My Parents Called Me In A Hurry Saying: ‘Please We Need You Here This Instance – It’s Urgent!’……

I was halfway through a twelve‑hour shift when my phone vibrated against the scrub pocket over my heart—one, two, three times in quick succession. I didn’t have to look to know it was family. The pattern was familiar: my mother first, my father next, my sister last. Emergencies, in my family, arrived as a chorus.

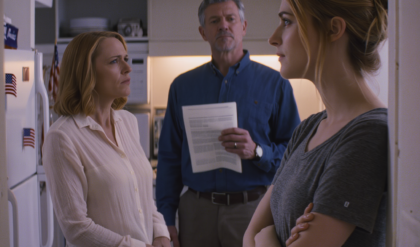

“Please, we need you here this instance. It’s urgent.” My mother’s voice, breathy and elevated, came through the speaker. She didn’t wait for me to answer; she never did. “Come now, Sarah.”

I asked for a float nurse, handed off a med pass, and told charge I had a family emergency. Nobody questioned it. People in hospitals understand that emergencies are not always the ones arriving by ambulance.

County General’s automatic doors sighed me out into the late afternoon. The air smelled like rain and cut grass. I drove the familiar streets on autopilot, telling myself it could be anything—Dad’s blood pressure spiking, Mom fainting, my sister Madison getting into one of her melodramas with a boyfriend I’d never met. I told myself not to catastrophize, but the part of me that was a mother cataloged worst‑case scenarios anyway. Emma’s white cane leaned in the passenger footwell like a little question mark.

When I pulled into my parents’ driveway, the yard was immaculate, each blade of grass disciplined. The inside of the house was as I remembered it: curated calm, creams and soft grays, a decorative throw blanket draped at a perfect forty‑five‑degree angle, the TV murmuring a daytime talk show with the sound low. My parents were fine. They were better than fine. They were laughing.

Madison was there too, pouring wine into stemless glasses like she owned the place. She was sun‑kissed in a way you only get if your biggest decision is which gym mirror has the best lighting. She looked up, gave me a smile I’d seen a thousand times—a smile that meant Now watch me.

“What happened?” I asked, still in scrubs, badge face‑down in my pocket, hospital scent clinging to my skin. “You said urgent.”

Mom patted the sofa cushion beside her. “Tell us, honey, how much money you need so we can all go on a holiday.”

For a heartbeat I didn’t understand the words. They slid over the surface of me, refused to stick. “I just came from the hospital,” I said. “What exactly is going on?”

Mom laughed, the practiced trill that had charmed neighbors and PTA committees and church brunches for years. “Who said ‘we’? Only us. Just hand over the emergency savings to your sister.”

“No,” I said immediately. “That fund is for Emma.”

My father adjusted his reading glasses, the better to look disappointed. “Stop whining, Sarah. A trip is more important than a useless kid’s eyes.”

I had heard many ugly things in my life, but never with that clarity. “Don’t talk about my daughter like that.”

“She’ll never see anyway,” Dad said, and because he had known me since I was born, he spoke as if he were reading a lab value and not pronouncing a sentence.

Madison sipped. “She won’t hand it over this way.” Her voice was a singsong. Then she stood, crossed the room in a handful of quick, bright steps, and drove a nail through my left foot.

It happened at once and forever. The nail punched through the top of my sneaker, then skin, tendon, bone, hardwood. The world went white at the edges. I didn’t scream. Years in the ER teach you what pain is and what it is not. Pain is data. Pain is a bright flare of information you can file and work around.

Blood welled up around the metal shaft and began to fan across the pale plank floor. My mother tilted her head like she was checking the lighting in a dressing room. My father leaned forward, interested in a way he had not been in me for years. Madison took a step back to admire her work.

I understood, with the clean certainty of a scalpel, that this was not shock. This was clarity.

“Madison,” Mom said, as if we were planning brunch, “grab the checkbook from her purse. She keeps it in that ugly brown bag.”

Madison moved toward the entry table where I’d dropped my purse on my way in. She bounced on her toes, blonde hair glossy. She had been the favorite since the day she arrived—my parents’ golden retriever who could do no wrong. When she crashed Dad’s sedan at seventeen, the other driver was reckless. When she stole from a college roommate, it was a misunderstanding. When she slept with my ex‑husband and blew a hole through my first marriage, they told me I should have been more attentive to his needs.

“The checkbook won’t help you,” I said, keeping my voice level because that was the only thing I could control. “The emergency fund isn’t in checking.”

Dad’s face darkened like a storm forming over a lake. “Where is it then? That money was for family emergencies, and your sister’s mental health requires a vacation to Cancun. The doctor said so.”

“Which doctor?” I asked. “The one who prescribed her anxiety meds she sells at her gym?”

Madison whirled around, color rising high on her cheeks. “You can’t prove that.”

“I’m a registered nurse,” I said evenly. “I know what street value looks like. And I know your clients aren’t carrying prescriptions for the Xanax you’re dealing.”

Mom set down her glass a little too hard. “How dare you accuse your sister. She’s going through a difficult time. That’s why we need the money. All thirty‑seven thousand dollars. You’ve been hoarding that fund for years. Time to contribute to this family.”

She knew the number. Somehow she knew—I didn’t have to ask how. People like my parents always know the numbers that matter to them.

I had built the fund slowly and stubbornly since Emma’s diagnosis—Leber congenital amaurosis—when she was two. Every extra shift, every holiday bonus, every tax refund went where it needed to: toward a chance. Not a miracle, not a guarantee. A chance. The team in Boston offered hope that mattered—no snake oil, no wishful thinking—real science with a slim window before the brain’s pathways stopped listening for sight.

“That money is for Emma’s treatment,” I said. I could feel my pulse in my mouth. “She has an appointment with Dr. Richardson in three weeks. The procedure could restore partial vision.”

“Partial,” Dad echoed, like the word itself were an insult. “So she’ll still be mostly blind. What’s the point? You’re throwing money at a lost cause when your sister actually needs help.”

