I didn’t so much hear the chandelier as register the vibration of it, a tiny tick running through the ceiling plaster and into the bones of the room. The table had that staged radiance my mother loved—silver catching lemon slices like tiny suns, salmon arranged as if it could still swim across the platter, asparagus curled into ribbons that suggested effort disguised as ease. Elaine Bennett had buffed the forks until they flashed our faces back at us like coins. She loved reflections. She loved the version of us that could be polished.

My father, Robert, leaned forward with his napkin still folded like a card he had not yet decided to play. He didn’t cough to clear space. He didn’t preface. He simply lowered his voice, and the quiet was louder than any toast.

“Lucy,” he said. “The two hundred thousand dollars I sent you—where is it?”

Movement stalled. A hundred tiny gestures stopped mid‑flight—forks hovering, a glass tilting, breath held. Aunt Marjorie’s wine became a paused ruby. Across from me, my brother Jason’s smile drained by degrees, like someone dimming a room by turning a switch in slow motion.

“What money?” I said, not because I didn’t know the number but because the room needed a straight edge and I had brought one.

The chandelier kept up its insect hum. The taper candles gave off a thread of sound, wicks whispering to their own flames. Outside the windows, Portland seemed to draw in its lungs. The Douglas firs along the fence line looked like witnesses who had done this before.

I set my phone on the linen. The glow washed my dinner plate in a cold square. The folder I’d built waited where I’d left it: timestamps, transfers, login trails, two‑factor pings, and a modest gallery of receipts. I slid the phone to my father. The air changed key—curiosity with dread braided through it, the pullback in the ocean before something large arrives.

His eyes widened in a way I had seen on job sites when a beam was not where the math said it should be. He hadn’t expected me to arrive with a ledger. He should have.

The night before I’d been in my small Seattle apartment, a place that smelled faintly of steam and cedar from the old pipes. Fabric samples had taken over my kitchen table—charcoal twill, a pearl‑gray that felt like breath, silk with a soft shine that reads as honesty rather than show. My laptop was split between a marketing draft and a vendor invoice. The coffee went cold twice. I reheated it twice. The first pass never decides anything for me. I built the life where I can bear my own weight—no allowances, no parental loans, no secret safety net.

Dad liked to claim that was why I reminded him of himself. He’d turned a garage into RB Bennett & Sons, a small construction company with one son and a plural that doubled as a wish. He ended our calls with the same four words—“I’m proud of you.” He never said it to Jason. The tone was different with everyone else. That wasn’t favoritism. It was fluency. Work recognizes work.

Jason was beautiful in a way that photographs reward—good light, decent angles, not much story underneath. He was three years older and full of projects that looked like a lifestyle more than a plan. A winery venture. A crypto thing with a logo that tried too hard. A boutique gym perfumed with eucalyptus and the promise of becoming the person you post. Money went through him like water through cheap cloth. Mom called it learning. I called it weather. You secure loose things when Jason blows through.

A week before the party, Jason called with his voice ironed flat. “Hey. Dad isn’t feeling great. Better skip the anniversary dinner.”

“Skip?” I said, staring at an email from Dad about the case of Willamette Valley Pinot he’d ordered for the toast.

“He’s exhausted,” Jason said. “It’s best if you don’t come.”

It felt wrong the way a table wobbles on one short leg. So I called the person who taught me to check the level before I nail anything down.

He answered on the second ring. “Lucy! You’re coming, right? Wait till you see what your mother did to the dining room.” He lowered his voice for the private joke. “You know how she gets.”

That was the moment Jason’s story fell apart.

On the flight south I tried to practice generosity the way you stretch before a run. Maybe he wanted the night to himself for once. Maybe he was protecting Dad’s rest. Maybe Mom didn’t want to risk a scene. But something heavier rode along—this dinner would be about control, not celebration.

The Bennett house looked the same as it always had: white clapboard, hedges trimmed to the inch, the transplanted pine‑candle smell Mom bought by the case so December could last all year. She hugged me with choreography. Jason stood behind her like a stage direction.

“You made it,” he said, smile a notch too wide. His eyes were hungry and watchful, a man feeling around for the loose nail.

It had been years since I felt like a guest in that house. My old room still held the bed frame Dad made from salvaged oak. The window still framed the sliver of sky where fourteen‑year‑old me timed the streetlights and pretended the city blinked just for me.

