The phone buzzed insistently in my pocket, jolting me out of my focus. I wiped the sweat off my brow and stepped outside the makeshift clinic, where the midday sun threw long, white-hot shadows across a dirt courtyard and a ring of cinderblock homes. Somewhere close, a rooster crowed late, confused by the heat shimmering off corrugated tin. My hands still smelled faintly of alcohol pads and eucalyptus soap. I glanced at the screen and felt my stomach drop.

Richard.

I almost let it go to voicemail. Years of dealing with my stepfather’s antics had trained me well—don’t pick up, don’t take the bait, don’t invite the storm. But curiosity and a stubborn, embering hope made me swipe.

“Hello.” I kept my voice neutral.

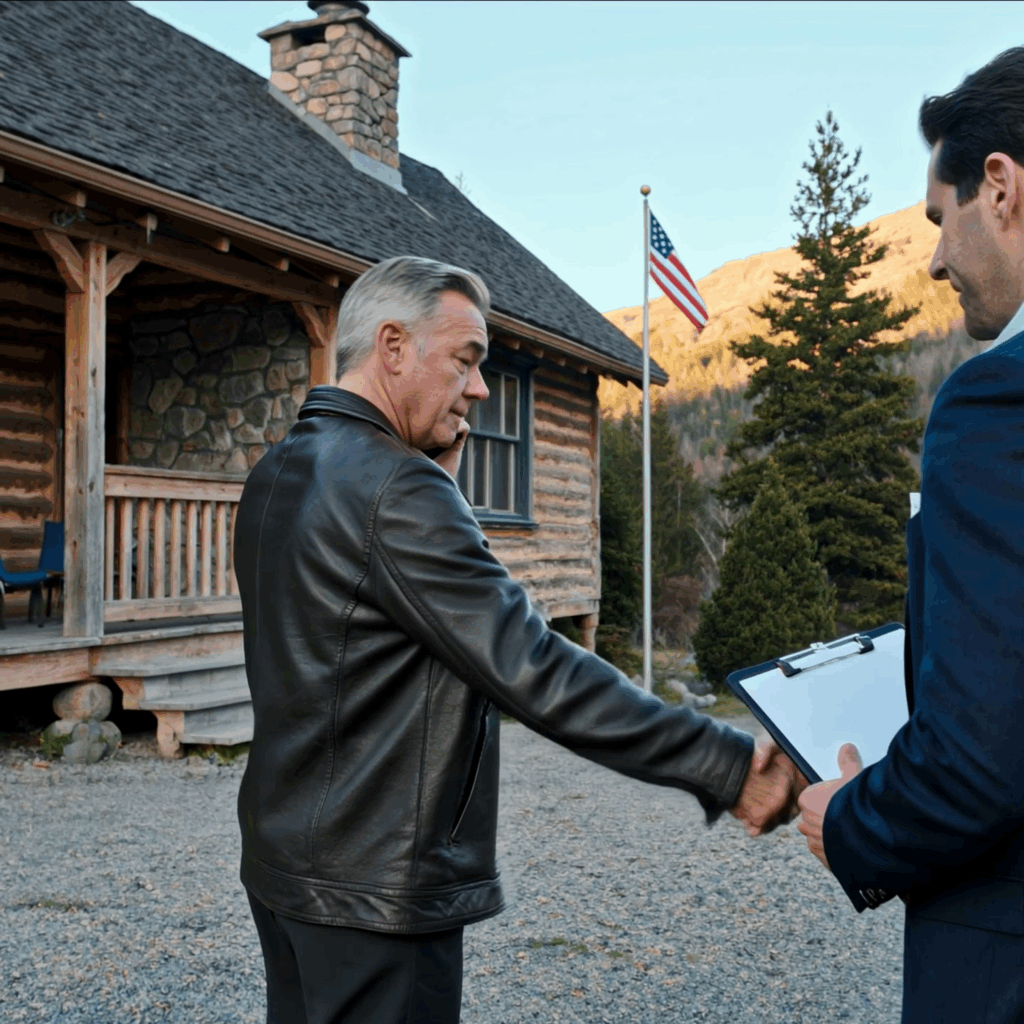

“Catherine!” Too cheerful. His words came with the damp smile I had learned to distrust. “Just thought you’d want to know I sold the mountain cabin.”