The nail shifted when I adjusted my weight, and pain flared hot. Blood ticked off the edge of my shoe and puddled on their perfect floor. Good, I thought. Let it stain. Let this house learn what it feels like to keep a mark.

“Lost cause,” I repeated, tasting it like metal. “You’re calling my child a lost cause.”

“She is,” Madison said brightly. “Everyone knows it. You’re just too stubborn to admit it. That kid will never have a normal life, never drive, never see her own wedding day—if she even finds someone desperate enough to marry her. But me? I have potential.” She smiled for herself. “I could still turn things around with the right opportunities.”

Madison had never held a job longer than eight months. She had dropped out of college three times, been fired from a jewelry store for theft, and presently called herself a wellness influencer to her forty‑three Instagram followers, most of which were bots she bought in a midnight burst of optimism. But yes, potential.

“The nail,” I said. “Pull it out.”

“Not until you transfer the money,” she replied, examining a thumbnail. “Or better, give me the login. I’ll handle it.”

“That account requires two‑factor and my fingerprint,” I lied smoothly. “You’ll need me conscious and cooperative.”

Mom brightened. “See? We can work together. Authorize the transfer and we’ll drive you to the ER.”

Something hardened and settled inside me then—a decision that had been assembling itself for years. I let it click into place.

“I need my phone,” I said. “It’s in my purse.”

Madison dumped my bag out like a raccoon—keys, wallet, Emma’s medical cards, everything scattered—then handed me only the phone. If she thought removing potential weapons made me harmless, she hadn’t been paying attention these past few decades.

I unlocked the screen, aware of three pairs of eyes. My foot was fire. I needed a tetanus booster, antibiotics, maybe surgery. But first I needed a record.

I opened my banking app, let my hand tremble just enough to look convincing. I navigated to the emergency fund—the one that read $37,283.19—then tilted my phone on my thigh so the camera caught the whole room. The newer wide‑angle lens did the rest. Then I opened Messages.

“Mom, Dad, Madison,” I said clearly, lifting my head so the audio would be crisp. “Just to confirm before I make this transfer, you want me to give you my daughter Emma’s medical fund—the money set aside for her vision treatment—so Madison can go on a vacation to Cancun?”

“Yes,” Mom said, annoyed. “We’ve covered this. Stop being dramatic.”

“And you’re refusing to let me leave or seek medical care for my foot until I comply?”

“Finally,” Madison said, eye roll and all. “She gets it.”

“And Dad, you said Emma will never see and called her a useless kid.”

He scoffed. “I said she’s not worth throwing money at. There’s a difference.”

“Just making sure,” I said, fingers moving fast now.

I wasn’t transferring anything. I was texting Rachel, my best friend from the hospital, and Derek, my ex‑husband, Emma’s father.

To Rachel: Emergency. Parents’ house. Call 911. They’ve assaulted me and won’t let me leave. Need police and ambulance. Keep Emma safe.

To Derek: At my parents’ house. They want Emma’s fund. I’m recording. Call your lawyer brother now.

Send. Then I opened the bank app for real.

“Okay,” I said, letting them see a balance, making sure the camera saw their faces. “Here’s the account. But you need to understand something. The bulk of this money is in a medical savings trust. If I pull for non‑medical reasons, that’s fraud. There are penalties.”

It was half‑true. Most of it was in that trust, the rest in a high‑yield savings account. The truth, as ever, was useful.

Madison moved into my space, breathing wine. “You’re lying. Transfer now or I get another nail.”

“Another nail?” I said, letting my voice carry. “You’re threatening to drive another nail into my body if I don’t commit financial fraud and deny my blind daughter medical treatment?”

Dad gestured with his hand as if to bat the air into compliance. “Stop making it sound terrible. We’re family. Family helps.”

“Family,” I said softly, and felt whatever was left of the word dissolve.

Sirens /begin as a rumor. You think you’ve imagined them. Then they grow until the neighborhood knows. Madison heard them at the same moment I did. Her head snapped to the window.

“Did you call the cops?” she shrieked, lunging for my phone.

Despite the nail, I twisted, threw the phone under the entertainment center. It skittered out of reach and locked itself.

“You crazy—” she started.

The pounding on the door interrupted. “Police! Open the door!”

Dad stood like a man caught in the wrong hat, looked to Mom, looked to Madison. I watched the calculus flicker over their faces, the coordination they had perfected over a lifetime of excusing my sister.

“It was an accident,” Mom said quickly, smoothing her blouse. “She stepped on a nail. We were having a family discussion about money.”

“A civil conversation,” Dad added. “She got upset, paced, hurt herself. We were about to drive her to the hospital.”

Madison chimed in, bright as a pageant queen. “We called her to help with Emma’s bills as a surprise.”

The door swung open. Three officers. Behind them, two paramedics with a stretcher. The lead cop, a tall woman with a gaze like a ruler—straight and unforgiving—took in the room in a breath.

“Ma’am, are you Sarah Chen?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Registered nurse at County General.” I lifted my foot. “I’ve been assaulted and held against my will.”

“That’s not true!” Madison shrieked. “She’s lying.”

The officer raised a hand. “Everyone stay where you are. Ma’am”—to me—“we received a 911 call reporting an assault and false imprisonment. Tell me what happened.”

I told her. Clear, clinical, complete. While I spoke, one officer located my phone where it had landed.

“The passcode is 081516,” I said. “Emma’s birthday—August 15, 2016.”

The paramedics crouched to examine my foot. One of them—Kelly, who I knew from inter‑hospital drills—met my eyes and shook her head like she could unwind time if she glared hard enough.

“You’ll need surgery,” she said under her breath. “Tendon involvement. Possible bone nick.”

The officer watching my recording didn’t hide her reaction. I saw her jaw tighten at Madison’s voice, at the clear, almost bored timbre of my parents’ agreement. She looked up like she wanted someone to explain the world to her differently.