Morning arrived as bacon and competence. Mom moved through the kitchen aligning frames and centering candlesticks like she was adjusting exhibit labels. That wasn’t hospitality; it was curation. Dad ate like a man who still lifted his own equipment. He looked fine—brown forearms, steady posture, the kind of tired you earn and can count on. Not sick. Not whatever condition Jason had tried to sell.

When Dad stepped out to take a call, Mom tipped toward me like we were sharing a secret. “Let’s not talk work or money tonight,” she said lightly, but fear had its teeth on the words. “Your brother is under a lot of stress.”

“From what?” I asked.

“You know Jason,” she said, then selected a lie that fit poorly. “He’s figuring things out. Don’t make the evening tense.”

Her manicure had a chip. That told me more than the sentence did. Nothing chips on one of her showcase nights.

Later, while I laid out cutlery to her exact spacing, Jason hissed into a phone in the other room. “Next week. I said next week. Don’t call me again.” He hung up when he saw me.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Business,” he said too fast. “You wouldn’t get it.”

After he walked out, I noticed an envelope on the counter from the firm that handled my father’s accounts. Not Jason’s. Dad’s. A little door in my stomach opened onto cold air.

That night, as guests crossed the threshold—neighbors, Dad’s foreman in a tie that looked like a dare, Mom’s book club with smiles that counted—I slipped upstairs. An alert burned on my lock screen: transfer confirmation. Two hundred thousand. Completed. My name in the memo line. The money had moved out of a joint account I hadn’t seen since college. The origin tag: Jason Bennett.

I spent the night teaching my fear to walk a straight line. I traced the logins, chased the IPs, matched the two‑factor timestamps to Jason’s number lighting blue. Small test deposits, then the audacity of the big pull. The signature was digital and wore my name like a borrowed coat.

At dawn I set the phone on the counter in front of my mother. “Did you know?”

“Know what, honey?” The voice she uses on realtors and waitresses.

I turned the screen toward her. The figure glowed like a wound. Something in her face snapped taut and then chose softness instead.

“Lucy, please. Your brother was drowning. It was temporary. He promised he’d put it back before anyone noticed.”

“Before who noticed?” I asked. “Dad, or me?”

“You’re so independent,” she said gently, as if complimenting a stranger’s dog. “You wouldn’t miss it. Jason needed help.”

That sentence hit with more force than a slap. You wouldn’t miss it.

I left before I used words I couldn’t put back.

Aunt Marjorie poured burnt coffee across a counter that had seen every kind of conversation. Her diner’s sign had been fading since the late eighties and she refused to repaint it for reasons that sounded like religion.

“I figured,” she said when I told her. She produced a manila folder like a magician who specializes in receipts. “He came in last month bragging about a deal. Paid with hundreds. I kept copies.”

Inside: watches, a hotel bill with tasteless ambition, dinners meant to look like networking and smell like desperation. I photographed everything and called Caroline Ross, my father’s attorney and my old friend who can fit case law into a cardigan.

“This is clean,” she said. “Identity fraud, unauthorized transfer. If your father believes you took it, you need to put the truth on the table.”

“Not yet,” I said. “Not until they’re all in one room.”

“Then print your proof and set it on the linen,” she said. “And brace yourself.”

I had already braced.

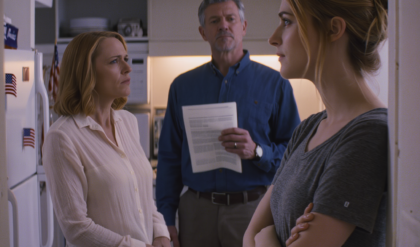

And so here we were: cake still a possibility, air ready to be one thing or another. Dad’s question landed. The lie finally had to stand up.

“I didn’t receive your money,” I said. “If you sent it, it didn’t reach me.”

“I have the transfer,” Dad said, anger strangling confusion. “Your name. Same bank.”

“Then check who else had the key.”

Mom stiffened. “Robert, not here.”

“Why not?” he asked. “If something’s wrong, we correct it.”

Jason set his fork down like it might discharge. “Dad, it’s not a big deal. I can explain.”

“Explain which part?” I asked. “The transfer in my name or the hotel you treated yourself to after?”

Dad’s head snapped toward him. “What is she talking about?”

I slid the phone back. Receipts. IP logs. The two‑factor history with Jason’s number blinking proof.

The color left my father’s face the way tide leaves stone. “Jason,” he said. The name did what verdicts do.

“I borrowed it,” Jason said, voice thin. “I was going to replace it.”

