We needed it more than you.

Kyle said it without blinking, like the sentence didn’t have sharp edges, like it wasn’t about every overnight shift, every clearance rack I’d learned to turn into a runway, every tiny miracle that added up to a small business that finally had a second front door picked out. He stood across the kitchen like a man auditioning for a role he’d already given himself—arms folded, chin tilted, a smirk that thought it could pass for confidence. He had no idea what he’d just woken in me.

I looked him in the eye the way you look at a siren that’s getting closer: steady, unblinking, measuring. “Then you won’t mind what’s coming next.”

Two hours later, the door shook on its hinges, the word POLICE cut the room in half, and the man who had snorted at my empty accounts forgot how to smirk.

My name is Rebecca Mitchell. I’m thirty‑four. I own a small boutique called Mitchell Designs. Every dollar in my world has fingerprints: my parents’, mine, my tailor’s, the seamstress who switches out a bobbin like she’s been doing it for forty years, my vendor who drove a box truck through freezing rain to get me eight bolts of deadstock wool when a shipment got stuck in Ohio. Money in my life isn’t theoretical; it’s the snap of a price tag, the scrape of a zipper, the soft thunk of a receipt drawer, the whoosh of the steamer when we open at ten.

That one hundred twenty thousand dollars wasn’t a number on a screen. It was the second lease I’d fought to negotiate downtown after three visits, it was the first month’s payroll for two new hires whose résumés still sit pinned to a cork board in my office, it was the expansion order to a woman‑owned dye house in Vermont that had already mixed Mitchell Blue, the shade I’d named after the chalky Portland sky that hangs over the Willamette before rain.

And my brother‑in‑law took it.

I didn’t start my life with enemies. I started with a bell above a door. I grew up in Portland, back of a hardware store that smelled like lumber, soap, and the mineral‑metal tang of nails. My parents ran Mitchell Supply like a promise: open by eight, lights off at six, Sundays after church if Mr. DeMarco’s water heater ever failed again. I learned inventory before I learned algebra. I could tell you the difference between 10d and 16d nails before I could tell you the difference between iambic pentameter and free verse. If a customer came in with a question, my dad would point to the shelves first and to a manual never. We carried the odd sizes because somebody always needed them.

Allison hated that store. My little sister chased different aisles—ones with mirrors and people. She had a laugh that collected friends, a calendar full of things that involved sequins or speakers. She wasn’t bad; she was just built for a world that clapped. I was built for a world that balanced.

Every summer I saved what I earned. I worked the register, swept sawdust that drifted like winter, learned to count back change in my head, and took home dollars that still smelled faintly of a coffee can. After college I stayed in retail, the corporate kind, and there’s a particular burn in your calves when you’re standing on polished concrete for twelve hours under air that’s been cooled to exactly the temperature a spreadsheet chose. I learned margins and markdown cadence and how to watch a shopper’s hand hover over a hanger and know exactly when to say, “We do have that in your size.”

I quit with five thousand dollars in savings and a stubbornness that could hold up a roof. Mitchell Designs opened in a space that used to be a bakery; the floors still remembered sugar. I bought secondhand mannequins, painted them, made them mine. I used a folding table as an office. For two years there was no such thing as a day off. Eighteen hours. Ramen for dinner. Shoes that wore out like erasers. I learned to stitch a hem because hiring a tailor wasn’t in the numbers yet. I learned to window‑dress because walking past should feel like being invited.

Then life found a way to teach me what a floor feels like when it opens.

A drunk driver ran a red light and my parents didn’t come home. Grief is an exact science when it wants to be. It counts hours, then minutes, then all the ways you can hear a phone ring in your head when you’re trying to sleep. The funeral smelled like lilies and lemon oil. The store keys were still on the hook by the back door, the rubber fobs with the raised numbers scratched from years of pocket change. The lawyer used words like estate and probate and I nodded because I couldn’t say anything else.

When the accounts settled, Allison and I each received seventy‑five thousand dollars. She stared at the figure like it could fix something. I stared at it like a blueprint. I put mine into the business. Lease renewed. Lighting upgraded. A POS system that didn’t crash in the middle of the lunch rush. A bulk order at a discount that felt like a secret handshake with the future. The store survived because those dollars were oxygen.

Allison drifted. She tried college again and then didn’t. She tried a job and then didn’t. Then she met Kyle at a casino and decided that what had been drifting was actually a tide pulling her toward a man who could fill every blank space with his certainty. They were married six months later.

From day one, Kyle had a voice like a sales pitch that never ended. He wore his hair slicked back and his watch like he wanted to be seen from space. At their wedding he took one long look at me like I was a balance sheet that had gotten uppity and said, “Your sister’s shop is cute. But real money’s in investments.” It was a sneer welded into a compliment, the kind of sentence that looks you in the face and tells you it’s doing you a favor by insulting you.

He dominated air. He had a way of speaking that treated conversation like a racetrack—laps around everyone else until you forgot where you started. Allison changed. There’s a way a woman’s shoulders round when she’s calculating the weather across a man’s face. She laughed less. She’d say Becca like it was a hand she wanted to hold and then glance sideways to check his reaction first. Phone calls became texts, and then texts became the occasional emoji disguised as connection. I have seen people slowly fold into their lives. My sister folded.

The lakehouse had been ours for as long as I had memories that smelled like cedar. It sits with its back to a stand of pines and its face to a slate‑colored sheet of water that keeps secrets for you if you ask nicely. Summers, our mother would make cold sandwiches and our father would insist that if you didn’t swim before lunch, you hadn’t really been to the lake. When I was nine, I found a jar of screws in the shed and sorted them by size for a whole afternoon. When Allison was nine, she found a skipping stone that crossed the cove like a miracle and named it Passport.

