I was thirty-five, a marketing manager in Lincoln, Nebraska, with a condo whose mortgage smelled faintly of coffee and ambition. I’d bought it with presentations approved at midnight, with breath the color of burnt espresso and slides rewritten until the kerning behaved. My place was four rooms and a balcony that caught the afternoon sun like an old friend. I knew the stubbornness of my dishwasher and the exact creak of the hinge on the hallway closet. The building sat on a quiet street where the American flag on the corner house snapped in the wind like a steady metronome. It was home because I’d chosen it, because I’d paid for it, because no one else had paid a cent.

On a Monday, during standup, my phone buzzed against the conference table—a tiny siren slicing through budget talk and Q4 projections. We were swaddled in the tidy language of KPI and CPA and “what’s our CAC on that?” when the screen lit with a name I knew too well.

TESSA: Need $2,800 for prom. Send now.

My jaw locked. $2,800 for a dress, a limo, a night of selfies that would evaporate by morning. A number with my name attached by habit. My manager kept speaking about a creative refresh while my heart performed its own. I slid the phone into the angle of my lap beneath the table, thumb hovering.

ME: Earn it yourself.

The room continued, unaware. We marched through agenda bullets, the careful choreography of corporate time. I kept my face calm, my spine straight. Five minutes later the follow‑ups arrived—the kind of follow‑ups that carry a family name like a signature you don’t remember learning to write.

Diane: Pay or don’t call yourself family.

Carl: Do the right thing.

The sentences landed like a memory of winter—sharp, uninvited, a cold that knows every window. Heat raced up my neck. For years I’d wired money to a joint account I’d opened so we wouldn’t have to have this conversation every holiday, every emergency, every can you help. Bills, groceries, the basics, I told myself. The responsible thing. The adult daughter thing. Emergencies.

But there it was: satin rebranded as survival. Rhinestones as morality. A $2,800 ultimatum served on my lunch hour.

I kept my hands folded on the table, nodded at the right spots, assigned action items. I walked back to my desk with the unhurried gait of someone who has decided not to bleed in public. The office smelled of printer ink and hand sanitizer, the seasonless scent of modern work. I opened an email about a digital out‑of‑home pilot, answered a question about a landing page, approved a spend that had been negotiated down to the bone. Then I put my phone face down and watched my reflection blur in the glass until the glass was just glass again.

That night, I paced the length of my living room until the carpet felt thinner. The balcony door rattled a little in the March wind. I turned on the lamp with the linen shade, the one that made everything look like it belonged to a calmer person. I scrolled through bank transfers: $1,200 here, $800 there. A string of kindnesses I had labeled duty. I remembered Tessa’s birthday parties that shimmered while I worked weekends. Diane’s quick excuses, Carl’s quiet just this once. I remembered how the joint account had felt like a solution—anonymous, efficient, no awkward handoff of cash in a kitchen where the coffee machine sputtered like an argument. They had a debit card attached to it. I had the responsibility attached to it.

At midnight, I stood over my laptop with the same steadiness I use to approve a campaign. I opened tabs with surgical calm. I found the utilities I covered, the streaming services, the subscriptions that crowded the edges of a month like dandelions. I said the words in my head before I clicked, like a liturgy I finally understood.

Cancel.

Cancel.

Cancel everything.

I shut off the automatic transfers. I revoked cards that had my name embedded in their plastic smile. I changed passwords. I set new alerts. The joint account stayed open because there were legitimate bills winding through it like vines through a fence, but my faucet was off. The sound in the room changed—a silence like after a storm when the last raindrop hits and your body, which has been braced for thunder, realizes thunder is over.

By 8:30 the next morning, my world felt tilted and eerily quiet. The office was in that pre‑meeting hum where everyone is pretending not to sprint. I took a sip of coffee that tasted like resolve. Then an email from the bank flashed urgent.

Large transaction alert.

My stomach dropped. It wasn’t about prom anymore. It had never been about prom. It was about a pattern I had been careful not to name. The figure glared up at me: $5,000 out of the joint account at dawn. Rent money for them or another whim. Either way, it had my signature on it whether or not I’d touched a keyboard.

I needed facts, not guilt. I walked two doors down to Legal and knocked on Ellen Ward’s office. She’d left for law school years ago and come back with a spine like polished steel and a calm that looked like mercy.

“Quick favor?” I asked, and my voice didn’t tremble.

“Sure,” she said, sliding off her reading glasses. “Come in.”

Minutes later, with my credentials and her brisk competence, we were inside the bank portal. The ledger didn’t care about the stories I told myself. It didn’t care about birthdays or winter coats or the kind of panic that rewrites a budget in December. It told a story my memory had tried to redact.

Months of large transfers to card issuers, auto finance, a lender I didn’t recognize. Then the smaller taps—boutiques I’d never stepped inside, restaurants with linen napkins, a travel agency, and unbelievably, a prom planner.

Ellen scrolled, her brow knitting. “This isn’t groceries.”

“No,” I said, and the word sounded like a door closing. “They’re servicing debt and lifestyle.”

We pulled statements by year. We sorted. We added. The total landed like a wind that knocks the breath out of you and leaves you staring at the sky as if the answer is written there. One hundred thousand dollars withdrawn since I opened the account. A second mortgage surfaced in the logs like a submerged shape you always knew was under there.

