Right After I Gave Birth My Husband Decided To Invite The Whole Family. Everyone Congratulated Us…

I didn’t know a life could pivot in the space between a blessing and a breath. I didn’t know a day could be both the happiest I had ever known and the most terrifying. On March 12, 2025, under fluorescent lights and the antiseptic hush of St. Augustine Medical Center, our daughter arrived. Seven pounds, three ounces. Ten fingers I counted twice, ten toes I counted three times, as if the universe might change its mind if I didn’t keep watch. We named her Emma. When her tiny fingers curled around my index finger—instinct, gravity, grace—the world pulled into focus so sharply it almost hurt.

“My girls,” Derrick whispered. He had been a restless satellite orbiting the bed, taking pictures that blurred because his hands wouldn’t stop trembling. He kissed my forehead and my damp hair, giddy and exhausted, and said the sentence that would set the rest of the day in motion: “We should celebrate with everyone. I want both our families here to meet her.”

“Tonight?” I asked. Fourteen hours of labor had left me hollowed and shining, like a bell just rung.

“Tonight,” he said, already composing the group text. “They won’t stay long. Just hello and congratulations and then we’ll sleep. It’ll mean a lot to them.”

The nurse adjusted Emma against my chest. Somewhere down the hall a monitor chimed, then quieted. It felt safe in that way hospitals sometimes do, like every emergency had a plan. My husband’s grin was contagious. I nodded. “Okay. Invite them.”

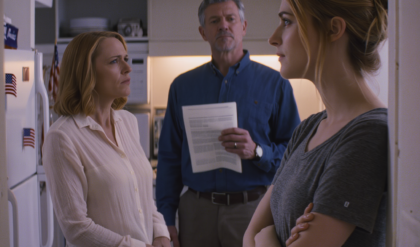

He tapped out the messages with the eagerness of a teenager who’d just passed his road test. His parents, Richard and Susan, replied within seconds: We’re on our way. His sister, Michelle: I’m bringing a diaper bag full of treasures. I love you already, Emma! I could see his family in my mind—warmth, noise, happy chaos.

My phone buzzed a few beats later. My mother: We’ll be there. Vanessa is with me. No message from my father. I told myself he was probably in clinic, or returning calls, or doing whatever it is he uses to defend the distance he’s perfected over decades. It did not matter, I told myself. Not today.