I stopped dead in the doorway. Beyond the clinic wall, a child laughed and a dog barked once, as if punctuating a sentence.

“You did what?”

“Sold it,” he repeated, like he was discussing the weather. “Don’t look so shocked. It’s for the greater good. Mine, obviously.” He let out a smug laugh that bloomed hot in my ears.

“My name is Catherine Daniels,” I would write later, in a journal that had seen deserts and snowfields and hotel lobbies with paper-thin drapes. “Richard has been the thorn in my side since I was fifteen.”

Back then, my mother, Janet, had remarried in a small church with white paint flaking from the windowsills and a choir that carried on long after the pastor said amen. Richard had arrived in our lives with easy charm and a toolbox he liked to carry around like a credential. He could fix a leaky faucet. He could fix a wobbly step. He could fix, fix, fix—until something in you believed he could fix people, too. I believed it for a week. Maybe two. Underneath the jokes and the helpful hands was a man whose needs sat at the head of the table.

“You had no right,” I said now, my voice shaking despite myself. “That cabin was not yours to sell.”

“Relax,” he drawled. “I’ve been managing things while you’re off saving the world. What’s the point of holding on to something you aren’t even around to enjoy? It cleared my debts. You’ll thank me later.”

“I’ll thank you when hell freezes over.” I cut the call before I could say something I couldn’t take back.

The courtyard tilted under me and righted itself—anger settling in layers, nausea beneath it, a hard, bright clarity on top. There were twenty people waiting for clean dressings and a mother asking about a cough that had gone on too long. I tucked my phone into my scrub pocket and made it through the afternoon on muscle memory alone. Later, when the last patient had left, I sat on a folding cot under a fan that moved too slowly to matter and stared at the phone as if it were a live coal.

The cabin wasn’t a weekend toy. It was my anchor. A cedar-smelling, knotty-pine, two-bedroom tucked into a fold of the Blue Ridge above Asheville, where the rhododendron tunnels grow thick and the air, even in July, tastes like cold water. My mother and I had spent summers there before she remarried. We ate peaches leaned over the porch rail, juice down our wrists, hiked past old stone walls that vanished into the woods, and fell asleep to whip-poor-will songs. After she died, the cabin was the one constant that didn’t look at me with pity. It was where I went to breathe.

And if Richard thought he could turn my breathing into chips at a card table, he hadn’t met the adult version of me.

I called Laura.

“Hey, Cathy,” she answered, cheerful noise in the background—coffee grinder, voices, the silver rush of an espresso machine. Laura Langley had been my best friend since freshman year at UNC, the kind of friend who texted when the satellite Wi‑Fi cut in and sent me photos of her cat when days were long. Also, my co-owner.

“Richard sold the cabin,” I blurted.

There was a beat of silence. “He what?”

“He says he sold it to clear ‘debts.’ Which means gambling. He thinks he can do whatever he wants. But the co-ownership agreement requires both our signatures for any transfer. He doesn’t have authority.”

Laura exhaled a low whistle that said she was angry and trying not to cuss. “He really thought he could get away with that. That man has no shame.”

“None,” I said. “I need your help. I’ll finish my assignment here and fly back. Can you pull the documents? I want everything ready.”

“You got it,” she said, her voice firm and steady. “I’ll pull the deed, the memorandum we recorded, all of it. We’ve got this.”

After I hung up, a calm settled over me—not peace, not yet, but the calm that comes right before you start building something. Richard thought distance would keep me docile. He forgot I had a spine and a friend who read fine print for fun.