I closed my eyes, then the faucet—properly this time. I called the bank and froze transfers, revoked cards, escalated alerts. I didn’t cry. I didn’t apologize to the stranger in fraud prevention who said “I’m sorry this is happening” as if he had been invited into our kitchen in Lincoln and watched me hand over my twenties like napkins.

Then I wrote one careful email to the three people who had taught me that love was both noun and invoice. The account is closed to you. I know about the withdrawals. There will be no more money.

Phones detonated. Tessa first, outraged and breathless. You can’t do this.

“For what?” I asked. “Another dress?” I didn’t have to raise my voice. She hung up with a sound like fabric tearing.

Diane texted paragraphs about survival, about how we take care of our own, about how she had done everything for me. Carl sent a single line: Think about what you’re doing to us.

I did. Then I chose myself.

I printed everything. Tomorrow I would bring the statements to their house. I didn’t want to leave a bind of PDFs that could be ignored. I wanted paper. I wanted the weight of it in my bag. I wanted the sound a stack of pages makes when you place it on a coffee table.

I drove to their split‑level at noon with a manila folder under my arm and the brittle calm of a sleepless night. The neighborhood was a brochure for American ordinary—maples just starting to fuzz green, a basketball hoop with a net that had seen two winters too many, a grill cover flapping like a loose thought. The screen door at my parents’ place still had the small tear near the handle from a summer years ago when Tessa slammed it with a teenage fury that melted the hinge screws.

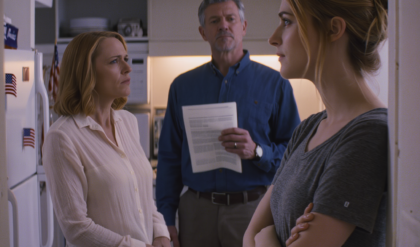

Diane was on the couch. Carl hovered by the window as if guarding a horizon only he could see. Tessa scrolled on her phone, her nails perfect little moons.

I laid the statements on the coffee table with a care I used for fragile things. “I know about the second mortgage,” I said. “About the cards. About the prom planner.”

Diane’s mouth pinched, the same pinched shape it took in grocery store checkout lines when she thought the person ahead of us was making a scene. “You don’t air family business.”

“You made it my business when you spent my income,” I answered.

Carl bristled. “We were drowning. You were supposed to help.”

“I did help,” I said, tapping the totals. “A hundred thousand dollars. That was for necessities. You used it to postpone consequences and pad Tessa in silk.”

Tessa finally looked up, cheeks hot. “I didn’t ask you to open that account.”

“You asked for $2,800 and called it love,” I said. “Love is not a wire transfer.”

Voices rose, then broke. They demanded, defended, deflected. The scripts we all knew by heart. I didn’t shout back. My tone stayed level, a steady line on a heart monitor. I gathered the pages and stood.

“Here’s the boundary,” I said. “No more money. If you want my presence, it has to be without invoices.”

Diane blinked. She did not say I’m sorry. Carl said, “Then we’re finished.”

I nodded. “If that’s your choice.”

I walked to the door. The sunlight outside looked the same as when I arrived, which felt like disrespect. I left, blocked numbers in the driveway, and sat with the engine off until my pulse released its grip.

Weeks passed in the orderly chaos of spring. A cousin texted me on a Tuesday: Bankruptcy filed. House listed. Tessa took a retail job. The words sat on my screen like groceries on a belt—ordinary, transactional, paid for in cash you can count. I felt grief and oxygen in equal measures. The grief did not ask for a refund. The oxygen did not apologize.

I met with Ellen again. We closed every loophole. We built a budget that had my future in the center and nobody else’s wish list taped to the bottom. Therapy helped me unhook guilt from duty, love from invoice, daughter from donor. On Saturdays, I learned the shape of a morning that belonged to me. I learned that a cart with only my groceries in it is not a selfish act. It is a grocery cart.

When the trees along O Street filled in and the corner house flag hung lazy in warm air, I carried a gown I once bought for a gala—the kind of evening where you laugh too loud because you don’t know what else to do—to a thrift store. A girl choosing thrift twirled in it, laughing. The hem lifted like it remembered. She asked the clerk if it was too much. The clerk said, “It’s perfect.”

That joy—that was the right ledger entry.

The Monday began the way Mondays begin in offices across the Midwest: coffee that tries to be a promise, people in navy blazers negotiating the borders of a week. The standup lived in the small glass room with the flickering light and the plant everyone assumed someone else watered. Our head of media was advocating for a spend shift; creative wanted two more days; finance looked pained in the way finance looks when numbers don’t act like pets.

My phone vibrated with the kind of insistence I used to confuse with urgency. The screen glowed like a small stage. Need $2,800 for prom. Send now. Tessa’s certainty rode the words like a crown, like the universe owed her a limo and a spray of rhinestones across a sweetheart neckline because people with eyelashes like hers don’t take Uber.

I’d been the one to make things possible since I was twenty‑two and said sure in a kitchen where the refrigerator hum was the loudest thing, said of course to mortgage interest because the bank phrases it soft, said I got it with a laugh that was supposed to make it feel lighter. I’ve been the one to make emergency feel like Monday. When my parents said we’re short I could hear the months stacked like boxes with December circled in red and it never occurred to me to ask who wrote the calendar.

People love a daughter they can convert into a plan. They love her steady, her quiet wire transfers, her holiday gifts that double as grocery money.

I never wanted to be a plan again.

So I typed Earn it yourself under the table and pressed send as the head of media said, “We’ll A/B test the hero image.” I looked up and nodded like I’d said the thing in a meeting where the thing is always almost said and then tabled until next sprint.