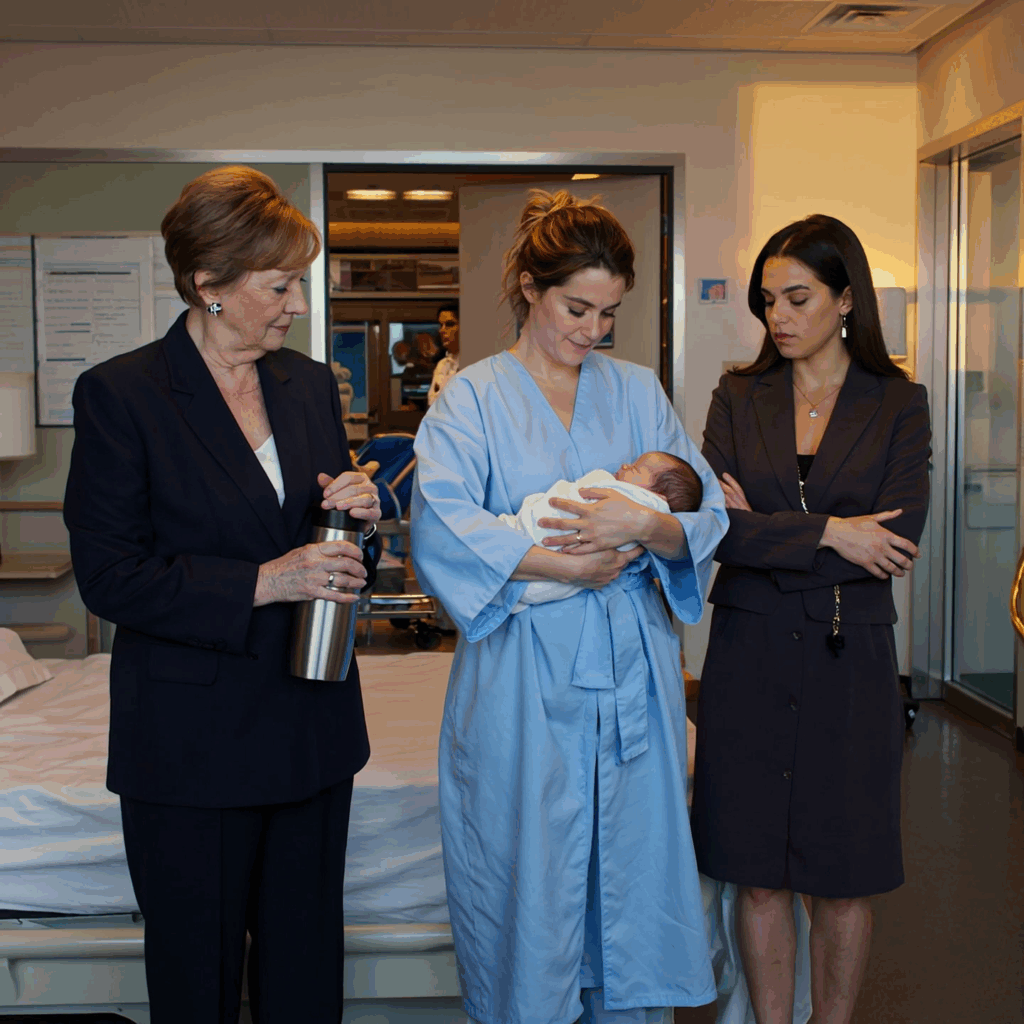

The room became a brief, perfect tableau when Derrick’s family arrived first. Richard was careful with his size and joy in equal measure, a big man who had learned to make himself smaller in hospital rooms. He carried an enormous teddy bear that would take up half the nursery and none of the crib; he put it on the couch and laughed at himself. Susan had crocheted a blanket in soft sea-glass colors, cotton that wouldn’t itch Emma’s new skin. Michelle breezed in with a diaper bag that looked like Mary Poppins had stocked it—wipes, pace-changing pacifiers, tiny socks with smiling clouds. They took turns washing their hands at the sink and hovering near the bed, their faces lit with the kind of wonder that doesn’t overstay.

“Hi, sweet girl,” Susan whispered to my daughter, and then to me, “You did beautifully, Rachel.”

I believed her for a second. The room hummed with congratulations and stories about Derrick’s own chaotic birth—how Richard had driven Susan to the hospital at 3 a.m. in a pickup with a cracked windshield because the sedan wouldn’t start, how a nurse with a voice like a foghorn had coached Susan through the last push. They stayed for an hour and a little more, offering love and trash bags to take the florist-levels of balloons later, offering help without hovering. Happiness has a sound; it’s softer than you think.

My mother and my sister, Vanessa, arrived twenty minutes after Derrick walked his family down to the parking garage. In that small gap, the room exhaled. It inhaled again when my mother pushed open the door, but the air felt different. Cooler, thinner, as if the HVAC had decided to misbehave.

“Congratulations,” Mom said, smiling in a way that pulled too hard at the edges. She held a small gift bag, pharmacy-sized. Vanessa hovered behind her near the door, arms crossed, a stance so familiar from childhood it may as well have been a uniform.

“Hi, Mom. Hi, Ness.” I used the nickname I had never retired, as if softening her name might soften her.

Mom set the bag on the tray table. Inside was a single onesie, unwashed and cheerful, the kind of thing you grab near a register when you remember you should bring something. I told myself not to compare, not to tally the gifts of one family against the offerings of the other. But when Vanessa stayed near the threshold and stared at Emma like my baby had personally wronged her, something old and wary rose in me.

“She’s… small,” Vanessa said, as if the word tasted bad.

“She’s perfect,” I said, and heard the steel in my voice.