That night, under a sky where the Milky Way looked like someone had spilled salt across black velvet, I opened my journal and wrote until the fan stopped squeaking and the geckos in the rafters fell silent. If rage was gasoline, words were the slowly opening hand that kept me from burning the whole house down. I wrote about the first time Mom took me to the cabin after Dad died. How we slept by the fireplace in sleeping bags because the beds smelled like cedar and dust and a hint of something wild. I wrote about the weekend Laura and I pulled up beige carpet and found nine hundred square feet of old heart pine, straight and honeyed under glue. How we laughed, sticky and blistered, to keep from crying.

In the morning, Laura called. Her voice had shifted into business mode.

“I went through everything,” she said. “We own as tenants in common under C&L Mountain Retreat LLC. The operating agreement requires both managers to sign any deed. We also recorded a memorandum of co-ownership with the Buncombe County Register of Deeds. He can puff all he wants, but he can’t pass title without us.”

Relief shot through me, clean and cold. “Do we know who he ‘sold’ it to?”

“Not yet,” she said. “There’s no transfer recorded as of yesterday. If he tried to do something under the table, the register won’t have it. We’ll need to talk to whoever brokered the deal.”

It sounded exactly like Richard—shortcut king, paper-thin plans. “I finish clinic tomorrow,” I said. “Then I’m home.”

“Text me your landing time,” Laura said. “I’ll pick you up.”

I felt a nudge in my ribs, as if my mother were still here and had found a way to nudge me. Keep your ground, kiddo. You know the trail.

The Asheville airport looked like I remembered it—small, civilized, a certain politeness in the way the mountains seemed to stand at the edges and watch without crowding. Laura was there at the curb in her Subaru, sunglasses pushed into her hair, a grin that cracked open something tight in me.

“You look like you could sleep for a week,” she said, taking my duffel.

“I could sleep for a week in a proper bed with sheets that don’t smell like bleach,” I said. “But first, Richard.”

“First, coffee,” she countered, handing me a paper cup. “Then Richard.”

My phone buzzed before we cleared the airport road. Richard again.

“Well, well, if it isn’t my globe-trotting stepdaughter,” he said when I picked up. His cheer had curdled. “Back to reality?”

“What do you want, Richard?”

“Just checking in,” he said. “Make sure you’re not crying over spilled milk. Cabin’s gone. Deal’s done. No use wasting tears.”

“Funny,” I said, keeping my voice even. “Because as far as the Buncombe County records show, nothing’s gone. Laura and I checked. You can’t sell what doesn’t belong to you.”

A pause. A soft click in his breathing I recognized—gears, recalculating. “Ridiculous,” he snapped. “The buyer paid in cash. Paperwork handled. Done deal.”

“No,” I said. “We own the cabin through an LLC, Richard. Two managers. Two signatures. You have neither. The memorandum is recorded. Any title company worth its stamp won’t close.”

“You think you’re so smart,” he said, nasty now. “Perfect daughter. Always trying to control everything. You don’t know how hard I’ve had it. I did what I had to do.”

“You stole,” I said. “And you gambled with something you never built.”

He hung up.

“Good,” Laura said, eyes still on the road. “Let him hang up on the law, too.”

We drove straight to the register’s office, a brick building with squeaky floors and an old smell of paper and pledge spray. A clerk I recognized from prior permit battles pulled the memorandum from a drawer with a neat, satisfied smile. “Still there,” she said, tapping the seal. “Hard to sell around this.”

We thanked her and walked out into the bright afternoon like girls who had stolen something back and were trying not to look like it.

“Next,” Laura said, “the agent.”

She had already found a name from an email trail Richard wasn’t smart enough to delete—Marina Pierce, a part-time broker who specialized in ‘difficult situations.’ We sat in Laura’s car, dialed, and put the phone on speaker.

“Ms. Pierce,” I said when a crisp voice answered. “This is Catherine Daniels. I believe you were approached about selling our cabin.”

Silence, and then a measured exhale. “Ms. Daniels,” she said. “I didn’t know the full situation. Mr. Cole—”

“Richard Cole,” I supplied. My mother had kept his last name after the divorce because she didn’t want to change the mail again, but I never had.