Diane’s text—Pay or don’t call yourself family—arrived in two sharp bites. Carl followed with Do the right thing, and somewhere deep in me a lock I’d been carrying around since childhood clicked like a good door finally closing.

At home that night I opened my laptop and navigated to the places where obligation lives. Nothing in the UI tells you what it will cost you to keep helping people who won’t help themselves. There’s no pop‑up that says Are you sure? in a voice that sounds like your grandmother, the one who kept a coffee can of cash in the pantry and would have told you, Baby, generosity without honesty is just an expensive story.

I canceled the cable package I’d upgraded three Christmases ago when Tessa wanted more movie channels “for family night,” which played once and then dissolved. I canceled a gym membership no one had used since the second week of January last year, a Peloton app I’d never logged into but had been paying for on a card with my name. I canceled subscriptions to things that send you little boxes of hope. I set text alerts for any transaction over $100 and email alerts for everything else.

The sound I made when I clicked the last Confirm was small and fierce.

On Tuesday morning, the alert. The $5,000. The way my pulse went from a tap to a siren. The knowledge that money had left while I was sleeping, that sunrise had been greeted with a transfer I had not authorized, that my name had been used like a key by hands that didn’t have to ask.

Ellen didn’t ask why I came to her. She turned the monitor so we could both see. She typed in the bank portal URL, waited for the two‑factor code to ping my phone, nodded when I handed it over. We navigated through the ledger like walking a neighborhood you used to love and now see with an appraiser’s eye.

There are numbers and then there are numbers you remember like birthdays. I will always remember $100,000. I will always remember the second mortgage I hadn’t co‑signed and hadn’t known about, hiding in the line items like a quiet betrayal.

“I’m sorry,” Ellen said finally, and I believed her. There are apologies that are gauze and there are apologies that are a hand steadying your elbow as you step off a curb you misjudged.

“Don’t be,” I said. “This is information.”

We made a list of what to shut down. I called the bank, and the fraud department person was kind in the way people are kind when they’ve had to learn how to be kind in order to keep their own heart from rusting. I froze the transfers. I revoked cards. I reset passwords to phrases only I would know: not the street I grew up on but the street I intend to. Not my first pet but the plant I haven’t killed yet. I wrote the email to Diane and Carl and Tessa with the factual tone that says a door is no longer a door, it is a wall.

Then I printed. Stacks and stacks. I held the numbers and felt their heft.

At my parents’ house, the air was too warm in that way of houses that prefer comfort to clarity. Diane had the remote in her hand like a scepter. Carl’s arms were crossed, which is to say his heart was. Tessa’s phone was a mirror she liked better than any room.

I placed the pages on the table like a meal.

Tessa was the first to speak when it became clear I was not there to negotiate. “You’re dramatic,” she said, when my voice was level. “You always make things a big deal.”

“A second mortgage is a big deal,” I said, and watched the way her face flickered when she didn’t like the math.

Carl’s we were drowning was a sentence I had known before he said it. “Then you learn to swim,” I replied. “You don’t tie your daughter to the lifeboat and tell her to kick harder.”

We circled the same arguments we’d circled for years, only this time I didn’t let the merry‑go‑round spin. I didn’t accept the ticket. I stood beside it and named the music as noise.

When I said boundary out loud, the word felt like a new piece of furniture I would keep, something with clean lines and no fake brass.

In the driveway afterward, I blocked the numbers and stared at my hands on the steering wheel until I liked the way they looked—capable, steady, mine.

There’s a grief that doesn’t sob. It sits in a chair and exhales and watches the sun move across a wall. It lets you do the dishes. It lets you answer emails. It doesn’t require a song. It just asks you to keep choosing.

In April, my cousin’s text about Bankruptcy filed. House listed. Tessa took a retail job arrived between a meeting invite and a coupon I didn’t want. I read it twice and felt the complicated symmetry of consequences that finally found their owners. I did not write I told you so. I did not write anything at all. I put my phone face down and watered the plant I hadn’t killed yet.

Ellen and I met again and built a budget like a house with a foundation that belonged to me. She said, “Put your future at the center,” and I did in a spreadsheet that made more sense than any group text ever had. I created an emergency fund with my name on it, not a family fund disguised as responsibility. I learned the gentle terror of looking at a number that exists because you allowed it to.

Therapy unhooked the Velcro that kept guilt stuck to love. We talked about enmeshment and obligation and how a little girl who learns to be useful becomes a woman who confuses usefulness with worth. We talked about the difference between a no that hurts and a no that heals. We talked about how to be a daughter without being a donor.

On the Saturday of the thrift store dress, I watched a girl spin in a mirror and thought about the ways joy can still find you after you’ve stopped paying for everyone else’s. She asked if the dress felt like too much. I shook my head. “It feels like exactly enough.”

Outside, the flag on the corner house moved in a breeze that smelled like cut grass. I went home to my balcony and the crooked hinge and a grocery cart that had only my dinner in it. I ate at my table without a spreadsheet open. I breathed. The air felt paid for.

And when my phone lit up on the table that night, I didn’t flinch. It was an alert I’d set for myself: You made the right choice. Not from a bank. Not from Diane. Not from Carl. From me.

I didn’t press Cancel on that.

I didn’t sleep much after I set my own alert. The condo had the steady hush of a hotel at 2 a.m., that in‑between quiet where the city seems to hold its breath. I lay there and listened to the radiator whisper and the elevator cables hum three floors over. I counted the choices I’d made the way you count steps to the kitchen in the dark: slow, cautious, learning the corners of a room you thought you knew.