“This shows assault with a deadly weapon and attempted extortion,” she said finally. “We’re taking your family into custody.”

My mother folded like paper, then sprang up angry. “You can’t arrest us. She’s our daughter. This is a family matter.”

“Assault is not a family matter,” the officer said. “Turn around.”

Chaos is loud and also quiet. Madison made it to the front door before an officer caught her. Dad talked rights and lawyers and lawsuits. Mom clutched her chest; the paramedics read her drama as rhythm and found nothing wrong.

Kelly and her partner worked my foot free of the floor. The nail came out with a sickening, cartoonish sound. Blood followed, dark and fast. They wrapped, elevated, started an IV. The room became practical. Forms, vitals, transport.

As they loaded me, Madison twisted to spit a final line. “You’ll regret this. We’re family. You can’t do this to family.”

“You did it to yourselves,” I said. “And to my daughter, when you called her useless.”

They were ushered into cruisers: Madison still performing for a camera no longer there, my mother demanding a manager like the world was a store, my father small in a way I had not seen since I was a child.

The lead officer came back. “We’ll need your full statement at the hospital,” she said. “But I want you to know—the video is damning. Your sister’s looking at assault with a deadly weapon, false imprisonment, and attempted extortion. Your parents are accessories. This is serious time.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it.

The ambulance hummed. The ceiling lights of the rig marched by like small moons. Pain medication melted the edges of the world. Questions came; I answered. In triage, familiar faces waited: Rachel with her brows knit together, the charge nurse with a softness I had never seen in her eyes.

“They called the hospital for you an hour ago,” Rachel said, squeezing my hand as the surgeon examined my foot. “Said Emma was hurt. We told them you’d left for a family emergency. I’m sorry, Sarah. I should have guessed.”

“This isn’t on you,” I said. “They would have found a way.”

Derek arrived with Emma just as I was being wheeled to OR. Emma’s hand sought mine, small, sure. Her face tilted toward my voice—an angle every parent of a blind child knows.

“Mommy,” she said. “Miss Rachel says you got hurt.”

“Just a little accident,” I said lightly. “Doctors are going to fix it.”

“Are we still going to Boston?” she asked. The question was the size of her world.

“Absolutely,” I said. “Nothing is stopping us.”

Surgery took three hours. The nail had severed a tendon and fractured two small bones. The surgeon was good. I would walk. Maybe with a limp in bad weather. I filed that away under Acceptable Loss.

In the days that followed, the case built itself. There are stories so clean they assemble like an instruction manual. The video played at the bail hearing and then slipped onto the internet like everything does. The clip—my voice steady, my family’s voices clearer than they had any right to be—ping‑ponged from phone to phone, city to city. The caption wrote itself: Family Drives Nail Through Daughter’s Foot Demanding Money Meant for Blind Grandchild.

Public opinion didn’t waver. Neighbors were interviewed. Former coworkers. People Madison had wronged who shrugged and said, yes, that tracks. A pattern of enablement presented itself like a bad wallpaper you suddenly realize is everywhere once someone points it out.

The police dug where the recording pointed. Madison’s side business with prescription meds unraveled fast. The physician who supplied her was charged. The theft warrant she’d dodged bloomed under light. My parents’ finances told a story too: no contributions to Emma’s care despite comfortable retirement accounts; transfers bailing Madison out that were labeled in bank memos as “gifts,” “help,” “she needs us.”

Marcus, Derek’s brother, took the case pro bono because he had a soft spot for justice and for Emma. He prepared me like he would a nurse prepping a patient for a hard procedure. “They’ll try to make you look vindictive,” he said, sliding a legal pad across his desk one afternoon. “They’ll say you set them up.”

“I left my shift because my mother said there was an emergency,” I said. “That wasn’t a setup. That was parenting.”

“They’ll say you went there to record them.”

“I went there because I always go,” I said, and Adam’s apple or not, he knew I was right.

We practiced for hours. Rachel played defense attorney, mean in the way only a friend can be for rehearsal. Derek watched for tells—when my jaw clenched, when my shoulders rose. Emma’s therapist, Dr. Feldman, helped me lay down the weight so I could walk into court without carrying everything at once.

“You will see them,” she said. “Your parents. Your sister. Talk to the part of you that wants to look away. Tell her you’ve got this.”

I did. Over and over until the part of me that was twelve and waiting for someone to notice I was good enough finally sat down.

The defense tried to keep the recording out. Claimed duress. Claimed privacy. The judge—silver hair, steady hands, eyes that had seen everything twice—denied the motion in less time than it takes to draw blood. “She recorded in a common area on her own device,” the judge said. “Admissible.”

Madison’s attorney, a slick young man with a tie the color of gasoline, suggested I was unstable. He subpoenaed my medical records, hunting for a diagnosis he could throw like confetti. He found nothing because there was nothing to find; a handful of therapy sessions post‑divorce does not make a person dangerous.

My parents’ lawyer tried community reputation. Church attendance, taxes paid, volunteer hours logged. She said one bad afternoon shouldn’t define a life. The prosecutor, Daniel Ooa, was prepared. He queued emails in which my mother referred to Emma as “Sarah’s problem.” He played a voicemail where my father told me throwing money at blindness was throwing good money after bad. One bad afternoon, the evidence showed, was just the loudest chapter in a long, quiet book.

I took the stand. I told the story as cleanly as I could. I kept my voice from breaking not because I needed to be strong but because I wanted the jury to hear me. When the prosecutor asked, I removed my shoe and sock and showed them the scar, a puckered comma that still ached when it rained. A court reporter looked up at that—just enough to mark the moment.

The jury did not take long. They filed back in with faces that had made decisions. Guilty on all counts. Madison got eighteen years. My parents six each. The judge, a grandmother, used the word “reprehensible” and meant it.

Nothing about the verdict felt like triumph. It felt like a breath I had been holding since childhood finally leaving my body.

Life rearranged around that new emptiness where my birth family had been. I learned to walk again without favoring the foot. Physical therapy carved back strength. James, my PT, told me I was stubborn in the way that keeps people out of wheelchairs. I took it as the compliment he meant.