I arrived on a Friday afternoon with my trunk holding two overnight bags, a garment rack, and the kind of nervous‑excited energy you get when the math has finally aligned on paper and your life is about to step into the space you’ve drawn for it. The second location lease was in my bag, the vendor loan had cleared, and $120,000 sat in my accounts like a chorus line waiting for the curtain. I could see the new store in my mind: front door painted a blue that said come in, dressing rooms with doors that shut properly and mirrors that told the truth, a counter made from reclaimed fir because I will always love wood that’s been useful twice.

Cousin Emma met me at the dock. She is the family’s emergency contact for kindness; she can make bad news sit down and behave. She hugged me, then leaned in. “Allison and Kyle got here earlier. Just…be ready.”

Through the screen door I heard Kyle before I saw him. A voice too loud for the room, as if volume were a synonym for substance. Something about a real estate flip that would double anyone’s money if they were smart enough to get in now. Allison met me with a quick hug, said Becca like we used to say it at the bus stop, but her eyes kept skittering to Kyle as if they were on a leash. He raised a glass of whiskey and took me in with a smirk that called itself hospitality.

“The entrepreneur arrives,” he said. “Still selling enough dresses to keep the lights on?”

“We’re expanding,” I said, the we of it deliberate, the business bigger than me because that was always the point. “Just signed a lease downtown.”

“In this economy?” he scoffed, and I could have recited the paragraph he would say next. People like Kyle carry speeches like pocketknives. He liked terms like inflationary headwinds and liquidity and he would use them to cut your confidence into confetti if you let him.

Dinner was salmon and salad, the family talking in eddies around the big table, the lake pushing a hush against the windows. I helped Aunt Patricia prep—her hands competent even when they shook—and let the rhythm of chopping and rinsing calm my breathing. Later, when the house got quiet the way lakehouses do, I headed to the small bedroom I always take, the one with the quilt our grandmother pieced from fabric that remembers blouses and aprons. I set my laptop on the dresser, plugged in the cord, and went back to wash the last few dishes.

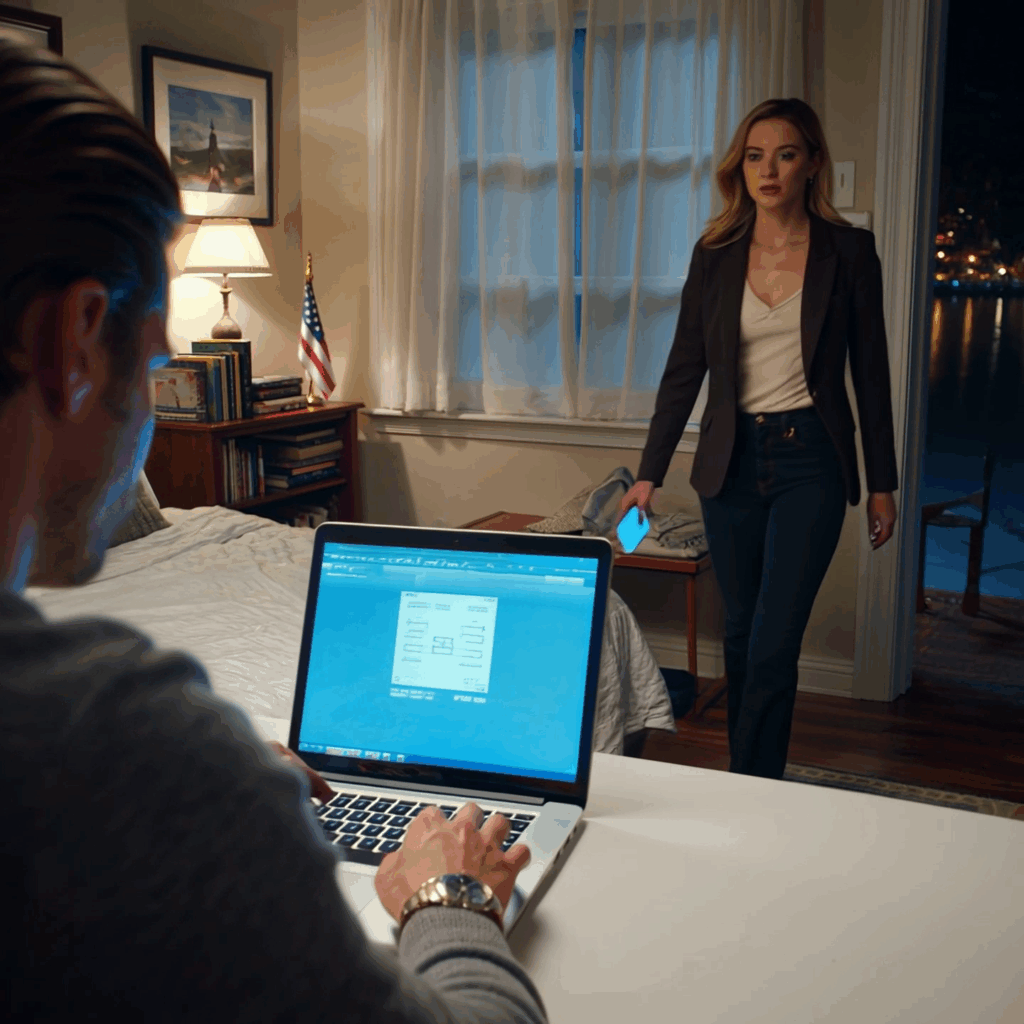

When I returned, my laptop wasn’t where I’d left it. Not exactly. The cord was in the other port. The screen was angled two degrees lower than my hands ever leave it. The microfiber cloth I keep under it had been moved a finger’s width. You learn to see small things when you run a small business, because small things become big things when they’re ignored.

I didn’t fling the door open and start accusing anyone. I opened the laptop, scanned the browser history—clean. I checked the logins—nothing obvious. Then my phone buzzed. New login attempt detected. Failed from an unrecognized device. The time stamp sat heavy. Somewhere between chopped parsley and the clatter of plates into the drying rack, someone had tried to move through my life like it belonged to them.