Morning rinsed the windows in pale light. I made coffee the way I always do—two scoops too strong—and stood barefoot on the kitchen tile until the cup warmed my hands enough to feel like courage. Outside, a pickup rattled past with a bed full of lumber and the American flag at the corner house tugged at its pole. The world continued, which felt like both insult and blessing. I watched the steam braid up from my mug and didn’t check my phone.

At the office, people talked about weekend errands and the best route across town when a train stalls the crossing. Nebraska conversations—the soft, practical kind that weigh time like grain. I opened my laptop and slid into the day’s sequences: a deck about a summer campaign, a string of emails that wanted a decision but did not want the responsibility for it. My inbox recognized the new quiet; it did not soften because of it.

Two doors down, Legal’s lights were already on. Ellen kept early hours like people who learned somewhere that clarity comes if you meet it at the door. She waved me in without surprise. We didn’t redo yesterday. We refined it. We listed every place my name touched theirs. We shut valves and locked gates and left notes for my future self.

“Paper is proof,” she said, not as sermon but as fact, as if the universe had been written on ledger paper and only later translated into everything else.

On my break, I walked the block—past the bakery that proves butter is a language, past the green newspaper box that refuses to die. Lincoln feels like it’s always five minutes from a parade. Even on ordinary Tuesdays, there’s a readiness for a marching band to turn a corner. I let that feeling walk beside me and didn’t try to rename it hope.

Back at my desk, I opened a blank document and typed three words I hadn’t given myself in a long time: What I want. I didn’t make a vision board. I made a list that could stand a Kansas wind.

-

- Sleep without bracing for a phone to detonate my heart.

-

- A savings account that belongs to me and an emergency fund that is not a family plan in disguise.

-

- Holidays where my presence is a gift and not a currency.

-

- The capacity to say

no

- without a follow‑up paragraph explaining why I still love you.

I added one more and felt both foolish and brave: A life where quiet doesn’t mean danger.

I saved the file in a folder called Personal and, for the first time, the word didn’t feel like a thing I had to apologize for.

The cousin’s text about bankruptcy came on a Wednesday between a calendar invite and a shipping confirmation for a pair of shoes I’d bought with my own money and my own taste. House listed. Tessa took a retail job. The words were flat and unadorned, the way official language always is. I read them again and pressed my palm to the desk—wood laminate, warm where the sun pooled.

I didn’t want vindication. I wanted clean air.

At lunch I took my sandwich to the break room because there’s something honest about eating at a table that dozens of lives touch every day. The fridge hummed like a large, content animal. Someone had left a Post‑it on the microwave: Please cover your soup. The tiny plea of shared space. I felt, suddenly, that my life could fit into its edges without spilling.

In the weeks that followed, I practiced not answering. The urge came like a reflex, the body trying to throw itself between a sound and its meaning. My thumb hovered over icons that used to be family. I let it hover and then lowered my hand and drank water. I went to bed when I was tired and not when my sense of usefulness had finally exhausted itself.

I didn’t drive past the house with the For Sale sign. I could have. Lincoln is small enough that you can ghost your own history and still bump into it at a red light. I decided I didn’t need to see the windows I’d grown up behind. Information and injury are not the same thing, even when they pretend to be.

Ellen and I met again. We built a budget that looked like a floor plan. Category by category we sketched out rooms I could live in: mortgage, utilities, groceries that belonged to my fridge and not to anyone else’s pantry. We penciled in a line for generosity and another for no. We gave both permission to exist.

Ellen’s pencil made a satisfied sound when numbers reconciled. She didn’t say proud of you because we don’t say that to adults in offices; we say nice work and you’ve got this and looks solid. But the room was warm and I didn’t feel alone, which is its own kind of compliment.

I reread the bank statements with a new eye, the way you reread a book you loved as a teenager and discover the plot had been telling you its truth all along. $1,200 here, $800 there, holiday weeks fat with purchases that called themselves necessary because the calendar was watching. A second mortgage I had not signed for, nestled among the samplings of treats and temporary fixes. I highlighted nothing. I understood everything.

On Saturdays I learned that quiet has textures. There is the quiet of punishment—the kind that follows slammed doors and withheld affection. There is the quiet of absence, where you wait and wait for a call that does not come and you feel small enough to slide under a rug. And then there is the quiet of a room that belongs to you, where the refrigerator hum is just a hum, where the silence is not a test but an environment. I sat in that quiet and didn’t grade myself.

Therapy didn’t look like revelation. It looked like writing down sentences and crossing out the ones that were lies. I didn’t add the therapist’s name to my story. I didn’t need to. What mattered was the way I began to recognize the thin whine of obligation masquerading as love. I practiced saying I can’t and then not following it with because. I practiced saying no and letting the period be period enough.

At night, I made dinner that did not require a spreadsheet. Eggs and toast can be a feast if you eat them at your own table. I put my phone in a drawer and listened to a podcast about people who restore old houses. They talk about joists and rot and the miracle of finding original hardwood under vinyl. They talk about choices that feel small and aren’t. They talk about integrity and how water will always find the crack if you don’t seal it. I wrote Integrity is waterproofing on a sticky note and put it on the freezer door.