At work, I fell back into rhythm—charting, rounding, educating, advocating. Nurses know how to keep the river moving even when the banks have shifted. The break room cake they surprised me with when I returned to full duty said Welcome back, Sarah. The frosting looped awkwardly, letters skidding into each other like children on a slip‑n‑slide. It was perfect.

People asked for interviews. I declined. The story had enough voices. I didn’t need mine amplified beyond the sworn testimony I had given.

Donations trickled into the fund from strangers who watched that video and wanted to lift something heavy with me. Five dollars here, twenty there. It added up. By the time we flew to Boston, we had over ninety thousand dollars—enough for the procedure, post‑op care, and a cushion to let me sleep when worry crept around the edges.

Dr. Richardson performed the procedure on a bright Tuesday in October, exactly seven months after the nail. The surgical suite smelled like sterile resolve. I held Emma’s hand until anesthesia folded her small body into stillness. Derek stood on the other side and traced circles on my shoulder the way he used to when the world felt too loud.

When they peeled away the bandages days later, Emma’s first words were about color. “It’s like…like lights,” she breathed. She could see shapes, shadows, the blurred oval of my face. She would never be twenty‑twenty, but she could see me enough to place her hand where my cheek met my smile.

I cried in a way I had not allowed myself in months. Derek cried. Dr. Richardson pretended he had something in his eye and then gave up pretending.

My birth family saw none of it. Prison schedules do not include pediatric miracle rounds. I returned their letters unopened. I declined visits. I kept the restraining order template ready, a blank form that promised a future where our boundaries remained intact.

The weeks before the trial ended, my aunt Carol reached out. She had been estranged from my mother for years. We met for coffee near the hospital. She told me stories that rearranged the furniture in my memory: my mother engaged to a wealthier man once, self‑sabotaging until he left; getting fired for theft and then rewriting the narrative until she was a victim again. She said my mother had always preferred Madison because Madison reflected the parts of herself she refused to examine. “You reminded her of our mother,” Carol said softly. “Steady, responsible. She resented you for it.”

Hearing it didn’t fix anything. It wasn’t meant to. It allowed me to stop asking the question children ask in the quiet: What did I do wrong? The answer, it turned out, was nothing. There was no perfect self I could have contorted into that would have earned uncomplicated love in that house.

Emma thrived. With partial vision, she navigated more independently. She learned to read large print alongside braille. She drew pictures that were mostly shapes and color fields, and then one day she drew a lopsided heart and said, “It’s you.”

Derek remarried a kind woman named Jennifer who never tried to replace me and never treated Emma as anything less than a gift. We built a working family out of the materials we had: dinners together, shared calendars, holidays negotiated with grace.

The scar on my foot weathered into something pale and stubborn. It ached when it rained, then when storms threatened, then only when I stood too long on cold floors. I learned its language. It learned mine. It became, eventually, not a reminder of pain but of a line I had drawn and refused to cross again.

People sometimes wondered aloud if I regretted pressing charges. If I should have sought therapy as a family, attempted a repair, made room for an apology. I don’t argue with people’s hypotheticals. I only know the look in my sister’s eyes as she raised the hammer and how my parents laughed while blood spread across their perfect floor. I know what my daughter’s face looked like when she could finally look back at me. Between those two images, all the moral math I will ever need resolves itself cleanly.

Emma’s next procedure is on the calendar for next year. Dr. Richardson believes there’s more to gain. We’ll go back to Boston, stay in the same hotel, walk the same river path. She’ll see the fall leaves better this time, the Charles River, the busy streets in sharp enough relief to memorize them. My foot will probably ache. We’ll pack warm socks. We’ll keep moving.

The emergency fund still exists. It grows carefully with each paycheck. It is earmarked for Emma’s future—education, care, independence. It is, finally, protected not by my ability to keep everyone happy but by law and by the knowledge that I have already survived the worst my family could do.

I sleep. Not like the dead—like the living. My conscience is quiet. The house is quiet. When I wake at night, it’s often to Emma’s whisper from her room down the hall: “Mom? Are you there?”

“I’m here,” I say into the dark, into the light she can now almost see. “I’m right here.”

If there is an “after” to any story like this, it is not glittered. It is ordinary, which is the best kind of prize. It’s school lunches and ophthalmology follow‑ups, a car that needs new tires, a calendar shared with an ex‑husband and his wife who has become, miraculously, a friend.

Rachel texts me grocery memes and proofreads my victim impact statement. Marcus sends me articles about case law in which victims are allowed to keep viral recordings offline after a trial. We don’t try to make meaning out of what happened because that implies someone had a lesson for us tucked inside their cruelty. We make use of it instead: better policies at the hospital for verifying so‑called emergencies; a small fund other nurses can tap when they need to flee family situations that look like mine did.

Sometimes the scar throbs out of the blue, and I am back in that room with the pale floors and the careful decor that meant nothing when blood asked to be noticed. When that happens, I breathe like I teach my patients to breathe—counting in fours, finding a spot on the wall, letting the wave crest and pass. Then I look at Emma reading on the couch with her magnifier, tongue caught between her teeth in concentration, and I am returned to the present so quickly it feels like a blessing.

There is a restraining order paperwork template saved in three places. My phone backs up to the cloud every night. The recording is archived. Not because I live in fear—I don’t—but because prudence is a bridge you build before the river rises. If my family is ever released and decides to remember I exist, the past will be ready to meet them in a court of law.

And yet, most days, I forget them. Not as an act of magnanimity. As an act of conservation. There is only so much room for the people who love you and the people who tried to break you. I choose the former now because I know the cost of the latter.

What did I learn? The question lands like a cliché until you sit with it long enough for it to become true. I learned that love is not a contract signed at birth. I learned that family is not owed your loyalty when it asks you to burn your child at the altar of someone else’s comfort. I learned that the body can be wounded and still carry you on the exact day your child needs you steady. I learned that justice isn’t revenge; it is dignity with a gavel. And I learned that the word “urgent,” in the wrong mouth, is just a key someone uses to let themselves into your life.