I changed every password. I enabled two‑factor authentication on anything that didn’t already demand it. I locked the laptop in my suitcase and slid the suitcase under the bed and stacked two hardcover books on the exit side of the frame because a sound is sometimes all you can afford for a warning. I lay down and stared at the ceiling until the knots in the pine looked like a map that wouldn’t tell me where I was.

Morning found me with a headache that drew fine lines behind my eyes. The kitchen smelled like coffee and lake air. I had just poured a cup when my phone rang. Claire. She’d been my manager, my mirror, my sanity when my own would do the thing where it walked into the stockroom and forgot why.

“Rebecca?” Her voice had a tremor I’ve only heard twice—once when the steamer exploded a gasket, once when her daughter broke her arm. “The vendor payment bounced. It says insufficient funds.”

I set the mug down and reached for my banking app with hands that suddenly didn’t feel like mine. The screen lit, the face scan clicked me in, and the numbers changed my breathing. Checking: $0. Savings: $0. Business: $0.

There is a particular silence that happens inside a body. It is not shock. It is the moment after shock when the world is still and you are the only thing moving and you’re moving with purpose.

It wasn’t a glitch. It wasn’t a hacker in a basement somewhere. It was someone who had sat under this roof last night and decided that what they wanted was more important than who would suffer. Overnight transfers—plural—to an account I didn’t recognize. I called the bank. When the rep answered, I put them on speaker, because if you’re going to set a fire, you might as well make sure everyone sees the smoke.

By the time I walked into the kitchen, conversations had slowed to a ripple. “My money’s gone,” I said, and the words felt like a foreign language inside my mouth. “All of it.”

Uncle Robert stood so fast his chair hiccuped against the tile. “What do you mean, gone?”

I held up my phone. The screen glowed with the kind of clarity that makes you want to throw it. “Over a hundred twenty thousand drained overnight. Transfers to an account I don’t recognize.”

Aunt Patricia made the small sound people make when they don’t have big words. Emma came to my side with the steadiness she has always kept in her pocket. Allison stared into her coffee like maybe the steam could fog out consequences. And Kyle folded his arms tighter, like he could press himself into a shape the truth wouldn’t notice.

“Have you called the bank?” Emma asked softly.

“I did,” I said, tipping the speaker icon up so everyone could hear what calm sounds like when it’s a stranger explaining your disaster. The rep’s voice came through, professional and antiseptic. Yes, Ms. Mitchell. Several transfers occurred starting at 11:42 p.m., ending at 4:15 a.m., from a recognized device in location. Your password and security questions were entered correctly.

The last sentence hit like a fist with a name on it. Correctly. Security questions answered. Not guessed. Not brute‑forced. Answered. There are maybe three people who know my mother’s first car. There are maybe two who know the song my father sang when he closed the store. There is one who might have sat close enough to my laptop to watch my hands.

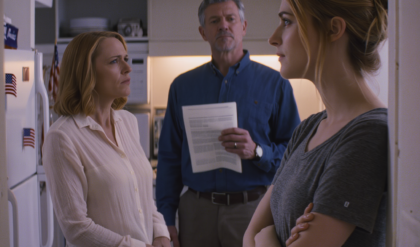

My eyes found Kyle. “You were near my laptop yesterday,” I said. “Were you in my room?”

Allison flinched like I’d thrown something. “Are you accusing my husband?”

Kyle smiled slowly, the way a cat smiles when it knows you can’t prove teeth. “Your sister’s paranoid. Maybe your partner mishandled the funds.”

“Then show us your bank statements,” I said. “If you’re so financially secure.”

His smirk twitched. It was small, the kind of movement a man doesn’t know his face has learned to make when it’s lying. “I don’t have to prove anything to you.”

“Oh, really?” I stepped closer. “Because if you didn’t do it, you’d be screaming louder than anyone in this room.”

Allison’s hands shook. She didn’t look at me. Kyle’s hand tightened around her waist, not in comfort, in control. And then he said it, cold and smug enough to frost the inside of a throat: “We needed it more than you.”

Rooms have temperatures. The kitchen dropped ten degrees. Aunt Patricia began to cry silently, the way people do when they are out of practice. Uncle Robert’s voice raised, a chord that sounded like the rope you throw to someone who’s gone overboard. Emma’s fingers pressed into my shoulder so I would remember where I was. I was already reaching for my bag.

“Then you won’t mind what’s coming next,” I said. My voice was not loud. It was steel.

Kyle lunged. “You’re not calling the police,” he barked, his hand reaching for my wrist like he owned it.

Uncle Robert stepped between us so cleanly you’d think he practiced for this moment every Sunday after church. “Back off, Kyle.”

Emma pulled me behind her, not because I needed protection, but because she knows that sometimes moving the target ruins the shot. Allison made a sound that wasn’t fear exactly; it was the sound of recognizing a cage when the door swings shut.

“Allison,” I said, softer now because sometimes the only way to be heard is to lower your voice and make listening a relief. “What’s really going on?”

She opened her mouth, but Kyle cut in, the words clipped and cruel. “We’re done here. Get your bags.” He tightened on the word we like he could make it a law. “We’re leaving.”

“You’re not going anywhere until I get every cent back,” I said. “Or I swear I’ll have you arrested before you hit the driveway.”

Kyle laughed. “Good luck. That money’s gone. Moved. Buried. You’ll never find it.”

Sometimes god, fate, or the universe develops a sense of timing so perfect it feels scripted. The front door crashed open and the word Police had a thread of authority in it that sewed everyone to the floor. Two uniformed officers entered, followed by a woman in plain clothes who showed her badge like it was a key she had been handed to fit this exact lock.

“Rebecca Mitchell?” she asked, looking straight at me.

“Yes,” I said, my heartbeat finally discovering a pace that made sense.

“I’m Detective Harmon with Portland PD. We received a fraud alert linked to your accounts.”

Kyle went pale the way milk goes pale in coffee—sudden, complete. “This is a misunderstanding,” he began, already walking toward her like momentum could make her agree.