They didn’t sit. They didn’t wash their hands. They didn’t ask to hold Emma or to touch her soft hat or to hear the story of her name. They made a triangle of silence with the far corner of the room, the door, and my bed. My mother’s smile flickered like a bad bulb.

“Where’s Derrick?” she asked.

“Walking his parents down. They forgot Richard’s phone.”

“Oh,” Mom said, as if that meant something else entirely. She unscrewed the top of the stainless-steel thermos she’d brought—the same kind she’d used at my soccer games when I was nine, the same click of threads. Steam rose. Chicken noodle soup. My childhood in a scent.

The door closed behind Derrick’s family, and something in the room closed too. It was a feeling you get sometimes in winter when a weather system changes all at once.

“You actually went through with it,” Vanessa said then, voice cool and precise, venom wrapped in grammar. She took two steps forward. “You knew I’ve been trying for three years. You knew about every appointment, every negative test. And you still did this.”

“Did what?” My brain, newly rearranged by labor and shock and joy, fumbled for what she meant.

“You flaunted your fertility,” Vanessa said. “Like always. You do something, and it makes me look like a failure.”

It was such a ridiculous sentence that, for a heartbeat, my mind reached for a laugh that did not come. I tightened my hold on Emma. “I didn’t do anything to you,” I said. “I had a baby. That’s not about you.”

“Everything is about you,” she said. “Pretty Rachel. Married first. Baby first. Look at you, center stage.”

My mother put a hand on Vanessa’s shoulder. It looked like comfort if you didn’t grow up seeing it as a warning. “Rachel, honey,” she said, drawing out the second word like it could be sweet if you stretched it thin enough. “You need to understand what your sister is going through. This is hard for her.”

“Mom, this is a hospital,” I said, keeping my voice low. “My newborn is asleep.”

Mom’s eyes flicked to Emma in a way that did not feel like love. “Vanessa is my firstborn,” she said, the truth too plain and too late. “She needs me more. She always has.”

Sometimes a lifetime collapses into a sentence. I should have felt a part of myself shovel dirt onto a coffin. I should have felt something break. Instead, there was a kind of calm that comes when your worst suspicion stops pretending to be anything else.

“My favorite daughter can’t have children,” Mom said, her voice brightening like a commercial. “I will never accept your baby as part of this family.”

Time, which had been moving properly a second ago, slowed. Mom’s arm lifted. The thermos tilted. I didn’t think; I moved. Instinct is faster than thought. I turned my body and curled around Emma the way you do in drills you hope you never need. The soup arced, a bright, terrible line. Heat hit my shoulder and then the tiny exposed bit of Emma’s cheek and forehead where the hat didn’t cover. Her scream split the world. It was a sound I had never heard, a sound that would plant itself in the soft places of my brain and wait for dark.

I hit the nurse call button so hard my thumb ached. “Help!” I yelled, and my voice came from far away. “Help. My baby.” Emma writhed against my chest. I pulled the blanket away and tried to cool the skin with the edge of fabric that hadn’t been hit, tried to do three things at once with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking.

Vanessa laughed. It was the sound of someone slipping on ice and being glad it wasn’t them. “Finally,” she said. “Finally something goes wrong for perfect Rachel.”

The door banged open like a sentence ending. Two nurses flooded the room, fast hands and clipped voices. One took Emma with practiced gentleness, already speaking the language of burns—cool water, assessment, pediatrician on call, ER consult just down the hall if needed. The other slid an arm under my elbow and helped me stand even as I protested that I had to go with my baby. “You’re coming too,” the nurse said. “You’re okay. We’ve got your daughter.”

Security arrived as if conjured. My mother set the thermos down on the floor, sideways, soup puddling toward the wheels of the IV pole. She looked at me like a stranger who had cost her something. Vanessa crossed her arms again, her mouth in a line of ugly satisfaction.

“Ma’am,” one of the guards said to my mother, “you need to come with us.” He used the voice that sounds like a suggestion and is only a suggestion in the way a fire alarm is.

They were almost at the door when Derrick burst in from the stairwell, his face gone the color of paper. “Rachel? What—” He saw the nurses, Emma’s pink face furious and wet, the guard’s hand gentle but firm at my mother’s elbow. Everything on his face shifted at once. Behind him, taking the kind of careful steps you take in a place with rules, came Richard.

