I heard the crack before I felt it—a bright, brittle snap like a winter twig under a boot. The corner of the dining table found the soft place beneath my ribs and the room went white around the edges, the way light looks when you stand too quickly. My sister’s breath washed over me, warm with wine and peach shampoo. She was still yelling about a shirt, a nothing, a small thread she’d pulled until the whole fabric gave way. I tried to breathe the way I always had—thoughtlessly—and air turned into a narrow doorway that kept closing.

I pressed my palm to the floor to find something stable. The wood felt cool and ordinary. Ordinary helped. I reached for my phone because habit moves faster than hurt. In America, three numbers live under your skin from childhood: 9-1-1. The promise is that someone answers. The promise is you won’t be alone.

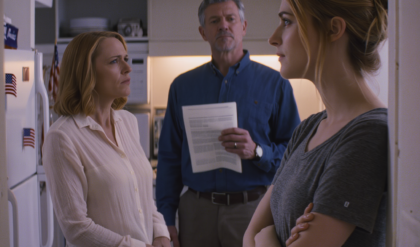

My mother entered like a forecast you’ve learned to fear—hard step, hard hand—and plucked the phone from my grip before the third digit landed. “It’s just a rib,” she said, as if she carried an accurate map of me. “You’ll ruin your sister’s future over this?”

The word future fell between us like a locked door. My father filled the doorway with the frown he saved for spills, bills, and me. “Stop being dramatic, Anna. You always exaggerate.” Even the way he shaped my name sounded like a charge.

I stood slowly, as if I were persuading the house to hold still. Something inside me shifted that wasn’t bone. It was older, smaller, slipperier—a latch I hadn’t known I was allowed to lift. I slid one arm into my jacket and left the other sleeve hanging, a flag of concession to physics, and walked past them. No one reached for me. My mother kept the phone. My father kept the look.

Outside, the sky was the color of clean dishes. A flag across the street lifted and fell in a lazy rhythm. Somewhere a rake scraped concrete, back and forth, collecting a neat pile of things that had fallen without asking permission. They called my name the way you call a dog that has learned not to come. I didn’t turn.

The emergency room wore its own American brightness—bleached floors, walls the color of paperwork, a television lip‑reading football, the medicinal insistence of antiseptic drifting over coffee gone long past good. At triage, a nurse with steady eyes asked about my breathing. I told her it felt like shoving a stubborn drawer closed over and over. She clipped a pulse oximeter to my finger and watched the numbers settle into something that didn’t frighten her. A wheelchair appeared as if conjured. I learned how to sit without looking like I was falling.

Radiology was colder. The tech slid plates beneath me with the cautious gentleness people use for sleeping children. Hold it. Don’t breathe. Breathe. Again. The machine hummed like a refrigerator in a quiet house. I stared at the perforations in the ceiling tile and thought of the stickers my sister and I hid under the kitchen table when we were small—gold stars for chores, smiley faces for not fighting. Hers stayed where she stuck them. Mine curled at the corners and fell.

The doctor returned with films and a capped pen. “Two fractures,” she said. Hearing it was a verdict and a relief, like being told the storm you’re in has a name. Pain had a picture. “We’ll manage pain. No binding—outdated. Breathe deep even when it hurts; it protects your lungs.” She spoke in a tone that didn’t ask me to agree.

At the discharge desk, a nurse slid a clipboard toward me. The pen was tied with a length of blue string like a boat at dock. She lowered her voice without turning pitying. “There’s also this. Would you like to file a report?”

My mother’s sentence circled like a hawk: You’ll ruin your sister’s future. In our house it had become unwritten law, muscle memory dressed as virtue. Another sentence rose beside it, small and solid: What about mine? I was twenty‑four, working mornings at a coffee shop and afternoons at a bookstore, saving each dollar that didn’t already have a job, counting weeks in rent and bus fares and the price of a secondhand couch. None of those plans included living as a target.

“Yes,” I said. The word arrived steady. “I want to file a report.”