In my house, “urgent” means Emma’s laughter when she realizes she can track the path of a kite against a blue October sky. It means pizza night after a long week of double shifts. It means a phone call from Rachel that begins, “You free? Because I’m parked outside and I have coffee.”

The future is not spotless. No future is. But it is ours. And there are mornings when Emma pads into my room and climbs into bed and traces the outline of my scar with a small, reverent finger as if it were a map we used once to find our way out. In a way, it was.

On a calendar in the kitchen, in a square two months from now, there is a note in marker: PT eval—Mom. Not because I am broken. Because I have decided to keep choosing strength with the same stubbornness I used to survive. There is another note the week after: Emma: class field trip. We’ll pack snacks. We’ll label everything. We’ll tell the teacher she prefers the front of the bus to the back. We will keep living.

When the rain comes and my foot twinges, I put on warm socks and remember. When the sun comes and Emma squints and then lifts her chin to meet it, I remember too. Not the pain. The line. And that I stepped over it, carrying her, into this life that is ours now, urgent only in the best ways.

I didn’t sleep the night after sentencing. The house held its breath like a patient waiting for the first post‑op sign that everything was going to hold. The dishwasher hummed. The furnace coughed. I made tea and didn’t drink it. At 3:17 a.m., I sat cross‑legged on the kitchen floor and traced the raised ridge of my scar through a sock and told myself—out loud because sometimes you need to hear it—that the worst thing had already happened and still, here we were.

In the months between the nail and the gavel, my life divided into stations like the monitors at work: vitals stable, airway patent, pain controlled, family notified. Except my family had become a word I handled with tongs, and the pain was a kind that didn’t respond to a numeric scale. I could work with that. Nurses live by triage. You look at what’s in front of you, you intervene, you reassess.

I wasn’t the first patient I’d followed down a hallway to surgery, watching the ceiling tiles go by like a flip book. I wasn’t the first person to wait in a plastic chair while a surgeon summarized his own handiwork in gentle euphemisms that softened nothing. But I was the first mother I’d met who had to schedule her tendon rehab around school pickups, ophthalmology appointments, and the rhythm of a child’s new world as it flickered into visibility. If there is a religion for the ordinary miracle, it’s built out of to‑do lists and faith that keeps choosing.

The Before Inside the After

In the quiet after the verdict, the memory of the morning of the call kept replaying—not because I wanted to live there but because the tape ran on its own.

Behind the nurses’ station that day, I had been recalculating potassium replacement for a cardiac patient when my phone jittered against my chest in that particular pattern—Mom, Dad, Madison. Emergencies, in my family, were a choreography. I asked for a float. I handed off meds like passing a baton in a race I’d run a thousand times. “Family emergency,” I told charge, and anyone who’s ever worked a hospital nodded with a kind of mercy that doesn’t require details.

A nurse knows what she will do when the fire alarm goes off and smoke lifts under the door. You move patients, you grab charts, you roll the code carts out of harm’s way. What I did not know, what I could not have known, was what I’d do when the fire was family and the smoke smelled like Chardonnay.

I remember driving past the park I used to take Emma to, back when she mapped the world with her hands, palm first, and I named every leaf for her. I remember the stoplight that refused to turn and the temptation to believe that the universe was installing red lights as a warning. The truth is always less cinematic. It was a Tuesday. People had places to be. So did I.

The driveway was as precise as a haircut. The hydrangeas were fat and smug. I walked in without knocking because I still thought knocking was for other people. That’s its own kind of faith, I guess—believing the door will always open for you. It did. Once.

You know the rest of that scene already—the nail, the white flare, the way my mother tilted her head like this was a lighting problem she might fix by moving a lamp, my father angling his reading glasses as if better focus would change anything. You know the words they used about my daughter, and you know the sound a nail makes when a paramedic backs it out of a foot and the floor gives up its grip with a small resigned pop. What you don’t know is how quickly the world can narrow to a lens and how quickly a person you used to love can become B‑roll.

The Room Where Stories Break

Later, I would learn that the lead officer had a daughter of her own and had once sat in an elementary school parking lot, clutching a steering wheel through a parent‑teacher conference where the words “delayed” and “accommodations” made her feel like she had swallowed a magnet that only collected the worst. Later, I would learn that Kelly, the paramedic, had filled out my chart with the small ferocity of someone who refuses to let a fellow provider’s pain be treated like a footnote.

But in that room, the only stories that mattered were the ones that could be proven. Here is what we could prove: the time stamp on my mother’s call, the pattern of missed calls that followed, the text to Rachel, the text to Derek, the recording—a clean slice of truth any jury could hold without it bleeding through.

“What are you doing?” Madison had demanded, watching my fingers move across glass.

“Authenticating,” I’d said. “Bank security is intense.”

People like to say that in a crisis, you don’t rise to the occasion; you fall to the level of your training. I fell to the habits nursing had drilled into my bones: narrate; document; get consent; call for backup. I said their names for the camera. I asked clarifying questions. I repeated their answers back. I created a chart note out of the worst moment of my life.

The ER That Wasn’t Mine

There is a particular shame in being wheeled into your own ER. Your badge isn’t on your chest, but everyone knows where it lives. Every room has held a day of your life. The OR nurses are polite with their eyes because they’ve seen you tired and they’ve seen you brilliant and now they’re seeing you as a patient in a gown where your dignity gapes.

Rachel was the first familiar face I saw—a lighthouse in scrubs, hand warm on my arm. “You’re okay,” she said, and even if that wasn’t yet true, I believed her for long enough to keep breathing.

Surgery is never the whole story. It’s the punctuation mark. The sentence is what you do with your body after, how you teach it to trust you again. Physical therapy was a grind that had its own music: bands snapping, metronome clicks, James saying, “Again,” in a voice that brokered no pity. The first time I balanced on that foot with my eyes closed for three seconds, I cried hard enough to fog the room. No one applauded. James handed me a tissue and said, “You’ll do five seconds next week.” He was right.