“We have evidence from your bank’s cyber security team,” she said, her tone level, the kind that puts out fires and starts them when necessary. “Account transfers. Device IDs. And your face, Mr. Henderson.”

His mouth opened, and for the first time since I’d known him, nothing came out.

I reached for my phone, the same phone he’d tried to pull away from me, and tapped to open an app that saved me from the version of myself that still believed people will do the right thing because you have. “I installed security software last year after a hacking attempt,” I said, handing her the screen. “It takes photos during login attempts, tracks keystrokes, records access history. Here are the timestamps. Here are the IP matches. Here’s him at my laptop.”

Kyle’s mask slipped and the man underneath looked smaller. “You set me up.”

“No,” I said. “I protected myself. There’s a difference.”

The officers cuffed him. The click sounded like a lid going on something that had been spilling for years. He twisted to throw words at Allison because he needed someone else to be the floor. “You think you’re safe? You’re nothing without me.”

She stepped forward, her chin shaking but held high anyway. “I was nothing to you. Without you, I can finally be myself again.”

Detective Harmon scanned my phone, then looked up. “With this much evidence, you’ll likely recover most of the stolen funds,” she said, and her calm sounded like a bridge. “And more importantly, he won’t hurt anyone else.”

I have never realized how heavy my lungs are until the moment I let the breath out. It wasn’t over. It was just the part of the story where the ground stops shifting long enough for you to see how much you’ve stayed upright.

One month later, the second boutique opened in soft morning light. The front door had the blue I’d chosen. The racks held clothes that smelled like cotton and the future. Claire cried in the stockroom when the first customer asked for the dress in the window in a size medium and then another one to try because she couldn’t decide which made her feel more like herself. Mitchell Designs survived. Not because I got lucky. Because I was ready. Because I trusted the math in my gut. Because I refused to let betrayal be the thing the future remembered.

The bank recovered ninety‑seven percent of the funds within weeks; the rest was covered by fraud protection. Money isn’t the biggest victory in a life. It’s the thing that allows the actual victories to happen without bleeding.

The victory was Allison. She moved in with me. She filed for divorce. She reenrolled in school. The shadows under her eyes faded and the parts of her that had been quiet stood up and cleared their throats. She laughed again. She baked again. She talked to me while we chopped vegetables the way our mother taught us—keep your fingers tucked, make every cut the same so the onions cook like a chorus instead of a solo. She said, “You were brave for protecting what you built, Becca. I want to be brave enough to rebuild myself.”

She is.

Kyle pleaded guilty—to fraud, to coercion, to identity theft. He will be in prison for a long time. But his power ended the day Allison said aloud what she’d been whispering to herself for years: I’m done being afraid.

Last weekend we went back to the lakehouse. Not for a reunion. For a restart. We painted the porch rails and replaced the screen door and let the walls remember laughter that wasn’t pretending to be okay. We made new rules. Real family protects; it doesn’t manipulate. Real family looks you in the eyes and tells you the truth even when the truth is expensive.

If you’ve ever had to cut out a toxic branch to save the tree, I see you. If you’ve ever said enough, I hear you. If you’re still gathering the courage, borrow mine. Blood is not a license. It doesn’t entitle anyone to break you.

And if a man ever looks at you after emptying your accounts and says he needed it more, I hope you look him in the eye and let your voice find steel.

Then I hope you let the door open and the badges in and your future back in your own hands.

If you want the unvarnished truth, here is what the rest of that day looked like from the inside out. After the officers took Kyle through the doorway he had barreled through all weekend like a parade float, the air did not immediately turn sweet. It carried the metallic residue of adrenaline. Aunt Patricia reached for a dish towel and smoothed it with her palm the way you smooth a child’s hair. Uncle Robert stepped onto the porch and stood with his back to the rail as if he had stationed himself on a quiet ship whose job it was to keep watch for storms he could not let inside. Emma washed the two coffee cups Kyle and Allison had left on the counter with a care that bordered on reverence, as if the act of cleaning could rewrite the morning.

Detective Harmon stayed. She spread her notebook on the table and asked if I needed water. My throat was dry enough to splinter but I said no because saying yes felt like asking for help and I wanted to remember I could still stand up by myself. She took my statement with the steadiness of someone who has sat with people in the middle of their earthquake and knows which questions do not make the ceiling fall. She asked me to walk her through every step from the previous night—when I saw the cord in the wrong port, when the login alert hit my phone, when I changed the passwords, when the transfers registered on my account. I gave precise times because my body had been checking the clock like it was a shore.

“Do you want a restraining order as a temporary measure?” she asked. The word temporary did something kind in the air. I nodded. She explained the process in simple, sturdy sentences. File at the county courthouse. Emergency order today. Hearing later. I signed where she pointed. It felt like sweeping glass into a dustpan—still sharp, still dangerous, but contained.

Allison sat at the edge of the kitchen table, small in a chair that had never made anyone look small before. She stared at her hands until the words unfroze. “He told me it was a short‑term loan,” she said, and the syllables tripped over one another like they had to get out before they could be forced back in. “He said he had an opportunity—something about a bridge, a flip, a sure thing—and that he’d put it back before anyone knew. He said you’d make it back in a month anyway because you’re ‘good at sales.’ He said…he said I owed him faith.”

Emma reached for her. Allison flinched on instinct and then let herself be held. There are moments when survival looks like allowing touch.

I signed the last form. Detective Harmon left numbers on a business card and told me I could call any time, day or night. When she stepped out, the room did not collapse. It breathed. We could hear the lake again. We could hear our own voices at the levels human beings were meant to speak.

Emma walked me down the hall to the small bedroom because motion helps a body accept what it already knows. I pulled the suitcase back out, checked the laptop, checked the app logs again even though I did not need proof anymore; it was a ritual, not a necessity. The photos were there: the angle of his jaw in the glow of my screen, the curve of his shoulders as he leaned over what he thought was a private moment with a machine. The keystroke record captured the answers to my security questions, each letter typed with the casual cruelty of certainty. The IP address matched the router at the lakehouse. Facts can be a soft blanket and a sharp blade. That morning they were both.