“You stole from your sister,” Dad said, iron showing. “And you forged access to do it.”

Mom surged to her feet so fast the chair skidded. “Robert, stop. He made a mistake.”

“A mistake?” Dad said. “Elaine, you knew.”

Her mouth started to form a no and then chose the truth. “He was sinking. I thought—if Lucy never found out—”

“You signed my name,” I said quietly. “And watched while I was put on trial over dessert.”

Stillness developed a texture. Guests stared at their plates with exaggerated interest. Aunt Marjorie looked at Jason like she was searching for the boy who used to leave crumbs in her sugar caddy.

Dad pulled out his phone and spoke like a man choosing his footing. “I need to report a theft. Two hundred thousand dollars.”

Mom’s sound was steam finding a whistle. “Robert, don’t.”

“He did this,” Dad said without looking at her.

Jason didn’t run. He didn’t ask. He moved as if each step weighed exactly the right amount. Mom followed him down the walkway with pleas that met the calm professionalism of officers who have escorted this kind of damage before. Dad signed the paperwork with his jaw set. When he finally met my eyes, his were full of gravel.

“I’m sorry,” he said. It cost him to say it.

“You believed what you were told,” I said. “You had reasons.”

He reached for my hand. I let him hold the fingers for a beat and then withdrew. For twenty‑four hours I had been my own hand to hold. Muscle memory is stubborn.

“You asked what I did with your money,” I said. “I protected it.”

They walked Jason out. The front door closed on my mother’s breaking. Patrol lights stroked the window, making ghosts of us all. The chandelier resumed its indifferent hum.

Marjorie stood and put a palm on my shoulder. “You did right,” she said into my hair.

“Maybe,” I said. “It doesn’t feel like a victory.”

Dad sat down hard. Outside, the cruiser’s lights made a traveling river along glass. I looked at the folder on my phone—the tidy archive of a betrayal—and thought about how quiet justice sounds when it’s not pretending to be entertainment.

—

Portland shrank the story into something to mention in the produce aisle and then forget by bakery. The case moved like cases move—forms, continuances, language that never once includes the sound a father makes when his son fails him.

Caroline shepherded Dad through the process. Identity theft. Unauthorized access. Jason’s lawyer stacked remorse and circumstance until the sentence resembled a scaffold: no prison, restitution, counseling, probation, the long small work of unlearning.

My mother attended each hearing, mascara migrating, hair losing the battle with weather. She looked at me as if I had rewritten gravity. You took my son, her eyes accused. Gravity was already here when I arrived.

When it was over, Dad called me into his office, the drafting table replaced by labeled banker’s boxes. “I rewrote my will,” he said without preamble. “Company, house, accounts. They pass to you. They’ll get nothing.”

A hinge caught in my throat. “Dad—”

“It’s not revenge,” he said, and even he winced at the word. “It’s structure. Maybe it’s my apology—rebar we should’ve set twenty years back.”

Within weeks, Jason liquidated his costume—car, watches, the leather sectional Mom bragged about. He and Mom rented a tired duplex at the edge of town. Marjorie reported the porch sagged in the middle.

When I drove north, Dad loaded my suitcase in a drizzle that couldn’t commit to rain and handed me an envelope like it might wriggle.

Inside: a check for eight hundred thousand dollars.

“For your future,” he said. “For what it was supposed to help you do. Build something with it that you’ll be proud to name.”

I put my hand to his cheek. He leaned into it the way tired men lean into good walls.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll build.”

—

Six months later, light ran across polished concrete floors in a narrow storefront on a street that smelled like coffee and salt. I flipped the sign to OPEN on a Tuesday. Harbor Line Studio began.

The racks stood like a thesis: jackets with seams that only reveal themselves to people who care, silk that picks up the hand, trousers that make errands look like intention. I stitched my initials on the reverse of each tag where only I would see them.

I learned the building’s respiratory system—morning hiss, afternoon clank, the night hush when the block listens to itself. I learned when to roll the mannequins toward the window. I learned how winter light eats color and how to feed it back.

Money didn’t make anything easy. It made it possible. There’s a difference. I behaved as if the check would vanish if I stopped moving.

Dad visited with coffee and that smile from photographs where I’m a small child covered in sawdust. He stood in the doorway and nodded in the rhythm builders nod when the lines are true. He didn’t mention his will again. He didn’t need to.

Marjorie declared the shop “evidence.” I think she meant proof of concept: that the good ones make something sturdy out of what the bad ones try to break. She told her friends to touch the fabric. “Good cloth wants a hand on it,” she’d say. “Same as a good story.”