The Case That Built Itself

If you live long enough around hospitals, you develop a sixth sense for which outcomes are inevitable and which ones are still in play. The case against my family felt inevitable. Not because of anger—anger is a weather pattern that moves in and out—but because the evidence didn’t require interpretation.

The prosecutor, Daniel Ooa, had a way of laying out facts like instruments on a surgical tray—each one gleaming, the purpose of each one plain. He never raised his voice. He never performed outrage on my behalf. He didn’t need to. The recording performed itself.

When the defense tried to argue duress, the judge scarcely looked up. “She recorded in a shared living space on her own device,” she said. “Motion denied.” When Madison’s attorney floated the theory that I had planned the whole thing, Daniel didn’t even object. He let it hang in the air like smoke until it dissipated for lack of oxygen. Planning would have meant I expected my sister to pick up a hammer. Planning would have meant I underestimated how fast the police could respond when someone who loves you calls 911 and says the words that move mountains: She is being hurt right now.

I took the stand. I told the truth like a nurse gives report—chronological, spare, without embellishment that could look like theater. “Did you provoke your sister?” the defense asked.

“I responded to questions,” I said. “I documented what was being said.”

“Did you ever consider that your parents might have meant well?”

“My parents wanted me to commit fraud and surrender a medical fund for a child with a documented disability,” I said. “If that is their definition of meaning well, then we are using different dictionaries.”

The jury watched the video twice. I didn’t watch them watch it the second time. I watched my hands folded in my lap and thought about how the body knows how to sit still even when the mind is pacing.

The First Colors

In the recovery room in Boston, when Emma said the word “colors,” the sound broke something open in me that had been held shut by long practice. She touched my face and laughed that bubble‑up laugh that had been mostly sound and now was also a little sight. “Blue,” she guessed, tapping my shirt. It was green. We decided that for a week, everything she named could be right if her joy said so.

Dr. Richardson didn’t promise anything more than he could ethically promise. “Neural pathways are stubborn,” he said during our consult. “They like what they know. We’re going to ask them to consider new information.”

“Neurons are as stubborn as their owners,” I said. “We’ll keep asking.”

In the hotel after surgery, Emma fell asleep to the sound of my voice reading a book she loved when the world was only tactility and sound. Now, she kept stopping me to ask questions about what pictures looked like. No one tells you how athletic hope can be. It leaps, it stretches. It gets sore and shows up again anyway.

Derek sat in the armchair by the window with his head tipped back and his eyes closed—his hand still looped around mine by reflex. We weren’t a couple anymore. We were the parents of a child who was learning the shape of light, and for that, we were solid.

Letters That Didn’t Get Read

Mom’s apology came typed and thick with words that had learned nothing. “I am heartbroken,” she wrote, as if heartbreak were something that had happened to her, like a slip on black ice. She said she didn’t recognize herself in the video. That, at least, was true. You can live a whole life never recognizing what you look like to the people you expect to love you anyway.

I slid the letter back into its envelope and wrote “Return to sender” in a hand that didn’t shake, then placed it in the outgoing mail. Closure is often administrative.

Dad didn’t write at all for months. When he finally did, it was a list of things we could do to “move forward as a family.” Every bullet point was something I had already done alone: therapy; savings plans; scheduling; forgiveness. Forgiveness showed up twice, like repetition might make it practical. I let that letter join Mom’s in whatever dead letter office holds words that never should have been written.

Madison gave an interview from jail to a local reporter who had not done enough homework to realize he was stepping into a story that didn’t want him. “My sister overreacted,” she said to the camera, eyes wet in a way that had gotten her out of trouble since she was small. “This is all very blown out of proportion. We’re family.”

The camera did her no favors. Her meanness had nowhere to tunnel now. It lay on the surface of her face like a rash the makeup artist couldn’t cover.

Aunt Carol and the Archive

When Aunt Carol reached out, I said yes to coffee because I was tired of silence that only taught me the shape of a hole. She arrived ten minutes early and sat facing the door, a woman who had spent decades waiting to be allowed back into a story that kept insisting she was the villain.

“I should have called you,” she said, fingers worrying the sleeve of her sweater. “I tried once when you were thirteen. Your mother threatened to sue me for interference.”

“That sounds like her,” I said. I didn’t mean it as a kindness.

Carol told me about my mother before my mother had daughters to triangulate. About the fiancé with a family whose money came with rules. About the stores that had let her go for small thefts she renamed mistakes. About the way she glowed around men who made her feel like the world owed her a pass. “She picked Madison,” Carol said softly, “because Madison was a mirror. She picked you for responsibility.”

“You mean she assigned me responsibility,” I said.

Carol nodded. “She always needed a straight man for her comedy routine.”

I didn’t forgive my mother in that café. I didn’t reconcile with Carol. I listened and I let the facts rearrange the furniture in my memory until rooms I’d been tripping through made more sense. I left with Carol’s number and the understanding that history had not begun with me. That’s a relief you don’t know you need until it’s handed to you across a table.

Work, Which Is to Say, Worth

Back at the hospital, patients became my clean antidote to the part of my brain that wanted to loop. A man the age my father had been when he taught me to ride a bike squeezed my fingers while I taught him to breathe through a dressing change. A new mother who had watched her birth plan dissolve in operating room lights cried into my shoulder and I didn’t pretend not to cry back. A teenage boy with a fresh scar down his chest asked if he’d ever feel normal again and I told him the truth I was learning: normal isn’t a place you get back to; it’s something you build after.

In the break room, Rachel taped my victim impact statement to the wall and marked up punctuation with a pink pen. “This comma is doing too much,” she said. “Let it rest.”