I called Claire from the bedroom with the door closed and told her the headlines I could tolerate saying aloud. She passed through anger, disbelief, and then logistics in under a minute because she is the kind of person who can keep three tabs open in her heart without any of them freezing. We mapped immediate triage. Freeze any cards linked to the business, even if the accounts were already at zero; fraud protection often requires you to perform what should be redundant. Call the bank’s fraud department again and again until a human with power answers; get case numbers in writing, not just over the phone. She would be at the store by nine. She would meet the morning deliveries. She would frame a sign for the window that said, with the clean courtesy of a well‑run operation: We’re open. Thank you for your patience.

By noon the house had moved into a version of normal that felt like walking on foam. The family made lunch. Allison helped slice tomatoes and flinched only once when a knife clicked against the cutting board like a door closing. We took bowls out to the porch and ate with the kind of appetite you have when your body demands fuel for the administrative labor of surviving. No one filled the empty chair. The lake existed for us like a promise we didn’t have to cash yet.

In the afternoon I sat with my back against the bedroom door and did the math you do when a storm has ripped off part of your roof and you have to decide whether to tarp or rebuild. Fixed costs. Payroll. Orders already placed. Deposits that could not be lost without losing reputation. We could float for thirty days with the reserves in the separate operations account that Kyle had not reached. The second location’s landlord had been promised a cashier’s check by Monday; I called, told the truth without apologizing for the truth, and asked for forty‑eight hours’ grace. He gave it because people will when you give them the dignity of being needed for their decency.

That night I slept for ninety minutes in two pieces and woke with a headache like a tight hood. Morning came as it always does, indifferent and useful. We packed the cars. Uncle Robert made three trips because he cannot leave people half helped. Aunt Patricia folded the towels in precise thirds in the way she has always believed keeps chaos at bay. Emma, practical and tender as always, slipped grocery store gift cards into Allison’s coat pocket without saying a word. We locked the lakehouse and the sound of the hasp catching felt ceremonial.

Driving back to Portland, I made two phone calls I did not want to make and one that I did. The first to the bank’s fraud investigator assigned to my case to answer the questions he asked slowly and in the same order he had yesterday because protocol is a shelter that stands up in the rain. Yes, I knew the suspect personally. Yes, he had physical access to my devices. Yes, two‑factor authentication had been enabled after the initial attempt but before transfers occurred; here was the log showing when. The second to the insurance carrier for my business policy, because the clause that sits in the fine print like a sleeper car on a train would wake up only if I pulled the cord with the right words. The third to Claire, who told me she had brewed a second pot of coffee at the store and that three regulars had left notes by the register: We’re with you. Open when you can. We’ll be back.

Grief is not just for the people we lose. It is also for the versions of our lives that are taken by someone else’s hunger. I cried in the car on I‑5 once, not because I am weak, but because my body needed to release enough salt water to taste like the ocean again and remember I am part of something bigger.

Back in the city, the practical work began to look like ritual. I printed every log, every screenshot, every transaction record and slid them into a binder with tabs—Bank, Police, Insurance, Store. I made copies. I labeled the spine. This was not busywork; it was architecture. If you build enough order, sometimes chaos gets bored and leaves.

Allison arrived at my apartment that evening with a duffel and a cardboard box that said Kitchen in black marker though it held only a framed photo of us at twelve and sixteen in front of the hardware store. She stood in the doorway for a long second and then she walked in. The walls did not care who she had been married to. The couch did not care what she had apologized for that was not her fault. I set the box on the table and we sat.

She did not confess so much as unfurl. Control does not always look like shouting. Sometimes it looks like a man who makes everything expensive even when it is free. He had tracked her phone “for safety,” then criticized her for “wasting gas” if she took the long way home. He had opinions about what she wore, couched as financial advice, which is how you make a cage look like a calculator. He had methodically eroded the surface of her friendships the way a river erodes a bank—one comment, one discouragement, one manufactured crisis at a time. He had taken her password “just in case” and then, like a man tasting an apple that was never his, taken mine when he thought her trust should extend to every corner of her life.

We ate rotisserie chicken with our fingers because forks felt like too much formality. We watched a movie we could half ignore. At midnight I made up the spare room with sheets that smelled like detergent and the lemon of the closet sachet. Allison lay on her side and stared at the wall as if it could teach her something. Sleep took her anyway.

The next week carried the shape of a new habit. Morning at the store with Claire, afternoon in meetings that involved the remarkable dullness of resilience. The fraud department called with incremental updates. The bank placed a hold on the destination account before the funds could fully vanish into the nest of smaller shells Kyle had been so proud of describing to men who liked to nod. The case numbers accumulated and began to look like pillars. The landlord for the new space accepted the cashier’s check on Wednesday. We signed. The pen felt heavier than a pen.

I did not scream or throw things or act like the movies taught us to act when rage is justified. I bought paint. I rolled Mitchell Blue on a test patch of wall and stepped back and cried a little because sometimes a color can feel like a parade thrown for the version of you that did not quit when quitting would have been easier. Claire arranged the racks in exact increments so the flow of bodies would feel like choreography when the door opened. We assembled the dressing room mirrors and then assembled ourselves when a screw fell and pinged across the floor like punctuation.

Allison found a part‑time job at a grocery store ten blocks from the apartment because she wanted to earn money that had no strings. She took classes at the community college two nights a week. She drank water again. She ate breakfast. She texted Emma without asking anyone’s permission. The light returned to her face slowly, like dawn in January.