The thrift store dress lived in my closet for a week before I let it go. I took it down from the hanger and laid it on the bed. The fabric was cool and expensive under my hands, the color somewhere between black and the night sky above a cornfield when there’s no moon. I had bought it for a gala three years ago because that’s what you do when your career brushes shoulders with the kind of people who talk about giving back while their assistants arrange the giving.

At the store, the bell above the door announced me with a cheerful clatter. The aisles smelled like dryer sheets and a hundred different lives. A clerk with a barcode scanner looked up and smiled the way Midwestern clerks smile, like they know every story is the same story told with different labels.

“Donation?” she asked.

“Donation,” I said, and set the box on the counter.

The girl trying on the dress wasn’t a coincidence I invented to comfort myself. She was real as the mirror, with a braid like a rope and a face that had learned recently that it could be beautiful. She stepped out of the fitting room and the dress caught the fluorescent light like it was a better kind of star. She twirled once and laughed, not the brittle laugh of someone asking for permission, but the light laugh of someone receiving it.

“Too much?” she asked the clerk, palms lifted.

“It’s perfect,” the clerk said, and the word felt earned.

I stood there in my jeans and sweater and thought, Yes. Let it be perfect. Let something land on the right person without me funding, arranging, apologizing for it. Let joy be a ledger entry that doesn’t need my signature.

On the drive home, the wind pushed the car around a little and the sky did that big Midwestern thing where it looks close enough to touch. I breathed with it and let my shoulders go heavy. A few blocks from my building, the same flag lifted at the corner house and lay down again, like a chest rising and falling. I parked. I went upstairs. I put the receipt in a folder labeled Charitable. The word finally meant something that didn’t hurt.

I didn’t check social media for prom photos. That would have been a new kind of paying, and I was done inventing currencies.

One evening I opened the manila folder again—the one that had lived under my arm when I walked into the split‑level and laid paper on the coffee table. I stacked the statements in chronological order and slid them into sheet protectors because order is a kindness, even to yourself. I noted where the second mortgage began, where the spending swelled, where the $5,000 left at dawn like a secret that doesn’t know it isn’t one. I added a cover page that said Closed and Do Not Reopen and placed the binder on the highest shelf in my hall closet. The act felt ceremonial without being dramatic. Some stories need altars. Some only need good shelving.

Work did what work does when you bring your whole self to it—it met me where I was and asked for the best of me. I wrote lines that held up under scrutiny. I said no to a campaign direction that would have cost more than it would have earned. I said yes to a junior copywriter’s pitch with a spine. I remembered that competence isn’t a currency to spend on family peace; it’s a tool you get to use on your own life.

Ellen popped her head into my doorway one afternoon. “We’re good,” she said. “All the loose ends are… not loose.”

“Thank you,” I said. It felt insufficient for the way her steadiness had given mine a place to lean, but she knew. Grown women don’t always say the big thing; sometimes we send the right document at the right time and that’s the same as a hug.

When bills came, they were mine. Utilities, mortgage, groceries. The digits lined up and I paid them with a calm hand. Money in, money out. No covert routes through joint places. No tremor in my throat when I clicked Submit. I started an automatic transfer to my savings account—not a hidden pipeline to someone else’s crisis, but a predictable, visible bridge to my own future. Watching the number grow was not an act of hoarding or an indictment of my family. It was, simply, math.

In therapy, I learned to replace should with want and then to hold my ground when the answer to want was rest. I wrote sentences: I was convenient, not cherished. Then I wrote a final period and underlined not cherished twice, because naming the difference is a kind of architecting. If you can name the rooms, you can decide what furniture goes where.

Sometimes guilt came back in the night dressed as responsibility. It asked me to remember Christmases, birthdays, the way Diane lined up ornaments on the tree as if they were arguments. It asked me to remember Carl on the porch, eyes following weather the way men follow weather when they can’t talk about other storms. I let the pictures come, because telling yourself not to think of something is like handing your brain a to‑do list titled Think About This. I let them come and I did not let them vote.

A month out, the silence had changed shape. It wasn’t the jagged absence after an argument. It wasn’t the punished quiet of a house that wants you to notice your own breathing. It was the ordinary quiet of a Tuesday night with a book face‑down on the arm of the couch and the dishwasher grumbling in contentment. When my phone lit up on the table, it was emails about work, a shipping notice for coffee, an alert from my bank that my own automatic transfer had gone through. The number slid from checking into savings like a small boat gliding into a safe harbor. I watched it and felt no ache.

I measured time differently. Not in crises averted or exhaustion accumulated, but in the stubborn loops of a running route that belonged to me, in the thickness of library hardcovers I could now finish because I didn’t spend weekends repairing other people’s choices. I bought a second set of sheets like a person who expects to be here for a while. Stability isn’t glamorous, but it shines in the dryer light.

On a Sunday, I deep‑cleaned the condo the way you clean when a house is a body you’re learning to love again. I washed baseboards and wiped the tops of door frames. I emptied the junk drawer and threw away keys to places I no longer unlocked. I found an old postcard from a trip I took years ago and taped it inside a cabinet—nothing dramatic, just a picture of a highway slicing through a state I’d driven across alone and felt fine. Under it, in pen: You can be the person you are when no one is asking you for money.

I didn’t send it to anyone. I didn’t post it. I put a bag of donation clothes by the door. I made tea. I let the house smell like lemon cleaner and something warm and unnamed.