Richard stopped. The recognition on his face was a physical thing, like wind hitting a open umbrella. “Diane,” he said, and my mother’s name sounded like he’d been carrying it around braced for it to break.

My mother stared at him. All the color left her skin. “Richard,” she said, small.

They stood there for one long breath with thirty-five years pressed between them, and then the present reasserted itself with a wail. My daughter’s. Mine, inside.

Richard found his voice first. “We’ll talk about the past some other time,” he said, voice low and controlled in the way you have to be when you’re not in your own house. “Right now, the police need to be called.” He looked to the head nurse and then at me. “Rachel, I’m so sorry.”

They took statements in a small room off the pediatric floor while the doctor—Dr. Martinez, calm and precise—cooled Emma’s skin and reassured us she was likely looking at first-degree burns, painful but superficial. “No blistering so far,” she said. “You moved fast.” She gave me a look that anchored me to my chair. “You protected her.”

Security escorted my mother and sister down to the first floor to wait for the police. Derrick sat in a chair with his hands in prayer against his mouth. Susan arrived with Michelle and didn’t ask questions; she put a hand on my shoulder and stood there like a pillar you could lean on without anyone calling it weakness. Richard spoke quietly in the hall with the officer who took the report, his posture a wall around our small room. We were not alone.

The officer asked me to tell what happened. I did. I said the words “threw hot soup at my newborn” and felt all the blood in my body choose a new direction. I said “my mother” and the officer’s eyes did a small, human thing he couldn’t hide before he caught himself and wrote it down.

When the statements were taken and the pictures of Emma’s skin documented for the file, the officer asked if I wanted to request a restraining order. The answer was already breathing inside me. “Yes,” I said. “Immediately.” He nodded and explained the process—temporary order first, then a hearing for a longer one, judges, paperwork, signatures, everything in American bureaucratic due process that exists because people do the kind of things that make you need it.

Emma’s cries gradually softened into hiccups. She slept against my chest while I gave my statement the second time for the hospital’s incident report, and a third time for the detective who’d come on duty. Exhaustion hit like a tide, then ebbed, then hit again. Somewhere around 9 p.m., after Emma’s vitals were checked one more time and a pediatric burn specialist peeked in to confirm what Dr. Martinez had already said, the police notified us that my mother had been arrested on suspicion of felony child abuse and assault.

“Rachel,” Richard said quietly after the officer left. “About earlier.” He didn’t say my mother’s name again. He didn’t need to. “We were engaged. A lifetime ago. She left three days before the wedding. Emptied the small savings we had, and disappeared. It took years to understand that the leaving was a gift. But it didn’t feel like that then.” He swallowed. “I never knew she married your father. I never knew she had you.”

There was no mention of affairs or what-ifs or romantic tragedies. There was only a young man who had been left and a man who had built a better life, who had shown up for his children and loved his wife and carried the scar like the rest of us do—quietly, in private. I looked at Susan and saw in her face not jealousy, not triumph, but something like fierce relief that the present was real and the past was over.

“Whatever history there was,” Susan said gently, “it doesn’t excuse what she did today.”

No one disagreed.

We took Emma home forty-eight hours later with a list of instructions and tiny packets of ointment, an appointment with the pediatrician for the following week, and numbers to call if anything changed. The pinkness on her cheek was already lightening. Dr. Martinez had been right about first-degree. We’d dodged worse by inches and by instinct and by the speed of nurses who run toward noise.

Our front door looked different to me. Home should look like a landing. It looked like a checkpoint. I set the car seat down in the living room and put my hand on the handle the way some people lay a palm on a church pew.

In the beginning, the hours were measured in ounces and burps and sleep cycles that made no sense to anyone not actively negotiating with a newborn. Susan came during the day when Derrick had to go back to the office, the way some mothers-in-law arrive and make things easier without making you feel replaced. She watched Emma sleep while I took showers I didn’t rush, folded onesies into piles that looked like a doll house had spilled into my life. She told me stories about Derrick and Michelle as babies that were both specific and encouraging—how Derrick hated his car seat until he didn’t, how Michelle learned to roll over in a living room that for a week became a soft obstacle course.