The officer who came wore a vest with his last name stitched above the pocket and the posture of someone who has done this too often to be surprised but not so often as to forget how to be human. He asked what happened, where, and when. He didn’t ask why I hadn’t called sooner. He took photographs and told me why the angles mattered. He wrote. He listened. He handed me a card with an advocate’s number scrawled across the back in block letters a tired person could read. “They can help with next steps,” he said. “If you want a restraining order.”

By the automatic doors, my phone lit up like an accusation. A missed call from my father. A voicemail full of my mother’s wet, practiced grief. A text from my sister: You’re dead to me. I turned the screen face down and studied the scuffed track the wheelchair wheels had cut across the floor. It looked like a road.

I went to a friend’s spare room with a small bag and the manila envelope the hospital had given me. The mattress on the floor smelled like laundry and a little like sun. The walls were the color of unasked questions. I lay down the way you lower a fragile thing into a box and discovered there’s a right way to cough. Breathing turned into work I scheduled. I set alarms to remind myself to do it.

The advocate called in the morning. Her voice carried that particular steadiness of people who know they can’t save you but can stand in a good place while you save yourself. “We can file for a temporary order today,” she said. “Bring your ID, the hospital paperwork, and patience. I’ll meet you at the courthouse. I’ll talk you through where to stand and what to say.” She described the hallways and the window and the door and the exact position of the judge relative to where my shoes would be. She didn’t promise ease. She promised process.

The courthouse smelled like coffee, paper, and the metallic patience of elevators. A seal hung over the bench; a flag dozed in the air‑conditioning until someone opened the door and made it move. We stood in line with other people turning their lives into forms. When the judge asked for my name, my voice surprised me by arriving on time. The order was granted with a stamp and a date. It felt like a small fence where there had been a field. I held the paper and felt something in my chest tilt toward open.

That night the calls returned, a duet of reputation and guilt. “We are a family,” my father said, as if the noun itself were a contract I had violated. “Families do not call the police on each other.”

“Families don’t break bones,” I said. I did not garnish the sentence with apology.

My mother cried like performance turned habit. “You’ll ruin her life.”

“She almost ruined mine,” I answered, and ended the call.

Borrowed rooms have their own quiet. It isn’t safety yet. It’s shelter. I learned to sleep flat, a pillow under my knees and another under my arm. I braced my chest when laughter surprised me. Pain became a map: this movement, that ache; this breath, that sharp protest. I wrote myself instructions on my phone: Deep breaths every hour. Ice twenty minutes. Do not twist to reach the outlet. Nap when the ache sours your temper. Be kind to the floor.

Work bent around healing. At the coffee shop, my manager shifted me from lifting to the register. I wiped counters and made change and learned which regulars wanted weather and which wanted quiet. At the bookstore, I traded boxes for displays, stacking memoirs written by people who refused to disappear into other people’s stories. I built a table about endurance and kept returning to straighten it, the way fingers find scars without meaning to. A child asked where the dragon books lived. I pointed. He nodded like I’d handed him a key to a small republic.

At night, I wrote. Not anything grand. Evidence I could point to when the old story tried to take the microphone. The exact shape of the doctor’s “Two fractures.” The way the officer explained photographs like he was teaching me to see with two eyes at once. The taste of the first pill with water. My mother’s breath between words. The click the door made when I left.

The hearing for the longer order came a month later. I wore a clean shirt and flat shoes and a face that did not apologize. No one from my family came. Absence can take up a whole bench. I sat with mine and tried to let it be a chair, not a cliff. The judge asked me to confirm details. I confirmed them. He read the order in the same voice he’d used to approve a name change for the person before me, stamped, signed, and slid the paper forward. It was done because the law said so, not because anyone believed me more today than yesterday, and that steadiness steadied me.

Outside, the courthouse steps held late sun. People lived regular lives on the sidewalk. I felt ordinary, and that felt better than triumph.

I returned to the house with a police escort to pack. The kitchen smelled like lemon cleaner and something we’d been pretending was air. My mother stood at the sink and told the officer it was a misunderstanding. He nodded without agreeing. I folded clothes the way you fold difficult days—carefully, with the respect you wish had been used on you. I took shoes, a handful of books, the framed photo of me at graduation where the smiles looked practiced, the small wooden box my grandmother once pressed into my palm without explanation. In the hall, my father leaned on the doorjamb. “Do you feel powerful now?” he asked, managing to make power sound petty.