The next time I needed to say no, I did it in one line: I can’t do that. I did not add right now or because or I wish I could or maybe next month. I didn’t check the read receipt or watch the typing bubbles. I closed the app and opened my budget spreadsheet; the cells waited, patient and finite. There is a comfort in numbers that don’t lie, in columns that add up, in totals that reflect choices instead of needs disguised as entitlement. I balanced the month and the peace that followed didn’t ask me for anything.

Spring deepened. The maples leafed out like hands. The flag at the corner house rested more than it fought. I bought basil and thyme for the balcony and didn’t Google how to keep them alive; I read the little plastic tags and decided to learn from attention instead of fear. When the wind rattled the old hinge on the balcony door, I heard only weather.

I kept the binder labeled Closed on the shelf. I kept the thrift store receipt in its folder. I kept the budget as a live document. I kept my alert, the one that lights my phone with the sentence I didn’t know I needed to read.

You made the right choice.

On the days when grief walked in unannounced and rearranged my furniture, I read it again. I let it be true, even if only for the length of a breath. That was long enough. Truth doesn’t need to hold for a lifetime to be useful; sometimes it only needs to hold for the next decision.

I know there are people who will read this and think cold. People who will say I left them to drown, that I mistook boundaries for betrayal, that I should have given until my own mortgage bent under the weight of their emergencies. Those people have never opened a bank portal with a colleague and watched their history turn into arithmetic. Those people have never stood in a split‑level living room while a daughter calls demand love and a mother calls secrecy protection. Those people do not know what it is to be a plan with a name.

I know what it is. I was that plan for a long time. I know the pride that sneaks into usefulness, the false holiness of sacrifice. I know how good it feels to be the steady one, the one who can fix it. I also know what the mirror looks like when you finally turn on the overhead light.

This is not the version of family the movies sell. There are no speeches over pot roast. No orchestras swell under apologies. There is email, and there are statements, and there is the soft machine of a printer sliding truth into the tray one sheet at a time. There is a driveway where you block numbers and put your forehead to your steering wheel and choose to breathe anyway. There is a Tuesday where you buy basil and learn its thirst patterns. There is a thrift store where a girl laughs in a dress that used to be yours and you feel something unclench.

If the story has a moral, it’s smaller than the big words we like to embroider on pillows. It is this: love is not a wire transfer. And a boundary is not a threat; it is a doorframe. You can still wave through it. You can still speak through it. You can even open it, if the person on the other side learns how to knock.

Until then, I keep my ledger. I keep my balcony herbs watered. I keep the door hinge oiled. I keep my alerts on.

And every time the screen lights up with my own sentence, I let it be both permission and proof.

You made the right choice.

I kept the sentence on my lock screen—You made the right choice—and discovered something practical about truth: it behaves like a tool if you hold it correctly. Not a weapon, not a prayer, a tool. It tightens loose bolts. It cuts old rope. It makes a straight line where one is needed and refuses to negotiate with the parts of you that want to curve back toward an old pattern just because the curve is familiar.

Spring unspooled into a generous Midwestern summer. Lincoln smells like mown grass and sun‑warmed asphalt in June, like lake water drying on your skin, like lemonade that someone actually squeezed. I learned the rhythm of my neighborhood anew: the couple on the third floor who argue in kind tones and return their grocery cart; the mail carrier who hums; the kid with the skateboard and an air of apology who never quite sticks the landing but keeps trying. Ordinary, ordinary, ordinary—a word I had learned to disrespect and now wanted to defend. There is a holiness to the mundane when it isn’t held together by someone else’s emergency.

I made lists for my own life the way I once made lists for a family that thought love was logistics. Not the lists that become shackles—just the kind that turn spinning into going. I wrote grocery, laundry, call the dentist, oil the balcony hinge, pay the gas bill, pay yourself. I put pay yourself in bold. I began to like the way it looked there, important without apology.

At work, Q3 came into view like a train you can hear before you see. I sharpened the deck for a regional campaign that would run across billboards and side‑of‑bus wraps and in the pockets of people who don’t believe they ever asked to be advertised to. A junior copywriter with voracious eyes brought me lines worth protecting, and I protected them. We won small battles inside rooms where the air conditioning is always an argument. I remembered that this was a part of me untouched by my family’s ledger—that my competence wasn’t a dam they could open and close by text.

Ellen stopped by my office with a stack of folders, precise in her practicality. “One more thing,” she said, and slid a document across my desk. “I drafted a letter for your bank—clean language to confirm access changes and an instruction that no one can reverse them without you in person. Not strictly necessary, but it shuts a door that sometimes blows open.”

I read it and felt that little loosening behind my ribs. “Thank you.”

“Paper is proof,” she said again, and I could hear the echo of my own voice in hers: tools, not prayers.

In therapy, I learned the difference between peaceful and pleasing. Pleasing is a costume with a zipper you can’t reach by yourself. Peaceful is jeans that fit. I practiced sitting in silence and not reaching for my phone to make sure the silence wasn’t a trap. I wrote sentences that had weight: I am not an account. I am not a rescue plan. I am not a series of payments disguised as love. My therapist did not nod like a movie therapist. She waited. She knew what to wait for. She asked the question that lets a truth unstick: “What would change if you believed that every time?”

“I’d have time,” I said, and discovered I meant it.

Time behaves differently when it’s yours. It stretches in directions you forgot it could. I cooked without rushing, not much but enough: chicken in a cast‑iron skillet, tomatoes that tasted like July, corn shaved from the cob with a knife that finally remembered its edge. I ate on the balcony while late light sat heavy on the rooftops. The basil drank exactly as much as I offered it and no more. I smiled into the quiet and did not wonder what Tessa was doing. Not because I didn’t care about any human named Tessa in the world, but because caring is not the same as funding.