Richard stopped by after work with dinner in paper bags and a look that said he knew what it was to be tired and not want to think about imaginary spinach. He held Emma with a carefulness that made me tear up. He never mentioned my mother unless I did, and even then he kept the conversation anchored to the present like a good captain.

I applied for the restraining order the morning after we got home. The form asked me to describe what happened. I did, again. The clerk looked at me with kindness shaped by repetition. “We see a lot,” she said softly. “I’m sorry you needed to meet me today.” The temporary order was granted by noon. Papers were served that evening at the county jail.

My phone became its own kind of courtroom. News traveled fast inside families and faster outside them. People texted who never text. Congratulations collided with gossip. A cousin I hadn’t seen since a wedding three years ago wrote to say she’d heard something “crazy” and wanted to know if I was okay. A high school acquaintance sent a link to a local news segment that had already gotten the facts wrong in the ways that make of a life something consumable. Don’t read the comments, Derrick said. I read the comments.

Some strangers believed the worst version of me they could build from hearsay. She must have done something to provoke it. She shouldn’t have invited her family if her sister is struggling with infertility. She should forgive—family is family. Other strangers were kinder. None of them knew us. None of them were there.

“Turn it off,” Susan said one afternoon when she caught me scrolling, thumb angry. “Turn it off and look at your daughter breathing.”

So I did. Until the next time I didn’t.

I found a therapist two weeks in, after the pediatrician—Dr. Martinez’s colleague in practice—checked Emma’s skin and said the words “healing beautifully,” and then looked at me and asked, gently, how I was sleeping. “On and off,” I said. “Mostly off.” She gave me a list of names. Dr. Chen had an opening on Tuesday at 2 p.m. I took it the way you take a life preserver.

“You don’t need permission to protect your child,” Dr. Chen said in our second session after I confessed the tiny, ugly fear that maybe I had overreacted by pressing charges against my mother. “You don’t need a jury of internet strangers to vote you innocent.” She said it like she’d cleaned the sentence with a cloth. “What happened was wrong. You are allowed to feel what you feel.”

I kept expecting the feeling to be fury. Sometimes it was. More often it was something like grief’s cousin—the version that sits quietly at the kitchen table and watches you wash bottles and doesn’t speak.

The police called twice in that first month to clarify details, to ask if the temporary restraining order had been violated (it hadn’t), to confirm the date of the hearing for a long-term order. The assistant district attorney called to say the case would proceed. “We have video from the hallway camera,” she said. “We have witness statements. We have the doctor’s report. I’m sorry you’re in this position, Ms. Whitman.”

Whitman is my maiden name. I felt the old pride in it, a surprised reflex.

My father emailed me for the first time in years. The subject line said: I’m sorry. The body said: I didn’t see it. The second email said: That’s not true. I saw it. I told myself it was discipline, or temperament, or something else that didn’t require me to get between you and your mother. The third email said: I will sell the house. I will do what your lawyer asks in the civil suit. I want to fix what I can fix. He did not ask to see Emma. He did not ask for forgiveness. He asked for a chance to not make it worse.

“Do you want to respond?” Derrick asked, reading over my shoulder the way you do when a person you love is standing next to a match they could strike.

“I don’t know,” I said, which was the truest thing I had said all day. “I want to want to.”

“Then take your time.”

The preliminary hearing happened on April 5. I wore flats because I didn’t trust my knees. The ADA walked me through what to expect. The defense attorney floated “temporary emotional disturbance” in the way you float a trial balloon to see who salutes. The judge didn’t salute. He set a trial date for early November and encouraged both sides to move discovery along like adults.

Mom’s first letter arrived in May. It was full of the kind of sentences that put responsibility on weather and hormones and a generalized you that could be anybody. I’m not myself. I was overwhelmed. I didn’t intend. The you is underlined. The word sorry appears once like a misprint. I put it in a drawer without replying. When I told Dr. Chen, she nodded. “You don’t owe her a letter,” she said. “You don’t owe anyone an explanation for protecting your child.”