In court, when I read the statement, I kept the commas Rachel saved and used them like stepping stones to move across a river without falling in. I told the judge that my daughter had been called useless in the room where I grew up being told how to behave. I told the court that my sister’s hand on a hammer had been the last chapter, not the first. I asked the court to make it clear that what happened to me was not a private matter but a public harm punished publicly because children watch what we decide to tolerate.

The judge, who had a way with words that told me she wrote her own decisions, listened with a face that didn’t tell me what I wanted to know. Judges don’t mother you. They shouldn’t. When she spoke, she spoke like a person who understood that mercy without accountability isn’t mercy; it’s a permission slip. She did not hand one out that day.

The Internet, Reluctantly

I declined interviews because I didn’t want to be turned into a lesson plans’ “real‑life example.” Still, the recording traveled. That wasn’t mine to control once it entered the bloodstream of the culture. I set my social media to private and installed a filter on my email that sent anything with the word “exclusive” straight to trash.

But I read the notes strangers sent to a PO Box Marcus set up for me when the internet got loud: a grandmother in Idaho who had raised a blind granddaughter and wanted me to know that there would be days of exasperation and days of raw joy and they would both be true; a paramedic in Ohio who wrote that she kept a copy of my case summary as a reminder that “domestic” doesn’t mean “less dangerous”; a man who apologized for the way he used to make jokes about people with white canes and then included a check that made me cry in a grocery store parking lot. I let those notes in because they were small handrails in a stairwell I was still climbing.

Emma’s School and the Geometry of Progress

At Emma’s new school, progress wasn’t measured by a single ruler. It was circles and arcs and the angles her body made when she learned a new way to move through space. She learned to read large print and kept up her braille. She learned the difference between a shadow and a shape that held. She learned that when she couldn’t see something yet, she could ask for more light, more time, more description.

One afternoon, she came home and described the way the afternoon sun made a stripe on our hallway carpet and how the stripe moved across the baseboard as the day let go. “It’s like the house has a clock inside its skin,” she said. I put my hand on the wall and agreed.

We practiced crossing streets with a mobility trainer, and Emma laughed nearly the entire time, which is the sound you pray for when the world is full of cars and you are teaching a child to trust a rhythm she can’t always see. When she hesitated, she didn’t pretend; she said, “I need to try that again,” and we did.

The Body Remembers, and So Do You

Recovery is boring by design. No one tells you that enough. It’s bands and ice and exercises you do while the kettle boils. It’s sleeping with a pillow under your calf even when you think you’re fine because fine lies. It’s confessing to James that you ran two blocks to catch a bus and your foot barked at you afterward and he says, “Of course it did,” in a way that makes you feel like you didn’t fail; you just asked a healing body to remember its old life too soon.

But boredom is how the extraordinary sneaks in. The first evening I stood at the stove and realized half an hour had gone by without my foot chattering like a toddler needing my attention—that was a night I allowed myself to exhale the kind of exhale you only get when you’ve been holding steady through a storm.

On a Saturday morning, Emma and I baked muffins by feel and sight together. “Blue,” she said, pointing at the mixing bowl. “That’s blue.” It was stainless steel and catching sky through the window. “Close enough,” I said, and we both laughed. We were both learning how to call things by names that belonged to us.

The Day of Sentencing

The courtroom was colder than it had any reason to be. Courthouses do that—ask for sweaters in August. Madison’s lawyer touched her elbow and made a motion with his head that meant now is the time to look sorry. Madison tried. The muscles around her eyes didn’t remember how. My mother wore beige like a prayer. My father looked tired in the way men look tired when their version of events has finally found its limit.

The prosecutor restated the facts without theater. Daniel didn’t need to. The judge had the video cued in her mind like a song she never wanted to hear again but knew by heart. When the sentences came, they landed with a weight that didn’t bounce.

I didn’t look at my family as deputies guided them out. This wasn’t my moment to perform. I looked at the court reporter’s hands instead—how they flew and landed and flew again, making a record that would outlast all of us. I thought about how the body learns a skill until it looks like language.

After, in the hallway, Rachel hugged me with her entire spine. Marcus shook my hand like a colleague. Derek leaned his shoulder into mine like we were on the same team again, which we were, even if the roster had changed.

What Justice Is, What It Isn’t

People like to ask if justice felt like revenge. It didn’t. Revenge is a firework—loud, brief, flaring out. Justice is a streetlight. It turns on because the law says it should and then it keeps the corner lit whether anyone is watching or not. We walked home under that light.

Preparing for Boston, Again

Dr. Richardson believes there’s more to give. Neural plasticity is a stingy landlord, but it renegotiates if you keep paying attention. We have another procedure on the calendar. Emma has a chart on her wall where she’s drawn rows of boxes to check off the days until we board the plane. “I’m going to see the world sharper,” she says. “I’m going to see your face sharper,” I say back. We are both right.

I am better at packing now: compression socks, the travel pillow that doesn’t leave me with a crick, snacks Emma can identify by shape and sound, a list of questions for the pre‑op nurse I keep adding to even though I will not get through half of them. Nurses make lists. We also know how to throw them out when a human being needs us more than a plan does.

Boundaries as Infrastructure

The restraining order paperwork lives in a folder labeled HOUSEHOLD in the filing cabinet, because boundaries are part of how a house stands. The recording lives in three places—the cloud, a thumb drive in a safe, a copy with Marcus—because memory is fragile and I don’t intend to argue with anyone about what did and didn’t happen.

Sometimes someone asks if I’m afraid they’ll try to come back into our lives. I’m not afraid. I’m prepared. Fear is a poor architect. It builds rooms with no windows. Preparedness knows where the exits are and makes sure the path is clear.

On Raising a Child in the Light

We teach Emma that people are complicated and that complexity doesn’t obligate us to tolerate harm. We teach her that asking for help is what strong people do when they’re in a new landscape. We teach her that the world is full of accommodations because the world is full of people, and the point of a world is to make room.

On a Thursday evening, she sat at the table and drew three lopsided circles and a rectangle with a line and said, “Family.” “Who’s who?” I asked. She pointed to the rectangle with the line. “That’s the house,” she said. “It holds.”