The joint account binder sat on my top shelf like a closed book in a house where every other book stays open. I didn’t touch it. Closure is sometimes action; sometimes it’s restraint. I kept the folder because I respected records; I left it alone because I respected myself.

One Saturday in late June, I drove to the car wash with quarters in the cup holder and the kind of errand‑light heart I used to think other people were born with. The air smelled like soap that believed in itself. I vacuumed grit from the floor mats and found a penny flattened on the railroad tracks years ago, thin as a decision. I put it back in the cup holder. Not everything sentimental has to go.

On the way home I stopped for groceries and did not buy a second cart for someone else’s pantry. I stood at the cereal aisle and realized I no longer stocked flavors I hated “for guests.” I bought the kind I like and a box of something ridiculous because budgeting has room for delight when it isn’t set on fire monthly. At the checkout, the total matched my mental math and I felt that sharp little click of character aligning with choice.

The text from my cousin came midweek. Court notice posted. Bankruptcy moving forward. House listed still. A weather report for a climate I’d stepped out of. I read it. I did not reply. I did not reroute my day to carry the weight of their consequences. I walked to a meeting with my notebook open to a page that said What I want and added another bullet: gentle mornings. I didn’t define it. I didn’t need to. My body would know when it found one.

At night, the old reflexes sometimes woke up like muscles spasming in sleep. I reached for my phone and stopped. I breathed and named items in the room: lamp, book, plant, soft thrum of the building, my own inhale. I told my nervous system we were home. Eventually, even nerves get bored of alarms that don’t ring; they learn the room.

I learned other rooms. The library, with its civic hum and its ritual of reentering the world with more than you brought. The running trail near the park, where I became a slow person who nevertheless kept going. The farmer’s market, where cash felt like participation and not like loss. I learned my town in ways that did not position me as a solution. I learned how to be the kind of adult who belongs in a place without being in charge of it.

In July, the office whirred with the kind of heat that makes computers sulk. I presented a campaign. The room’s fluorescent light tried to flatten us and we refused. The slides carried clean sentences across to people who are paid to find holes. There were fewer holes than usual because clarity has a way of traveling. Afterward I sat alone and let the hum recede. I wanted to call someone and say, I did a good job today. I wanted that someone to say, I know. I texted myself the sentence instead and laughed at the absurdity and the accuracy of it. There are worse things than being your own reliable narrator.

On a Tuesday, I ran into a woman from high school at the grocery store. She said, “How are your folks?” the way people say it when they remember the template more than the details. I said, “We’re not in close contact,” and then I did not explain. I put a box of pasta in my cart. We nodded to each other like adults in a scene that did not require exposition. I went home and wrote I am allowed to be brief on a scrap of paper and stuck it under a magnet on the fridge.

The days arranged themselves into a life. Work, runs, books, food that tasted like food, the basil thriving, the thyme struggling and then deciding to live. I bought a small fan for the bedroom and put it on a timer like a person who believes she’ll be here tomorrow. I slept beneath the murmur, a human without pending emergencies. The lock screen lit with bills I had arranged and a savings transfer I had scheduled and the sentence I had gifted myself.

You made the right choice.

August asked me if I wanted to keep going like this, and I said yes. The answer surprised me only because I’d been trained to expect that relief is temporary, that reprieve is rented, that peace has a checkout time. But here I was: the bank balance an honest number, the calendar full but not hostile, the phone mostly quiet. I checked my alerts. Nothing concerning. My life felt like the inside of a well‑packed suitcase: everything necessary, nothing crammed in rage.

Sometimes I pictured Diane’s living room with fresh boxes and stamped forms. Not because I wanted to gloat but because grief watches you, and it helps to look it in the eyes. I acknowledged it and then let it pass. I didn’t rehearse speeches I’d never give. I didn’t parse Tessa’s motives like a code I could crack. Some locks protect emptiness. Some puzzles are insults to your intelligence.

I wrote another line on my What I want page: Holidays without a ledger. I meant a table where I bring a pie because I made it, not because it runs cover for a late payment somewhere else. I meant gathering for the warmth of it, not the transaction. If that table never existed with those people, I could build one with others. Or I could eat a good dinner alone with a candle lit like a person who knows celebration can be singular.

On a Sunday I took out the box of ornaments, the ones I’d kept when I moved to the condo. My childhood had lives in those shapes: a little wooden soldier missing a foot; a ceramic star; a paper snowflake made by hands that haven’t been small in a long time. I packed a few to donate. I kept a few. I didn’t posture about meaning. I chose, and choosing felt like a skill I was finally allowed to be good at.

When the first cool front arrived, the sky over O Street went a brighter kind of blue. I put the herbs closer to the wall and imagined them feeling protected; I smiled at the ridiculousness of that and did it anyway. I wrote a letter I did not send. I loved you while I paid for you, it began, and then I crossed it out. I loved you beyond what I paid for you, and then I crossed that out, too, because that sentence still made money the measure. I wrote nothing else, folded the paper, and slid it into the binder on the top shelf between the statements. It wasn’t for them, it wasn’t even for me in some future reckoning. It was for the shape of the story—how it holds still when you put the right marker in the right place.

The anniversary of the prom text passed without fanfare. I noticed because the light looked like it did that morning—thin and decisive—and because my body let me know that it remembers landmarks. I marked it by making pancakes and leaving the dishes in the sink for a few hours, an indulgence I used to mistake for negligence. Nothing broke. Nothing burned. Time did its job without my supervision.