Dad’s emails changed shape over the summer. The first ones had defense braided into regret—therapy words used like decorative pillows, correct but untouched. The later ones started leaving space between the lines where honest breath could fit. He wrote that his therapist had asked him, What would you do if you saw a stranger treat a child the way your wife treated your daughter? He wrote: I would intervene. I would call 911. I would do anything. I didn’t, because it was us. The us was underlined. He wrote: I am learning the difference between conflict avoidance and moral courage.

I answered once, in July. I said: Emma is six pounds heavier and watches ceiling fans like they are opera. I said: We are okay. I did not say forgiveness. I did not say visit. He wrote back: Thank you for telling me about her.

Richard started stopping by after work once a week with takeout from whatever place looked like it had good reviews without being too proud to use paper napkins. He told me stories about raising Derrick that made me feel both less alone and more equipped—like the time Derrick wouldn’t get in the bathtub for three nights straight and then, suddenly, couldn’t be coaxed out of it without bribes. He didn’t talk about my mother unless I did, and then only to offer context that didn’t excuse. “I was twenty-two,” he said one evening while Emma fell asleep on his chest. “I thought love meant ignoring bad weather. Your mother taught me that love sometimes means reading the forecast and getting in the car.” He smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes. “And then I met Susan, who is the whole map.”

I looked at him and saw not the man who’d been left at an altar that never got used, but the man who’d shown up for decades—carpools and colds and college tours, jokes told around big tables. The best revenge on a past that tried to write you is to write yourself better.

The trial began on November 10. The courtroom was colder than it needed to be, which I decided was a kindness. The ADA presented the footage. The nurses testified. Dr. Martinez explained first-degree burns in words the jury could understand without googling. I took the stand and said, “My mother threw hot soup at my newborn,” and didn’t cry. Derrick testified to what he saw when he walked in, to what he saw in me after. Richard answered questions about being present and about recognizing my mother, and the judge kept the past where it belonged—background, not justification.

The defense tried to make Vanessa’s pain into a mitigating factor. The ADA did not allow the courtroom to turn into a talk show about competing sufferings. The law is not good at feelings; sometimes that is a strength. After four hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict: guilty on felony child abuse and assault. The judge sentenced my mother to six years in state prison with eligibility for parole after four for good behavior.

I did not feel triumph. What I felt was a series of doors closing in a house I thought I knew. Some of those doors revealed new rooms behind them—rooms where safety lived, rooms where the word boundary was not an insult.

The civil case took its own slower course in a different building two blocks away. Dad agreed to settle. He sold the house I grew up in—a split-level with too much carpet and a backyard that had hosted a hundred summer dinners—and gave me half the proceeds. He filed for divorce. My lawyer called it damages. Dr. Chen called it restitution. I didn’t call it anything. I opened a college fund for Emma and paid the therapy bills and put the rest where I couldn’t see it day to day.

Dad asked, humbly, for supervised visits with Emma. “She deserves a grandfather,” he wrote. “If I am not that man yet, I want to become him.” I said yes with conditions a contracts professor would admire. The first visit was at a park on a Sunday in January, thin winter sun and kids in puffy jackets that made them look like stars. Derrick came with me. Richard insisted on coming too, not as a guard but as a guarantee. Dad held Emma like she was both fragile and resilient, which is a good way to hold a baby and most truths. He did not mention my mother. He did not ask for more than I’d offered. When the thirty minutes were up, he handed her back without leaning on sentiment as an argument. “Same time next week?” he asked. “We’ll see,” I said. We saw.

Vanessa texted twice in the spring from numbers I didn’t recognize to say that “family forgives,” which is a sentence often deployed by people who have never apologized. Then she sent an email from her own account that said I hope you’re happy. I blocked her in the places where blocking is possible and told Dr. Chen about the places where blocking is a practice you choose again and again.