From my mother, nothing. I folded the silence and shelved it—reachable but not required. Jason’s restitution checks arrived like a metronome—each a small hinge that squeaked and then settled.

Some evenings, the streetlamps outside found that same frequency as the chandelier. The hum used to mean dread. Now it sounded like a reminder: the room will hold. The room is yours.

On a Thursday, Caroline came in with her litigator’s bag and a softness she wore only with friends.

“These lines are honest,” she said, running a hand along a jacket. Then she smiled at herself. “Listen to me. Cross‑examining a hem.”

“Coffee?” I asked.

She nodded. We stood at the small counter in back, the shop smelling like dark roast and new cloth.

“Your mother reached out,” she said. “She wants a meeting. Says she wants to apologize.”

“No,” I said, and felt nothing inside me crack at the firmness of it.

“I told her you might not be ready. Or ever.”

“I’m not collecting confrontations,” I said. “I’m collecting quiet.”

Caroline’s smile was half pride, half relief. “Then you’re already on the other shore.”

She bought a navy jacket with a line that knew where it was headed. “Quarter inch at the waist,” she said from the platform. “Everything else fits.”

When she left, I stitched and thought about forgiveness as bookkeeping. It doesn’t erase debt. It just stops charging interest to your heart.

—

Summer turned the city earnest and bright. Harbor Line found its gait. Bridesmaids came in with a friend who couldn’t stand chiffon. Executives arrived alone and tried on structure they weren’t sure they’d earned. Tourists admired the window and confessed their luggage wouldn’t allow another ounce. Old men who knew tailoring from old lives patted seams with silent approval that meant more than reviews ever will.

A woman my age stopped near the tweed and talked into the air. “My brother wants to sell our grandmother’s house. My mother says I’m selfish for saying no.” She looked over at me. “Isn’t it curious how the no‑sayer is always the villain?”

“Curious,” I said. “And familiar.” She left with a dress that looked like a boundary.

Dad’s visits stretched into lunch. He sat on the stool by the register and told me stories I’d never heard—stairs that didn’t math, cedar that remembers rain, beams that lie unless you force them to tell the truth. He said the world comes down to gravity and whether you respect it.

One afternoon he set a key ring on the counter. “I keep thinking about legacy,” he said. “I put RB Bennett & Sons on the truck. Felt like speaking a future out loud. Maybe I should’ve written & Daughter.”

“You couldn’t have predicted any of this,” I said.

“I could’ve valued what was in front of me more clearly,” he answered, sliding the keys toward me. “To the shop, to the truck, to whatever you decide is or isn’t yours.”

“I don’t need the truck,” I said.

“I know,” he said, pleased. “But I like you having the option. Choice is wealth nobody can skim.”

—

The first note from my mother arrived in autumn, forwarded from the Seattle address I’d let expire. Thick cream envelope, careful handwriting trying to look like itself.

Lucy,

I am sorry I wasn’t the mother you needed. I thought I was protecting family. I was guarding a story. I miss you. I hope you’re well.

Love,

Mom

I filed it in the drawer with receipts and thread. It felt like both evidence and sentiment and I didn’t trust either yet.

Another letter. Then a postcard from Cannon Beach like we were school friends. I let them accumulate. “Sorry” is a single plank. You still have to decide whether you want to build a bridge from it.

Jason didn’t write. He mailed restitution like clockwork. When a payment was three days late, my body rehearsed the old anxiety. Caroline texted: processing delay. The money cleared. My lungs loosened. I didn’t enjoy knowing that delay could still move my chemistry around.

—

December rain stitched the air. A man stepped in, jacket freckled with water, with the look of someone who wants permission from the room.

“Can I help you?” I asked.

“Maybe,” he said, laughing at himself. “I’m failing at a gift for my sister. I’m not good at gifts.”

“Give me three things about her.”

“She’s smarter than me. She wants pockets in everything. And she never apologizes for being complicated.”

I handed him two options that felt like future heirlooms. We talked about weather and stairs and how Seattle keeps drawing new lines for itself. He was an architect named Aiden with a small firm in Belltown and a scar on his forearm that looked like a letter.

“Coffee?” he asked when he signed the slip.

“I’m trying to avoid clients,” I said.

“I’m a brother first,” he said. “And an admirer of pockets second.”

“That’s already complicated,” I said. “But okay. Twenty minutes. Bring an umbrella.”