On a Tuesday afternoon, Detective Harmon called to tell me the District Attorney’s office was filing charges—fraud, identity theft, coercion. “You may be asked for a victim impact statement,” she said, and the phrase sounded both clinical and merciful. She explained that a guilty plea would mean I wouldn’t have to testify at a full trial. I thanked her for explaining the landscape before letting me walk across it alone. When we hung up, I stood very still in the back room of the shop and felt the weight of a life that had been put back into my own hands shape by shape.

When Kyle pleaded guilty, the courtroom did not look like television. The fluorescent lights were indifferent. The wooden benches had been sat on by every kind of person who ever needed a system to do its job. The judge read words into the record that sounded both ceremonial and practical. Kyle’s attorney did the thing attorneys do when the facts have become stones and there are only so many you can step on without sinking. Allison sat on the edge of the bench beside me, shoulders straight, eyes forward. When the hearing was over, she did not look back. That was not defiance. It was the art of choosing where to place your future.

Opening day at the second location produced the kind of joy that makes you aware that joy has a body—it has breath, it has temperature, it takes up space. The bell over the door rang like a favorite song. A woman came in wearing a coat that had belonged to her mother and asked if we had anything that could make her feel like herself again after a hard winter. We did. Claire wrapped her purchase like we were sending her out under a blessing. The two new hires—smart, kind, particular—moved like they had been standing behind that counter for months. We met our numbers by two o’clock and stopped checking because hitting targets is wonderful and not having to worry is better.

At night in the apartment, Allison and I cooked. Chopping vegetables with her felt like returning to a dialect we had always spoken but had forgotten we were fluent in. She told me one evening, her knife pausing over a carrot, “You were brave for protecting what you built, Becca. I want to be brave enough to rebuild myself.” I told her rebuilding is not a single act; it is the way you stir soup and wash a plate and send an email and choose sleep instead of scrolling because rest is also a kind of courage.

Sometimes we would sit on the fire escape with mugs of tea and talk about our parents, not the sainted version that grief makes when it wants to be tidy, but the real humans who argued about whether to replace the store’s front awning in October or wait until spring, who sometimes ate dinner standing up, who taught us that work is a four‑letter word you can say with love.

On a Saturday morning when the new store had been open a week, we drove to the lakehouse. It was early enough that the road belonged to delivery trucks and joggers. We stopped at a hardware store on the way to pick up paint trays and rollers because I will always prefer to buy a tool in person and hold it in my hand before it becomes part of the solution. The screen door creaked when we arrived—the exact creak our father used to promise he would oil and then never did because some parts of a place are allowed to sound like themselves.

We worked in companionable silence. I taped the baseboards. Emma cut in the corners with a wrist that has clearly been loved by paintbrushes. Allison took the wide strokes and left them neat. We sanded a step that had nicked the same shin for twenty years. We tightened a loose kitchen drawer pull. We opened the windows and let the place breathe. The day slid by and at four we stood on the porch rail and looked at our work the way you look at a photograph you didn’t know you would ever have again.

Then we made rules. We did not write them down because the point was to act them, not frame them. Real family protects; it does not manipulate. Real family asks before it uses; it does not take and call it borrowing. Real family sits at the table and tells the truth even when the truth is expensive to say. Real family accepts help and offers it and understands that both are forms of grace. Real family knows when to lock a door, not to keep love out, but to keep harm from walking in like it pays the mortgage.

If you’re reading this and waiting for the part where I say forgiveness came like a white flag—I don’t have that for you yet. Forgiveness is not a one‑time wire transfer. It is a payment plan and sometimes a pause. I do not owe anyone a timeline. What I owe is the decision not to let bitterness become the landlord of my days. Some mornings I practice by wishing Kyle exactly what he earned from the universe: consequences, distance, the chance to be a better man later than he should have been. Other mornings I practice by not saying his name at all.

And if you are somewhere in your own story at the moment right before the door opens and the badges enter, I wish you the courage to trust your evidence and your instincts. Put a bell on your front door and your heart. Listen for it. Build a binder. Make copies. Tell the truth. Ask for the temporary order that keeps danger from mistaking proximity for permission. Call your cousin who has always kept an extra key to decency. Stand on your own porch and breathe air that does not ask you to apologize for needing it.

I do not believe the universe balances its books with poetry. I believe people do. We balance by being exacting with ourselves and generous with one another. We balance by noticing when a charger sits in the wrong port and when a woman looks smaller than a kitchen chair should allow and when a family rule has to be rewritten because the old one made room for harm. We balance by setting the table and making enough for one more and also by saying, with love, that some people do not get a plate right now because they have confused hunger with entitlement.

The blue on the shop’s front door looks different in late afternoon—the pigment thickens, the hue quiets, the color says home with its inside voice. Customers hold the handle that we installed ourselves, and the small bell rings, and commerce happens the way it is supposed to when everyone shows up honest. Allison comes by after class some evenings and sits on the bench by the window and does her homework while I match stock to hangers. We close at six. We sweep. We lock the door. We walk home.

I dream sometimes that I am back at the lake, nine years old with a jar of screws. I sort them until every size sits with its own kind and then I tip the jar back into one pile because the point is not to create compartments, it is to remember that you can bring order whenever you need to. I wake up and the city is quiet for a beat and then it is not. I put my feet on the floor and choose again.

The day will come—maybe it already has—when this will be a story I tell to a new hire who asks why we stamp the date on the back of every alteration ticket and initial it. I will say: because precision is how we keep each other safe. I will say: because somewhere a woman is checking her account balance and learning something about someone she loves that she will spend a year unlearning. I will say: because generosity without boundaries is not kindness; it is a clearing where wolves wander through.

If I could go back to the moment in that kitchen when Kyle said, “We needed it more than you,” I would not say anything different than what I said. The line I spoke then—Then you won’t mind what’s coming next—fit like a key finally meeting the lock it was cut to open. I might, however, add one thing to myself in that moment, a sentence spoken silently the way you tuck something into your pocket before you walk into the weather: You already have everything you need to survive this. Use it.

And then I would watch, again, as the door opened and the word Police cut the air, and I would remember how it felt when the future walked back in on its own feet.