“Yes,” she said carefully. “He represented himself as authorized. When I asked for a copy of the deed, he sent a blurry photo of something that wasn’t a deed. I flagged it. The buyer hasn’t funded, and I won’t proceed without clear title. If there’s an LLC and a recorded memorandum, that’s more than enough for me to step back.”

“If you have any paperwork he signed,” Laura said, “we’d appreciate copies.”

“I do,” she said. “And Catherine? I’m sorry. You can tell a lot about a man by how he treats paper. This one tried to talk fast.”

After the call, Laura texted a friend at a small firm downtown. By late afternoon, we were sitting in a conference room with glass walls and a view of magnolias on Church Street. Our attorney was a woman in her fifties named Eleanor Price, with kind eyes and the steel you hear more than see.

“This is straightforward,” Eleanor said after skimming the operating agreement. “We’ll send a cease-and-desist to Mr. Cole and Ms. Pierce, and a notice to the identified buyer that any purported sale is void for lack of authority. We’ll also notify the title companies in town. If he gets creative, we’ll seek an injunction.”

“Criminal?” Laura asked.

Eleanor’s mouth made a small, dry line. “Fraudulent misrepresentation is a matter for the police if he continues representing himself as authorized. But let’s build the record.”

“I want to build the record,” I said, feeling the steady rise of something like joy, bright and unexpected. Not because this was fun—it wasn’t—but because for the first time in a long time, I wasn’t letting Richard set the tempo.

Eleanor’s paralegal took copies of texts and the blurred ‘deed’ photo. We walked out into air that smelled like hot asphalt and basil from a restaurant down the block.

“Home?” Laura asked.

“Home,” I said.

My house on Montford Avenue had the look of a place that had been waiting politely: blinds at half-staff, a fern giving up on one side, a small ridge of mail under the slot. I set my bag down with care. The silence folded around me differently than it had in the clinic—this silence knew my name.

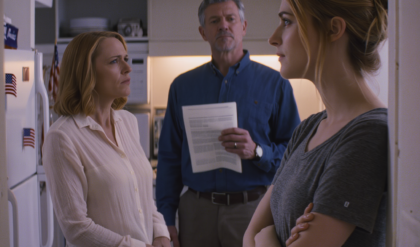

The knock came early the next morning. Three sharp raps, the exact cadence of entitlement.

Richard.

He didn’t wait to be invited. He never did. He stepped past me with the casual arrogance of a man walking into a room he’d paid for, which he hadn’t.

“You look tired,” he said, glancing around, judging, inventorying. He wore a golf shirt that had seen better days and a smile that thought it was charming. “Must be all that traveling.”

“Get to it,” I said.

He put his hands on his hips, an imitation of authority. “You have to understand my position. I was desperate. The people I owed money to weren’t patient. I borrowed the cabin. I was going to make it back. My luck turns—”

“Your luck doesn’t turn,” I said, a little amazed at how even my voice sounded. “It spins you like a dog chasing its tail while you call it destiny. You didn’t borrow anything. You tried to steal it.”

“You’re overreacting,” he said. “It’s a cabin. You’re never there. Why not let someone else make use of it?”

“Because it’s mine,” I snapped, then made myself breathe. “Because Laura values it as much as I do. Because my mother is dead and that place is the last thing that smells like her shampoo and woodsmoke. Because it’s not yours to touch.”

A flicker crossed his face—fear, quickly paved over with anger. “You wouldn’t go to the police,” he said. “You wouldn’t ruin your own stepfather.”

“Try me.”

He muttered something about loyalty, something about gratitude, something about how he had ‘stepped in’ when my mother ‘couldn’t handle things.’ A revisionist history so neat and self-serving it could have been a postcard.

He left in a slam of the door that rattled the framed photos on the entry table—Mom with her laugh thrown back, Laura and me with paint in our hair, the cabin porch with a mug steaming in the foreground and the mountains going blue at the edges like a bruise healing.