He showed with two. He gave me the one that worked better. I should have taken that as the thesis.

We learned each other slowly—afternoon walks, cups of coffee, sometimes the quiet that says more than testimony. When I told him about the dinner and the lights and the sirens, he didn’t reach for a motivational poster. He said, “That sounds exhausting,” and let the exhaustion be real. I liked him more for that than anything else.

On New Year’s Day I stood in the shop with a yellow pad and wrote what the studio owed me and what I owed it. The ratio didn’t sing, it steadied. I mailed Dad the first repayment on the check he had forced into my hand. He called to say I didn’t owe him. I told him I owed the principle of it. He laughed and said principle was the only thing that ever made him feel rich.

In February, Mom walked into the shop. No call. No warning. She stood by the window with her hands pressed together, the posture of someone cold or reverent.

“Hi, sweetheart,” she said.

“Hi,” I said, because my childhood had given me certain defaults.

“It’s beautiful,” she said, eyes taking the place in slowly. “I’m proud of you.”

“Thank you,” I said, unsure where to put a compliment from a source that had run dry when I needed water.

“I’m doing a program,” she said. “Family counseling attached to Jason’s probation. They use the word enabling. I hated it. Now I think it might be a diagnosis.”

I kept my hands on the counter where I could watch them be steady. “What do you want from me?”

“Time,” she said. “And the chance to do a little less damage.”

“I can give the first,” I said. “The second is yours to manage.”

She nodded. “Fair.” She studied a rack and then turned back. “Do you remember sewing your Halloween costume at eight? You bled on the fabric and hid it because you thought you’d ruined it. I told you mistakes ruin things. I don’t know why I said that. You finished the dress anyway. You glowed.”

“I remember,” I said, and did not add what I had wanted to hear instead: we can wash it out.

She left without buying anything. That seemed right. Leave the air clean.

A week later Jason called. I let it go to voicemail and listened with the phone face down.

“Lucy,” he said. No bravado left. “I’m in a program. I’m sorry. I know sorry isn’t a bridge. I’m working framing with a crew boss who thinks talking is a waste unless it’s about measurements. It pays like honesty—slow and enough.”

I called Dad.

“He’s with Martinez,” Dad said, approval in the grain of his voice. “Good crew. Measure twice is law. He’ll learn or he won’t. But if money comes in slower than he used to spend it, that’s a better direction.”

“Should I call him back?” I asked.

“I want you to keep your peace intact,” Dad said.

“I don’t know what that requires yet.”

“Then leave it undecided,” he said. “Some choices need to season.”

Relief arrived like heat returning to your fingers after cold. I didn’t have to pick a gate yet. I could let the pasture be.

—

Spring threw blossoms at the sidewalks like confetti. Aiden and I walked under trees that could not help themselves. He told me about a stairwell he loved in a building nobody visited for the stairs. I told him about the doghouse roof Dad let me nail three shingles onto when I was a kid and how I checked them every day after rain to see if water had gotten smart.

“You build even when you think you’re just bracing,” he said, not as flattery but as measurement.

We kissed in the shop’s doorway one evening when the street felt like a promise. Ordinary and holy at once.

On a late Tuesday, a woman brought in a dress she’d bought two years ago. The hem had dropped. She apologized like she’d broken a vow.

“Hand it here,” I said, taking the dress the way you take a fragile thing because the care is what matters. I stitched at the counter while she watched. Ten minutes and the line ran true again.

“What do I owe you?” she asked.

“Tell me one thing you love about the person you love most that you have never said out loud.”

She did. It is not mine to write here. But the shop felt like it was doing what it was meant to do—clothes and confessions, seams and sentences, shape and shelter.

—

The second summer, Dad called from a hospital bed with bright cheer that fooled nobody. “They’re keeping me overnight to annoy me healthy,” he said.

I drove through the dark that looks like distance and found him small but anchored. A scare. Numbers the doctors didn’t like. He joked about hating gowns.

“They say it’s not the big one,” he said. “Just a memo from my heart. I don’t need the reminder more than once.”

I took his hand. “Here’s your one: you are not your company.”

He squinted like it was a sentence he had to translate. “That’s a line I wish someone had written on the wall of that garage when I started.”

Mom arrived at dawn with pastries and careful eyes. She stood on the other side of the bed and didn’t reach for me. We both reached for him.

“Hi,” she said.

“Hi,” I said.

“We’re older now,” she said, trying on a bridge.

“We are,” I said. “Let’s spend it better.”

