studio, the window held the last thin reflection of the day. I set the ledger on the desk and wrote the only line that fit: We kept it safe. We made it work. Then I put the pen down and let the quiet do the rest.

I lay on the bed and listened for the click out of habit. It didn’t come. For once, there was nothing left for the house to say. Only what it would do tomorrow.

The radiator stayed silent. The lights we’d turned on stayed on where they needed to. The rest could rest.

We kept going.