I stood there shaking, then laughed. Not nice laughter. Not cruel, either. Something hotter and cleaner. I texted Laura: He came by. He’s rattled.

Good, she wrote back. Paper going out this morning. Coffee?

“Yes,” I told the empty house. “Then court.”

The cabin sat at the end of a gravel road that pinned and unpinned itself through stands of pine and the occasional stray cow. Even the drive up felt like an argument you decided not to have—the road tried to slow you down and you let it. I turned off the engine and sat with my hands on the wheel, listening to the silence that isn’t really silence at all: a creek somewhere below, a woodpecker tapping, the long whisper of wind in needles.

When I opened the door, the smell hit first. Wood warmed by sun, old ash from the stove, a sweetness that might have been leftover apple pie in the walls. I stepped inside and put my palms on the kitchen counter where Laura and I had sanded the varnish down to something you could rest your elbows on.

“Hey, house,” I said. “We’re okay.”

I walked through each room as if I were taking attendance. The woven rug Mom bought from a woman on a roadside stand. The dent in the hallway where I dropped a box of screws. The window seat where, the night after my mother’s funeral, I folded myself in half and only straightened when the birds woke.

Outside, the porch swing creaked. I sat and let the mountains file through their colors—green to shadow to a blue so deep it felt like water. I called Laura and let the ring swallow a minute of quiet.

“How is it?” she asked.

“Like it never left me,” I said. “Like it was worried and then remembered who I am.”

“Good,” she said, and I could hear the smile. “The letter went out. Eleanor CC’d two title companies and the buyer. If Richard so much as breathes near a notary, we’ll know.”

“Thank you,” I said. “For the millionth time.”

“That’s what co-owners are for,” she said. “And friends. Especially friends.”

I stayed that night at the cabin alone. I fed the stove, not because I needed the heat, but because the ritual soothed me. I found Mom’s old kettle and made tea so strong it wanted to fight. I sat at the table and drafted a list: documents we had, documents we needed, a timeline in tidy handwriting that would have made my seventh-grade teacher proud. I made a column for ‘What Richard Will Say’ and another for ‘What the Paper Says.’ I slept with the windows open and woke at dawn because the light insisted.

By mid-morning, an email pinged from the agent. Documentation attached. Buyer on hold. Three PDFs: a standard listing agreement with Richard’s shaky signature, a ‘disclosure’ so badly filled out it made my teeth hurt, and a blurry photo of our memorandum with the recording stamp half cut off. He’d tried to sell a locked door with a blurry photo of the lock.

Laura called an hour later. “Eleanor looped in a detective she trusts—Aaron Miller. He’s with the county. He’ll review and call you.”

Detective Miller called that afternoon. His voice sounded like a man who had seen plenty and still believed in a thing called order.

“Ms. Daniels,” he said. “I’ve reviewed what Ms. Price sent. If Mr. Cole represented himself as authorized to sell property he does not own, and attempted to induce a buyer to purchase it, that’s misrepresentation at best and fraud if money changed hands. We’ll start with the buyer.”

“Thank you,” I said, meaning it. “I don’t—this isn’t about revenge. I just want this to stop.”

“That’s usually what the good ones say,” he replied.

I spent the rest of the day doing the boring, blessed things that remind you the world is not all emergency. I swept the porch. I fixed a squeak at the back step with a drop of oil. I drove into town and bought eggs and a tomato and a pie I didn’t need from a woman who recognized me and said, “You staying long this time?” with the hope of someone who remembers your mother.

“Long enough,” I said.

Two days later, Miller called again. “We’ve spoken with the buyer,” he said. “They agreed to halt the transaction. They were unaware of the co-ownership and say Mr. Cole assured them he had authority. We’re keeping the file open. Ms. Daniels, do you wish to press charges if we determine there’s probable cause for fraudulent misrepresentation?”