“No,” I said. “I feel ordinary. That’s the point.”

The apartment I found was small and bright, secondhand in the ways that make a place honest. A thrifted couch with unfamiliar pennies under the cushions. A table that wobbled until I learned where to press. Mornings with quiet that didn’t feel like punishment. The first night I slept there, I woke at dawn and listened to the building’s pipes begin their day. I stood in the kitchen with my palm over the healing line of bone and felt the astonishment of being the only witness I needed.

Therapy was a room with a soft chair, a box of tissues I didn’t touch, and a clock with a patient sweep. “What did you learn you were for in your family?” the therapist asked.

“To absorb the blast,” I said, surprised by how quickly the answer arrived.

“And anger?”

“Hers was weather. Mine was danger.” The words sat between us like salt and water—simple elements, necessary, stinging where they touched the wound.

We laid out the old script like an outfit that no longer fit: your sister’s temper is inevitable; your silence is love. We practiced new lines until my tongue stopped tripping: My safety matters. Saying no is not cruelty. Boundaries are not punishment. Forgiveness is not bleach. Clarity is enough.

The support group met in a church basement that smelled faintly of coffee and old hymnals. We sat in a circle on metal chairs that complained under every shift, and we learned to say things in the simplest words. Simple is not easy. We practiced letting silence do some of the work. We made lists of what safety looked like, and no list matched another. When someone cried, no one rushed. When someone made a joke, we let it live or die on its own. We weren’t a chorus. We were a room full of people building separate houses with a shared pile of lumber.

On the bus home, I watched the city pass and realized I could sit without bracing my arm across my chest. I watched a man tie down a ladder on a truck like he was securing a small bridge. I watched two teenagers pretend not to hold hands. I watched a woman carry a sheet cake as if America itself depended on her not tripping.

My parents didn’t call for a while. Then my mother appeared at my door six months after the break. I left the chain on. She looked older, the way people do when they’ve been hauling a story that no longer carries them. “She’s struggling,” she said softly. She didn’t need to say my sister’s name. “She needs help. We all do.”

“I hope you find it,” I said. My voice felt level under my feet.

“Can I come in?” she asked.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea today.”

“You were always stubborn.” It used to sting; now it landed like weather on glass.

“I learned it from you,” I said. Surprise crossed her face like a cloud. She took her hand off the door one finger at a time, as if the metal were hot. She didn’t argue. She turned and left.

I made tea and stood at the window. The block wrote its evening poem—bus brakes sighing, a dog insisting on one more corner, a small flag over the hardware store lifting when a car passed. Peace didn’t announce itself. It seeped in like water finding a crack and kept going until it pooled.

The nightmares still came sometimes, habits with nowhere else to live. I kept a glass of water on the bedside table and a note that said: You are in your apartment. The door is locked. Morning will come. When I woke with my heart too loud, I read it and breathed the way the ER handout had taught me—slow in, slower out. The ache lost its teeth. Pain turned into weather again.

I learned the city slowly and with attention. The bus that arrives late and then two at once. The corner store clerk who began using my name. The exact minute the sun finds my window and turns the cheap glasses into church. The smell of rain in hallways where people are kind because we share thin walls and our noise fits together whether we mean it to or not. I learned what hunger feels like when you answer it with food you chose. I learned the shape of a day in which nobody waits to tell you what you owe.

At the coffee shop, I returned to lifting milk crates without seeing stars. At the bookstore, I started running the events calendar, writing small author bios that were really love letters disguised as logistics. People stood in the aisles like you stand in old churches—shy, reverent, hungry for permission. An author with a quiet laugh told a girl in a denim jacket, “Your story is already good. The work now is to make it true.” That night I slept through.