Back home, Dad declared he would retire in phases—teach instead of lift, speak instead of haul. “The crew can shoulder the beams,” he said. “I’ll carry the levels and the words that keep beams honest.”

“Will you be bored?”

“Busy,” he said. “There’s a difference.”

On Fridays he came to the shop to fix things that did not, on the surface, require fixing. Shelves that didn’t wobble learned a deeper stillness. He taught me how to hear a building sigh and when to worry about it. He brought a broom he preferred. I let him win that one. The floor looked better.

Wednesdays, my mother began to stop by with coffee and a smallness that did not feel like performance. She would sit and read catalogs and sometimes try on a jacket and look surprised that it suited her.

“I’m learning how to be proud without bragging,” she said once.

“Bragging makes it about the bragger,” I said. “Pride points toward the work.”

“I wish I had learned that sooner.”

“Me too,” I said. “We’re here now.”

—

Three years in, we threw a modest party—more exhale than spectacle. Friends. Clients turned friends. Dad and Aunt Marjorie. Caroline in navy. Aiden with the umbrella that always worked.

Jason arrived late and stood in the doorway like a man who now asks rooms for permission. Drywall dust on his sleeves looked better on him than any of his watches ever had.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” I answered.

He handed me a small box. Inside was a seam ripper with a handle carved from warm, simple wood.

“I made the handle,” he said, and then grinned at himself. “Okay, I whittled it. Martinez says if your hands aren’t on a tool, your brain gets slippery.”

“It’s beautiful,” I said. It fit my palm like it knew me.

He didn’t request forgiveness. I didn’t grant it. We stood by the window and let the room be a room. He told me about framing a staircase without anyone redoing his numbers. I told him about a client who cried because a jacket fit the way she wanted her life to fit.

When he left, nothing had been forced or taken. That was new.

Dad lifted a glass. “To work that holds,” he said. “To lines that tell the truth. To daughters who teach their fathers to retire properly.”

Laughter carried easy. I looked at the three people who had hurt and tried to love me, sometimes inside the same hour, and realized something I hadn’t allowed before: family is not an account payable. It’s a ledger you either balance with honesty or you close.

After midnight, we went dark. The shop turned to outlines and quiet. I laid the seam ripper on the counter. Aiden slipped his arms around me from behind and rested his chin on my shoulder.

“You built this,” he said into my hair.

“With help,” I said.

We stood in the city’s hum until the air suggested bed.

—

There are nights I still wake to an electric buzz in a room with no chandelier. Memory ignores addresses. I list what I know until my body agrees: the names of fabrics and tools, stair math, the weight of a father’s apology, the sound of a brother learning to measure twice and cut once.

Sometimes at two in the morning I answer messages from women who sign only a first name. They write about dinners where they had to defend themselves to the people who taught them where to put the forks. They write about signatures and accounts and the way money can be a weapon or a balm. I don’t give advice. I tell them what I told myself after the sirens: you are allowed to protect what you made. You can choose quiet over spectacle. Justice is calibration, not volume.

On a clear Sunday, Dad and I drive to Sauvie Island with thermos coffee to look at a renovation he’s consulting on. He talks about wood like other people talk about love. He shows a young crew chief how to run a string line so the world obeys it. I watch and understand that the same man who asked me where the money went also taught me how to find the answer.

Driving back he says, “You were right. You protected it.”

“Protected what?” I ask.

“Your money. Your name. Your life,” he says. “I would’ve called it stubborn once. Now I call it respect for the load‑bearing wall.” He smiles at the road. “I’m proud of you, Lucy.”

“I know,” I say, and being able to say that without crying fills the car with a music I recognize now.

At night I lock the studio and walk home with the sense that the city is doing the same—locking what should be kept, leaving windows lit for what needs to find its way back. Some doors will open again. Others will not. Both choices can be holy.

On the counter I keep a small wooden box. Inside: my grandmother’s thimble, Jason’s carved seam ripper, a printout of the transfer timestamp from that dinner night, and a Polaroid of Dad under a beam grinning like he invented shade. It’s not a shrine. It’s a toolkit. On hard days, I open it. On good days, I forget it’s there.

The shop breathes. The block breathes. I do the day’s work. Measure twice. Cut once. Press a seam and run my thumb along it until it lies straight and admits what it is.

When the old hum returns, I answer it with the sound of my door unlocking in the morning and the first bell as someone walks in—bright, ordinary proof that I am here, the work is ready, and we can begin again.