I stood at the kitchen window and watched a thunderhead gather over the opposite ridge, tall and precise as a cathedral. I thought about every time I had made myself small to keep peace. About the way my chest felt on the phone with Richard—squeezed, reduced, nineteen again.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

“Understood,” Miller said. “We’ll proceed.”

Richard called that evening. The desperation in his voice had lost its camouflage.

“Do you have any idea what you’ve done?” he snapped. “You’re ruining everything.”

“No,” I said. “I’m protecting what’s mine. You did this.”

“You’ve always been ungrateful,” he said. “I stepped in when your mother couldn’t handle things. I kept the lights on.”

I laughed, a sharp, wild sound that surprised me. “Mom kept the lights on. I kept the lights on after she died. You kept the game on and asked us to clap.”

“This conversation is over,” he said.

“For once,” I said, and hung up.

The arraignment was on a Tuesday in a courtroom so ordinary it broke my heart a little—water-stained ceiling tiles, a clock running two minutes fast, a flag that needed dusting. Richard stood at the defense table in a suit he’d worn to Easter brunches. He looked smaller than I remembered and more dangerous, the way a cornered animal is dangerous. He did not turn to look at me, though I watched his shoulders tense when Eleanor leaned in to speak to the assistant district attorney.

When the clerk read “fraudulent misrepresentation” and “attempted theft of property,” his jaw tightened. He pled not guilty. The judge, a woman with a voice like a metronome, set conditions and dates. When she asked if there were victims present who wished to be heard, my name detached itself from my ribs and walked to the podium.

“I’m not here because I enjoy this,” I said, surprised at how steady I sounded. “I’m here because my stepfather has crossed lines for years and learns only what the paper teaches. My friend and I built that cabin. It is not a poker chip. I don’t want him in prison. I want him to stop.”

The judge nodded once, a precise acknowledgment, and set the next hearing.

Outside, Eleanor walked with me to the curb. “You did well,” she said. “Clear. Not vindictive. Juries like that. Judges do, too.”

“I’m not angling for a jury,” I said. “I’m angling for my life back.”

“Those aims are not mutually exclusive,” she said, the corner of her mouth lifting.

Laura pulled up, and I slid into the passenger seat. She squeezed my hand hard enough to hurt. It was the good kind of hurt—the kind that tells you you’re not made of glass.

“Pizza?” she said.

“Pizza,” I agreed.

In the weeks that followed, life began to thread itself back into something like normal, or whatever counts as normal when you’ve filed a criminal complaint against family. I worked remote shifts for the nonprofit from my kitchen table. I ran the trail above the river at dawn and let my lungs remind me they were bigger than my fear. On Saturdays, Laura and I drove up to the cabin with a borrowed nail gun and a playlist that swung from Springsteen to Dolly without apology.

We rebuilt the sagging porch rail. We re-caulked the windows. We planted wildflowers along the edge of the drive—black-eyed Susans and blue phlox—so that, come spring, they’d surprise us again. We argued over paint colors as if they were moral questions. We solved the world for fifteen minutes at a time, then laughed at ourselves and solved it again.

Sometimes at dusk, a fox would appear at the edge of the clearing, look at us with clinical disdain, and vanish. Once, a black bear nosed the compost bin, and I banged a skillet with a wooden spoon, laughing and crying at the same time because everything, suddenly, felt so alive.

My mother called exactly once. The call came in from a number I didn’t recognize, and when I answered, her voice arrived tentatively, like a hand that wasn’t sure it would be taken.

“You know how he gets,” she began, her old defense worn thin.

“I do,” I said evenly. “And that’s why I did what I had to do.”

She was silent a long time. I could hear the TV in the background—some game show where everything is too loud and everyone is too enthusiastic.

“I hope you find peace,” she said finally.

“I already have,” I said, and we left it there—two women on a line that used to strangle us, now just a thread we could lay down.

Detective Miller kept me apprised without drama. “We have enough,” he said one afternoon. “The DA’s moving forward.” Another day: “His attorney is open to a plea if restitution is included and he admits the misrepresentation.” Eleanor translated that into plain. “He’ll have to say out loud what he did,” she said. “Sometimes that’s the only thing that gets through.”