Mom’s letters kept coming. A few sounded like the person who raised me—sharp, manipulative, bending the light. A few sounded like a person who’d been forced to sit with herself for longer than she wanted. In July, she wrote a short letter without underlines or excuses: I am sorry. I am in therapy. I am learning how favoritism felt like oxygen to me and poison to you. I did not expect the apology to move me. It did not. It did, however, shift a weight from my shoulders I hadn’t realized I was still carrying. I wrote back once to say Emma is healthy, we are well, I hope you find the help you need. I did not promise a visit. I did not offer forgiveness like a coupon code.

The restraining order hearing for a three-year extension took place in November the following year. Mom appeared via a video screen from the facility upstate, her attorney beside her. She looked older in the way people do when life gets measured aloud. My lawyer presented excerpts from letters that curved back toward manipulation, from messages Vanessa had posted publicly that turned my daughter into a moral proving ground. The judge granted the extension with a voice that did not invite argument. The order was clear: no contact, no proximity within five hundred feet of me, Derrick, Emma, or our home, no third-party messages, immediate arrest upon violation. On the screen, my mother’s face tightened for a second, the mask slipping enough to remind me that sometimes therapy teaches people better costumes.

We walked out into cold air that made everything smell clean. Derrick took me to lunch at a diner with coffee that tasted like memory and a BLT that tasted like reward. We talked about Emma’s birthday party and about the way time moves differently when you measure it in firsts.

Some evenings the house glowed in the ordinary way that made my chest ache. We grilled burgers on the back patio in July and watched fireflies stitch the yard. Emma started kindergarten in August with a backpack too big for her shoulders and a grin that showed the gap where her front tooth had been. She called Richard “Granddad” and Susan “Nana,” names that fit them like clothes they had owned forever. She called my father “Papa” after six months of supervised visits, a name he had not asked for and did not hide his tears about when she said it the first time over a plate of pancakes. He showed up every time he said he would. He kept going to therapy. He brought library books and small wooden puzzles and asked me what boundaries I needed that week. He did not try to skip steps.

I thought healing would feel like a fireworks finale. It felt more like maintenance—quiet and repetitive. We chose no contact where that was salt, and cautious contact where it was salve. We built routines that did not apologize for protecting what we had built. We learned the difference between bitterness and boundaries, which is often the difference between being stuck in a story and having one.

On a Sunday in late September, Richard brought over a box of old photographs and we sat at the dining table while Emma turned them into a game. “Who is that?” she asked, pointing to a picture of Derrick as a chubby toddler covered in chocolate frosting. “Your dad,” I said. “He’d just discovered cake.”

Richard handed me a picture I hadn’t seen before: a college campus in black-and-white, a young man whose face I recognized and a young woman I would have recognized anywhere if I had been ten feet away with my eyes closed. They were smiling like they had just invented the idea. “You can keep that, if you want,” he said, and there was no agenda in it. I looked at the picture and did not feel the old swoop in my stomach that used to accompany the idea of my mother’s other lives. I felt what you feel when you file a paper in a cabinet. Useful. Over.

Michelle became my friend in a way that wasn’t inevitable and therefore felt like a gift. She dropped off coffee and pastries in the early weeks when the days felt like paste. She texted me memes in the middle months when I needed to be reminded that laughter didn’t require permission. She invited me over for lunch one day in May and we sat on her small balcony with iced tea and talked about everything and nothing. “Families are complicated like weather,” she said, staring at the skyline. “But you can keep a raincoat by the door.”

The settlement from the civil suit sat in an account with Emma’s name on it. We used some for therapy and some for the kind of surprises life throws at you when your car tire finds a nail and you can’t find the time to find a tow. The rest waited quietly for a future that would be hers to decide. When I thought about the money, I let myself think of it as something my father had finally given me more than something my mother had cost me.

There were still nights. The ones where the sound of a pot lid hitting the counter made a noise that made me breathe too fast. The ones where a headline shared by a friend who meant well put the room full of strangers’ opinions back into my palm, heavy. Dr. Chen called those nights data points, not definitions. “You’re not back in the hospital,” she said when the old panic flared. “You’re in your kitchen. Your daughter is asleep down the hall. Your husband is at the sink. You are safe.”