Some stories end with a wide shot. Mine ends closer. With the sound of scissors sliding through tissue as Claire wraps a dress, the registers closing with their tidy snick, Allison humming in the doorway backlit by a sky that knows rain but isn’t delivering it today, and the bell over the door ringing, ringing, ringing, every time someone comes in looking for something that will fit, and finds it.

There is a part of this story I have not told yet because it is quiet and unremarkable in the way that most real rescues are. It is the afternoon the bank investigator called to say the provisional credits had become permanent and the account balances you see on your screen are the ones that will remain. I did not shout. I did not throw my hands in the air like a halftime show. I sat on the office stool in the back of the second shop with a roll of tissue paper under my palm and said, “Thank you,” as if I were being handed a glass of water. Ninety‑seven percent. The remainder protected. Numbers that finally matched the truth I had been busy living toward.

After that call I walked the length of the store slowly, hand on hangers as if greeting a row of friends. Claire asked if I needed a minute. I told her I needed a broom. We swept the floor we had already swept that morning because some satisfactions are best when repeated.

There are no new plot twists here. No secret benefactor. No cinematic montage with a new soundtrack. Only the next right thing, performed until it becomes muscle memory. We installed a password manager and made the kind of passphrases you cannot memorize on purpose. We set up hardware keys and tucked the spares into a safe that clicks like a vault even though it is not one. We changed the Wi‑Fi name from something casual to something neutral and long. We turned on alerts that had been available for years and ignored because no one wants to live as if the worst is waiting. We did not make ourselves scared. We made ourselves ready.

In the evenings, once the racks were straight and the register counted down and the glass cleaned with the circular motion that yields no streaks, Allison and I would walk the two blocks home and talk in the kind of detail that therapy eventually teaches you to use with yourself. We did not label or diagnose. We described. The particular shade of quiet that settles on a house when one person’s temper requires everyone else to watch the weather. The precise way a compliment can be used to erase the memory of a wound. The odd relief and grief that arrive together when a habit you mistook for love stops appearing in the doorway.

One night I wrote my victim impact statement at the small kitchen table with a pen I trust. It did not sound like a manifesto. It sounded like a balance sheet that refuses to lie. I wrote about time—the hours spent on hold, on forms, in lines; the mornings not waking in my own mind but in a map of tasks an injury made necessary. I wrote about sleep—the weeks of it coming in pieces and at the wrong times. I wrote about staff hours reassigned and marketing delayed and inventory staggered so cash flow could be a bridge instead of a wall. I wrote about standing in my own store feeling like a guest and then feeling like the owner again. I wrote about Allison, and the day she used her own keys to come home to a place where no one asked to see her phone.

I did not submit it hoping it would change the sentence. I submitted it because naming damage is a way to stop it from pretending to be something else.

Uncle Robert came by the shop one afternoon carrying a small box that used to hold drill bits but now held a sandwich, an apple, and two napkins folded the way my mother used to fold them. He did not say I’m sorry again because apologies, like compliments, lose their edge if you drag them over concrete too many times. He told me a story about my father instead. About the first time a contractor shorted the store on a pallet of siding and how my dad drove the delivery truck back himself and walked into the warehouse with a receipt, a tape measure, and that particular brand of politeness he wore like a uniform. “He never raised his voice,” Uncle Robert said, “and they never shorted him again.” We ate in the back room on upturned milk crates and I realized that the inheritance that matters fits in your mouth and your hand and your posture when the world tries to make you smaller.

On a Wednesday during the first month after opening, a woman came in with a dress that had belonged to her sister who had died in February. She wanted the hem lifted and the sleeves softened. She wanted to wear it to a job interview because her sister had always believed in her. We pinned and chalked and I stitched the seams myself that night after close. She came back on Friday. When she put it on in the dressing room and turned to the mirror, she cried quietly for twenty seconds and then smiled in the way people do when a piece of clothing has become a permission slip. I did not tell her anything about betrayal or recovery. I told her she looked prepared. She left with the kind of posture that is contagious.

Allison’s classes began to leave the calendar and enter her life. She worked morning shifts at the grocery store where regulars learn your name by learning your face first. She studied in the evening. She printed notes and underlined and brought me questions that had less to do with punctuation than with courage. She said, “What if I’m not the kind of person who finishes things?” I said, “Look at this apartment. Look at this shop. Look at this sentence. Finishing isn’t a kind of person. It’s a series of decisions you protect.” She nodded and set her alarm.

If you came to the lakehouse the next month you would have found a porch that no longer peeled and a screen door whose friction had been sanded until it sang instead of shrieked. You would have found a kitchen drawer that no longer stuck at forty percent. You would have found three women standing on ladders at reasonable heights because risk management is a love language too. You would have heard Uncle Robert declare that the dock planks were finally “respectable,” which in his dialect is a word that means both safe and handsome. You would have smelled coffee and lemon oil and the ghost of cedar.

The rules we made there are not etched on a plaque. They are in service. Allison takes the first sweep of the porch without being asked. Emma refills the ice trays because she understands how tiny mercies multiply. I order the bulk paper towels and never let us run low. Aunt Patricia sits in the shade with her ankles crossed and tells us old family stories, and when she reaches the part that hurts, she pauses and drinks water instead of pretending she’s fine. We practice, in mundane ways, the fact that love is a verb that keeps choosing.

On the day the sentence came down—a date circled on my calendar in blue ink because I wanted my memory to file it under sky, not storm—we did not go to the courthouse. There was no dramatic confrontation needed, no statement to deliver in a room where fluorescent lights wash everyone the same color. A short email arrived from the Victim Services coordinator with a PDF attachment and a line that read, “We wanted you to know.” The number of years mattered and also did not. What mattered was the period at the end of the sentence. What mattered was Allison exhaling in a way her body had not dared to try for a very long time. We went to the lake that weekend and grilled vegetables and ate them off paper plates because sometimes the right ceremony is the one with the fewest dishes.