When the day came, the courtroom felt smaller. Richard stood, eyes on the table, and answered yes to the questions the judge asked. Yes, he told the buyer he had authority he did not have. Yes, he accepted funds. Yes, he understood. Yes, he would make restitution to the buyer for costs and to me for the fees I incurred trying to clean up his mess. Yes, he would attend a gambling treatment program as a condition of his suspended sentence. No, he would not contact me.

He did not look at me as he left. I did not need him to.

On the drive back to the cabin, Laura turned the radio down and said, “What now?”

“Now,” I said, and the word felt like opening a window, “we live.”

We stopped at the hardware store for new house numbers because the old ones had rusted and leaned. We bought a brass 7, a brass 3, and a brass 9 that gleamed like possibility in my palm. We bought a weatherproof box for the spare key and didn’t tell anyone where we put it. We bought a bell for the porch, not because we needed a bell, but because it felt like the kind of thing that belongs to a place that has survived an attempted theft of its soul.

That night, the mountains drank the sun in three swallows. We sat on the steps, legs touching at the knee, and passed a bottle of cheap champagne we had no business enjoying as much as we did. Laura raised it in a half-toast.

“To us,” she said.

“To not letting anyone push us around,” I said.

“To paper,” she added, grinning.

“To paper,” I agreed, laughing. “And to the kind of love that reads it.”

We didn’t talk about Richard anymore after that. Not out of denial—out of decision. I had spent years letting him occupy expensive real estate in my head. No more free rent. If he got better, I hoped it took. If he didn’t, I knew we had built guardrails strong enough to keep him from crashing the gates again.

When the leaves turned, the cabin put on its show without apology. The maples went red first, like a dare. The oaks followed, all gold and copper. The sourwoods flamed up the holler like a rumor. I raked until blisters formed and healed and hardened, then stopped raking and let October do what it was built to do.

On the first cold night, I lit a fire in the stove and sat on the floor with a mug of tea and my journal. I wrote about a woman who had been certain she was small and found out she was not. I wrote about how the law is dull until it’s the only music that drowns out lies. I wrote about Laura’s hand on my knee in the courtroom and a fox watching me like it knew more than I did.

I wrote this, last: The cabin is not just four walls. It is the part of me that refused to be sold.

Weeks became a season. I signed up for another field rotation for spring, this time stateside, a mobile clinic serving farmworker communities. I’d go for three weeks and come back to the cabin that would be here because I had fought for it, because Laura had fought for it, because the paper had stood and the mountains had agreed.

One morning, I took Mom’s kettle down from its hook and cleaned it until it shone. I brewed coffee and carried it to the porch in a mug Laura had bought me that said Stay Wild in a font too pretty for the sentiment. I sat and watched a hawk ride thermals I couldn’t see.

My phone buzzed, and for once, the name on the screen didn’t make me brace. It was an email from a teenager I had met at the clinic, thanking me for promising that bodies can heal and so can families, sometimes. I answered with a picture of the mountains and a sentence I had earned: “You get to draw your boundaries and build on the inside of them.”

On the edge of the porch, beside the bell we’d mounted, a small metal plate caught the sun. Laura had it engraved and installed without telling me, like a magic trick. I bent to read it.

THIS PLACE IS NOT FOR SALE.

I laughed, that good laugh again, the one that feels like oxygen. A chipmunk scolded me from under the steps, offended at my joy. I told him he’d get used to it.

When night came, the stars arranged themselves the way they always have when you remember to look. I thought of the girl who had answered the phone outside a clinic, and the woman who now let the phone sit because the mountains were speaking. They said: stay as long as you like. They said: you did not owe anyone your home. They said: welcome back.

I believed them.

And when the wind moved through the pines, it sounded like a thousand pages turning, all at once, to the part where the heroine stops asking permission and starts living the life she chose.

So I did.