The day Emma turned five, we measured her height on the kitchen door frame with a pencil. She stood tall and proud, chin up, the way kids do when you make measurement feel like victory. “Again,” she said after the mark was made. “I want to be taller.”

“You will be,” I said. “You’re growing right now.”

Derrick laughed and picked her up until she squealed. I looked at them and thought how, on the day she was born, I had believed we were safe because we were in a building with policies and a floor plan. And we were. But safety, I learned, is also a practice. It is a collection of decisions: The number you call when you need help. The paper you file even when your hand shakes. The people you let in and the ones you keep out. The stories you tell yourself about what you deserve.

If you asked me now what my revenge was, I would point to the ordinary things. The dandelions Emma brought me from the backyard, fists full of gold we put in a glass of water and treated like roses. The way Derrick reached for my hand at stoplights. Susan’s habit of folding laundry like it was origami and leaving it on our couch with a note that said, Proud of you. Richard’s knock at the door at 6 p.m. on Thursdays, right on time, holding chicken alfredo that tasted like somebody had said yes to butter without apology. My father’s careful texts: Can I take Emma to the park at 10 a.m. on Saturday? I will have her back by noon. The way he always arrived at 9:58.

I did not build a life in defiance of my mother. I built it independent of her. The difference is not small.

People sometimes assume that because the worst moment of my life occurred in a hospital room, I hate hospitals. The opposite is true. I like their competence. I like the way the halls smell like something is being handled. I like that there is a button you can press and the pressing makes something happen. When I walked back into St. Augustine Medical Center for a routine checkup a year after Emma was born, the nurse at the desk smiled in the way that says I recognize your face but I will not say from where. That privacy felt like a mercy I hadn’t known I needed.

On the way home, I drove past the park where Dad had first held Emma. He was there on a bench with her on his lap, now almost two, pointing at a squirrel like she’d discovered a new species. He waved, tentative, and I parked and joined them. He handed me a small envelope. Inside was a card with three sentences that were a better apology than his first ten emails combined. I don’t deserve this chance, it said. Thank you for letting me try. I will never turn away again. I believed him for the length of a breath and then decided to let his actions keep proving it.

At night, when the house is quiet and the yard hums with whatever hums in yards, I sit on the back steps with Derrick and we talk about nothing in particular. Weather. Work. Whether we might try for another baby in a year or two when the time feels good and the memory of the worst day of our lives has been diluted by a thousand better days. We say their names out loud sometimes—Susan, Richard, Dr. Chen, Dr. Martinez, Dad—like a roll call of people who showed up. We do not say my mother’s name. It exists without being invited.

“Are you okay?” Derrick asks sometimes, not because he doubts but because he wants to be the person who confirms.

“Yeah,” I say now. It is not a performance. It is not a lie. It is the most accurate word for a life that is both fragile and durable and full.

Emma runs through the yard chasing fireflies with a jar that has more holes than fireflies because we decided that catching light should always come with a plan to let it go. She brings the jar to us and says, “Look, Mommy,” and I look the way you look when someone offers you a miracle caught gently on purpose. Derrick wraps an arm around my shoulders. The sun slides down behind the fence.

The night my husband invited both our families to the hospital, everyone congratulated us. Some meant it. Some didn’t. The congratulations were not the point. The point was what we built after, with clear eyes and steady hands, with police reports and court dates and therapy appointments, with baby giggles and first steps and the slightly crumpled flower stems of a child who thinks weeds are treasure.

The scars—physical and otherwise—are part of the story now, not the whole book. The outcome didn’t change: my daughter is safe; my marriage is strong; our family is the one we choose every day. The timeline didn’t change: the soup, the scream, the nurse, the report, the order, the court, the sentence, the letters, the boundary, the backyard. What changed was the idea that blood defines everything. It doesn’t. Love does. Boundaries do. Showing up does. And in the quiet after the day is done, when Emma falls asleep with her hand on my shoulder and Derrick closes the back door against the night, I feel something I could not have imagined in that hospital room: peace that doesn’t need permission.