If you are waiting for a scene where our family gathers and says everything right in the right order—no. What we do is better and more honest. We sit on the porch and let the sun go down at its own speed. We do not pretend the past is a movie we can edit. We do not borrow trouble from tomorrow. We take turns washing the bowls. We leave the screen open to let the air move. We tell the truth about what the truth cost and what it gave back with interest.

The shop keeps teaching me things I didn’t come here to learn. A well‑made seam can carry weight you would not expect by looking at it. People are more loyal to honesty than to perfection. The bell over the door rings at different volumes depending on who is holding it, and some days the softest rings are the ones that carry the most news. A small business is an ecosystem, and so is a family, and the health of either depends on what you do when something invasive tries to take over the soil.

When customers compliment the front door color, I tell them it’s Mitchell Blue and they smile like I’ve told them a secret. The truth is that the door is the first promise we make and the last thing people touch when they leave. It matters that it feels right in the hand. It matters that the paint doesn’t chip at the corners. It matters that the key turns smooth at close because closure, literal and otherwise, is a craftsman’s job.

Some nights, after Allison has gone to bed and Claire has texted the next day’s schedule and I have checked the alarms and set out the bank deposit for the morning, I sit in the dark with the window open and let the city be a city. Sirens move through and somewhere they are a disaster; here they are simply proof that the system still spins its wheels when asked. I think about the two hours between the sentence I spoke—Then you won’t mind what’s coming next—and the moment the police cut the air in two. I think about how thin a bridge can be and still hold. I think about how many women I know who have had to learn to be their own witnesses. I think about how ordinary the acts of saving ourselves often are.

I will not rewrite the past to make myself more prescient or more naive. I will not pretend I saw every move coming. I will not pretend I missed all the signs. Both things can be true: I was careful, and it still happened. I hardened the surface of my life where I could, and someone found a soft spot. I left the lakehouse with less in my accounts and more in my hands.

You can trap a person with better manners and you can free a person with better habits. I keep a binder now. Not because I am afraid, but because it is easiest to rescue a future you have prepared for. I teach the new hires to stamp dates and initial alterations not because we expect conflict but because we respect accountability. I ask Allison, before we leave the house, “Do you have your keys?” and she answers yes and shows me the small ring she picked herself. It is not infantilizing; it is generative. We build rituals to anchor ourselves so that when trouble tries to make the room spin, we can find the floor.

One year after the lakehouse weekend, we stood on that same dock and watched the water hold the sky without spilling. The porch rail needed only a quick touch‑up. The drawer still glided. Uncle Robert declared the dock respectable again because repetition is sometimes the soul of faith. Emma brought iced tea in jars like we were in a magazine spread about plain good sense. Aunt Patricia told the story where I sorted screws into sizes and Allison named a rock Passport, and we all laughed at the timing of memory: how it can deliver the one you need right when you need to remember who you have always been.

What did justice look like, finally? It looked like my accounts reflecting the work they were meant to fund. It looked like Allison reading a syllabus at the kitchen table and highlighting dates without anyone asking her why she needed highlighters. It looked like Claire taking two days off because we finally had the margins to let rest be part of the business plan. It looked like the bell over the door ringing at 10:02 a.m. and again at 10:07 and then for the rest of the day at a pace that told me we would make payroll and then some. It looked like the lake holding our reflections steady enough that we could recognize ourselves again.

I would be lying if I said bitterness never comes around asking to borrow sugar. It does. I answer the door, look it in the eye, and say no. Not today. I have a shop to run. I have a sister to root for. I have a dock to repair in September. I have a color to keep from chipping. I have a list of tiny tasks that, collected, constitute a life.

If you are here because something was taken from you and you are trying to decide whether to believe in systems again, I cannot make promises for the parts of the world I do not run. I can tell you that the day I needed them, the bank did what the bank was supposed to do, the detective did what a detective is meant to do, the law did what the law had been asked to do for once on behalf of someone who does not have a corporate legal department on retainer. I can tell you that calling sooner is almost always better. I can tell you that you are not overreacting if your hands shake. I can tell you that you are allowed to be both furious and methodical. The combination is, in my experience, effective.

As for Kyle, his absence is not a character in our house. We do not check the mail for his name. We do not Google his facility. We do not count months. We make dinner. We do laundry. Allison studies. I pay invoices. Emma texts me photos of paint samples for the guest room at the lake. Uncle Robert sends a weather report before he leaves the city as if the lake might argue with the forecast. Aunt Patricia tapes recipes to the inside of the cabinet door. The world moves. We move with it.

Sometimes I think about the sentence he chose: We needed it more than you. Need is a word that should be handled like a blade. It can cut you free or cut you open. He used it as a saw. We use it as a scalpel. We need air and water and safety and work that does not make us small. We do not need someone else’s something because we have decided not to do the slow, dignified labor of making our own.

On closing nights I turn the key in the blue door and the bell gives one last ring. It sounds like a promise and a benediction. It sounds like the first day and the last line of a chapter. It sounds like a life that is not waiting for permission to be protected anymore.

So here is the end, plain and earned: After our family reunion, I checked my account and it was drained. My brother‑in‑law snorted that he needed it more. I told him he wouldn’t mind what was coming next. Two hours later, the door opened and the police came in and the future found its way back toward me. A month later, we opened the second shop. A year later, we stood on the dock and counted the ways we had refused to break. Today, the door is blue, the bell is faithful, the work is honest, and my sister is free.

Blood alone does not entitle anyone to your labor, your safety, or your peace. If you needed someone to say it out loud so you could start building the next part—here I am, saying it. Build. Lock the door at night. Answer when opportunity knocks. Tell the truth even when it is expensive. Sweep the same floor twice if it helps. Stand where the light is good. And when harm tries to walk in wearing family’s shoes, look it in the face and say, with all the steadiness you can find: Then you won’t mind what’s coming next.