Sometimes I caught my reflection and didn’t recognize the set of my shoulders—neither braced nor bowed, just ordinary. The first time I laughed hard and my ribs didn’t complain, I sat down on the sidewalk because joy felt ceremonial and I didn’t want to do it standing up. A dog paused to observe me and then, satisfied I wasn’t a threat to the neighborhood, trotted on.

On a Sunday, I emptied my keepsake box onto the table. I kept the letters and photos and the ticket stub from the first concert I went to without asking permission. I ripped up a list I’d titled years ago WAYS TO MAKE THEM LOVE YOU. Four pieces for the four of us, then more, because tidy symbolism is pretty but life resists pretty. I put the box back under the bed. Not every story needs display space. Some get to live quietly.

Because I am still American enough to love a ceremony, I bought a grocery‑store cake. The teenager behind the counter wrote CONGRATS in careful, uneven icing. I carried it home like a fragile instrument, cut a slice at my little table, and ate it with a fork from the thrift‑store set. It tasted like sugar and intention. In the chair by the window, a cat from the building across the alley watched me with the suspicion of someone who has seen too much. “It’s for me,” I told the empty room. The empty room agreed.

At the year mark, I renewed the order. Not because I was still scared every day, but because I’d learned I could ask the world to help me guard my life and the world—represented for the moment by a clerk with a stamp and a capable smile—would say yes. That yes tasted clean.

I ran into my mother in a grocery store aisle where the cucumbers look like they belong to people with plans. We did the cart dance people do when they don’t want to collide. “You look… good,” she said, testing the word for strength.

“I am,” I said.

“She’s in a program,” she offered. Program covers a lot of ground—treatment, course, attempt. “We’re trying.”

“I hope it works.” Hope doesn’t require reunion. It doesn’t require conversation beyond this.

She reached as if to touch my arm, then let her hand fall. “Take care of yourself,” she said.

“I am,” I said. “I will.”

We rolled on like ordinary shoppers. The automatic doors opened and closed. Outside, a flag lifted and fell in a wind neither of us controlled.

Walking home with a small paper bag, I considered the sentence they’d given me the day my ribs broke: You’ll ruin your sister’s future. I said aloud to the quiet block and the sycamores and the slice of sky, “I am not responsible for anyone else’s future,” and because I believe in marking occasions, I added, “Amen.” I laughed when my ribs didn’t argue.

That night I changed the sheets, opened the window a crack, and listened to the building breathe. Somewhere above me, someone practiced guitar, failing beautifully. I set my alarm. I turned off the light. The dark was only dark. I slept.

Morning arrived as a soft insistence. I stood in the kitchen and touched the straight, ordinary line of bone beneath my palm. I cracked an egg into a pan and watched it seize and turn from clear to white. Outside, a delivery truck idled; somewhere, someone told the truth for the first time while someone else decided what to do next. I rinsed my dish, set it in the rack, and dried my hands on a towel striped red, white, and blue because for all its contradictions I am sentimental about this country and its messy promises. I locked the door behind me and took the stairs. On the landing, a neighbor asked how I was—really—and I said, “Better,” and meant it.

At the bus stop, I pulled out my phone. A message from a friend: Movie night? I typed back: Yes. The bus sighed to a halt. I sat in the middle where I could see forward and back and let a woman with a bright, certain voice tell a story in my ears about a girl who remembered the truth and spoke it.

Some days the ache returns like a weather system moving through town. It does not frighten me. It is proof of survival—evidence the body keeps score and also keeps going. If you have been told to be quiet for the sake of peace, hear me: you do not owe your abusers your silence. Standing up for yourself is not cruelty; it is the opposite. It is a kindness to the person you will live with for the rest of your life. There are rooms with fluorescent lights and flags on the wall where someone will stamp a paper and say yes, this counts. There are nurses with steady hands and officers who will take the picture the right way and advocates who will sit beside you when the air gets thin. There are forms and stamps and orders that build a fence you are allowed to stand behind. There are friends with spare rooms and mornings that begin gently and nights that end in quiet you are not afraid of. There is a version of your life that starts at a door you are afraid to open. Turn the handle.

The door will click. The air outside will be cold and honest. You will already be on your way.