Ellen and I scheduled one last meeting, the kind you have when a project is over and not merely paused. She brought a checklist, because of course she did, and we walked through it: passwords, alerts, access settings, the language at the bank, the credit monitoring I’d installed even though it made me feel like I lived under a bell jar. We left nothing dangling, nothing to come back and haunt me in a low tide of attention.

“You’re set,” she said, closing the folder. “If anything changes, you’ll know.”

“I’ll know,” I repeated, and liked the competence of the sentence, the way it belonged to the future without asking the past for permission.

We hugged. It wasn’t the obligatory kind you do at office parties to prove you’re human. It was the brief, fierce kind shared by two people who chose a tool and used it well.

On a walk that evening, I passed the corner house where the flag caught and released the breeze with a sound like a polite applause. The street was full of small kindnesses. A neighbor had set out a box labeled FREE BOOKS and meant it. A kid had chalked a hopscotch grid and left it there for any stranger to borrow joy. A dog sighed from a porch. There was nothing to solve.

I pictured the younger version of myself who believed usefulness was the same as worth. I wanted to tell her that she was more than her wire transfers, more than her spreadsheet heroics, more than the way she could make a crisis feel like a plan. I wanted to tell her that being reliable is a virtue until it becomes an alibi. But she wouldn’t have heard me then. She hears me now. That’s enough.

At home, I made a small ceremony of closing the binder for good. I took it down, set it on the table, and opened to the cover sheet I’d added—Closed and Do Not Reopen. I slid the unsigned letter inside and added a final page titled Notes. I wrote three lines:

-

- Love is not a wire transfer.

-

- Boundaries are doorframes.

- I am allowed to be brief.

I put the binder back and stood in the doorway to the hall closet and felt the odd satisfaction of a shelf that holds.

I did not need a moral victory. I didn’t need apologies performed under bright lights or public acknowledgments of harm. I needed my life. I had it.

When fall settled, I bought a heavier blanket and a candle that smelled like sensible apples. I invited two colleagues over for dinner—not to prove I could host or to audition for a different family, just because roasted vegetables are better shared and friendship is a slow‑growing plant. We ate at my small table and laughed the way you do when no ledger is hiding under the placemats. We washed the dishes in the sink without choreography. They left, and the quiet that followed was warm.

Prom photos eventually swept through the same internet that carries every version of every life. I didn’t hunt them down. A picture found me anyway, through the algorithm that believes proximity should be destiny. Rhinestones, pale fabric shaped like a statement. The dress had the hollow glamour of an occasion that believes itself important because it is expensive. I looked for a second. I closed the app. I put my phone face down. I didn’t feel righteous. I felt done.

The last thing to cancel was a habit you can’t find in any settings menu: the reflex to turn myself into a plan the moment someone else goes hungry for convenience. You don’t revoke access to that with a bank letter. You starve it. You replace it. You make new pathways with repetition until your own life feels like the default rather than the thing you get to experience after everyone else is squared away.

So I wrote a new automation for myself that ran every morning, the kind without code: Choose what you want. It wasn’t a rebellion. It was maintenance.

I chose to run when the air was honest. I chose to sleep without watching my phone. I chose to buy the cereal I like. I chose to look at my budget and feel steadied instead of scolded. I chose to donate what I didn’t use. I chose to keep what I loved. I chose to keep going.

On a clear Sunday afternoon, I carried a small box to the thrift store again. Inside: champagne flutes I’d bought years ago for the kind of parties that end up being about performance and not presence. The bell over the door did its cheerful clatter. The clerk—different from last time, but the same species of kind—took the box and set it gently aside. “Big occasion?” she asked, because people ask; it’s how they open a room.

“Just a little spring cleaning,” I said, even though the calendar said fall. She nodded like seasons could be personal. Maybe they can.

On the way out, I saw the girl who had once tried on the dress. Not that girl; another one, with a different braid, a different face learning it could be beautiful. She laughed in a mirror. The moment tugged at me and then released me. Joy doesn’t need an audience to count.

I walked home the long way. The flag at the corner house moved in a wind that smelled like distant rain. My balcony herbs lifted their small green hands and did not dramatize thirst. The hinge did its steady duty without complaint. I unlocked my door and stood in the liminal space where outside gives way to home. I listened for any old alarms and heard only the hum of the fridge and the soft insistence of my own contentment.

I put the receipt in the Charitable folder because consistency is a gift I can give myself. I poured water into a glass and drank it standing at the sink because sometimes you don’t need ritual; you need hydration. I set my phone on the counter and the lock screen lit. The sentence glowed back at me from a small rectangle of glass like a lighthouse you can carry.

You made the right choice.

I tapped the screen once more, and the second sentence—my morning automation—scrolled into view like a final line on a page that had asked to be written for years and was finally getting the ending it deserved.

Choose what you want.

So I did. I chose a book and a blanket; I chose an early bedtime; I chose another ordinary day on the other side of extraordinary decisions. I chose to let the past do what the past is supposed to do: stay where I put it. I chose to keep going in a life measured not by emergency, but by the steady ledger of enough.

And when the lights went out, the condo breathed with me. No alarms. No invoices disguised as affection. Just the sound of a home that knew its owner. The sentence on my phone waited for morning. The world turned over into night cleanly.

I slept. The choice held.

You made the right choice.