It does.

The Long, Quiet Middle

There is a part of every drama where the credits don’t roll but the music quiets. This is where the work happens. I learned to enjoy it. I learned to admire my grocery lists. I learned to trust the way my body talked to me, not as a betrayer but as a partner. I learned that I can say no and the sky doesn’t fall. It just keeps being sky.

Rachel and I developed a ritual: on the anniversary of the day of the nail, we don’t mark the violence. We mark the call. We meet for breakfast at the diner across from the hospital and we toast with diner coffee to the words that changed everything: Emergency. Call 911. When we clink mugs, we are not celebrating pain. We are honoring response.

What I Didn’t Lose

The list is longer than the list of what I did. I did not lose the ability to believe strangers wanted to help. I did not lose my career. I did not lose Emma’s trust. I did not lose the particular stubbornness that makes a nurse a nurse and a mother a mother. I did not lose the music in my house. I did not lose the part of me that remembers how to rest.

What Comes Next (Which Is to Say, More of the Same)

There will be more appointments. There will be days when Emma’s progress plateaus and she huffs and says, “It’s not fair,” and she will be right and we will eat ice cream anyway. There will be IEP meetings where I will bring a binder and a pen and the composure of a woman who has already done harder things than advocate for a schedule that includes more braille and more PE. There will be mornings when the scar aches and I choose the shoes with more support and no one applauds and I go to work and that is a victory worth recording only to myself.

There will be a day when Emma asks to watch the video because she will understand that her mother’s scar and her own vision are chapters of the same story, and on that day, I will ask her what she wants to know first. Then I will tell her, carefully, that some people mistake love for ownership, and when you refuse to be owned, they will call you cruel. The truth is the kindest thing I can give her.

The Call, Revisited

I think sometimes about how that first call used the word “urgent” like a crowbar. “Please, we need you here this instance. It’s urgent.” The urgency turned out to be their desire. It turned out to be a trip to Cancun and a daughter’s medical fund and a belief that my life could be pried open with the right tone of voice. I catalog the other urgencies now: Emma’s laugh when she gets a joke mid‑sentence; the smell of rain that tells me to bring the cushions in from the porch; the text from Rachel that says, “Lobby in two minutes?”

Urgent used to mean a house that would swallow me whole if I didn’t keep the floor swept and my voice level. Now it means what it always should have: pay attention; this matters.

A Note on Mercy

I don’t wish my family harm. That’s not the same as wanting them back. I hope Madison learns something in the long grid of days ahead that sticks to her ribs and changes her mouth before she opens it. I hope my mother discovers what it feels like to tell the truth without spinning it into a costume. I hope my father learns the difference between disappointment and principles. None of that is my work. My work is here: a child, a job, a life that keeps its promises.

The Scar, Unhidden

The scar is not a secret. I don’t cover it unless I’m cold. When new nurses on my unit notice it and hesitate—curious but cautious—I tell them the short version. I tell them that sometimes the people who love you do something unspeakable and then argue with the grammar. I tell them to document, to call for help, to trust that the same spine that holds them upright through a 14‑hour shift will hold them upright when the room is a living room and not a trauma bay.

On an evening in late fall, Emma and I sat on the porch steps and she leaned her head against my shoulder and said, “It’s darker earlier now.” “That’s what the season does,” I said. “It comes, it goes.” We stayed until we needed sweaters. We went inside. We turned the lights on. We kept the house we made lit.

Coda: A Checklist

Because I am a nurse and because I am a mother and because both of those jobs are full of lists, here is mine, in no particular order, for the next year:

– Keep the fund growing.

– Keep the appointments.

– Keep the boundaries.

– Keep laughing with Rachel in hallways.

– Keep thanking James when he makes me do hard things and then do them.

– Keep sending Marcus every document he asks for before he asks.

– Keep listening when Dr. Feldman asks questions I don’t want to answer and answer them anyway.

– Keep taking pictures even on days Emma sees them as shapes.

– Keep deleting emails that ask for exclusives.

– Keep refusing to read letters that mistake performance for apology.

– Keep sleeping.

– Keep the lights on.

And finally:

– Keep choosing the kind of urgency that builds a life, not the kind that tries to borrow it.

When I mark the days off on the calendar toward our next Boston procedure, I think about how ordinary all of this looks written down. Flights booked. PTO requested. Childcare coordinated for the nights Emma wants to sleep in her own bed and then changes her mind at bedtime. Ordinary looks like surrender until you realize it’s a decision. I choose it every morning, on purpose.

The phone is quiet now. When it rings, it is rooms I want to enter. When I pick up, it is voices I chose to keep. If a number I don’t recognize flashes onto the screen one day and a familiar voice says, “Please, we need you, it’s urgent,” I will take a breath, look at the scar that made me honest, and reply with the only answer that has ever saved anyone: No. Not anymore. Then I will hang up, and I will walk toward the child who is learning color by color what it means to see, and together we will keep learning what it means to live.

A Year Measured in Small Braveries

Spring slid into summer as if turning a page with a careful thumb. The world did not announce itself as healed. It simply kept arriving: mail on the porch, sun through the blinds, the sound of the neighbor’s dog thumping an eager tail against a fence post at precisely 6:10 every morning. You don’t notice how sturdy ordinary is until you’ve lived without it. Ordinary is a beam you don’t see until the roof gives.

At County General, I took the early shift more often than not. My foot liked mornings better; pain is a patient tutor if you let it be, but it’s stricter after noon. James had me doing calf raises while I microwaved leftovers in the break room, a ritual that looked like penance and was actually permission: permission to walk farther, to stand longer, to trust tendon and bone again. Nurses crowded around the tiny window to the lot whenever thunderstorms rolled in. We could predict the rush by the color of the sky. We could predict our own aches by the same.

Emma kept a notebook of new things she could see, a private museum of light. Some entries were small—the reflection on the spoon is a moon if you tilt it—and some were as big as a childhood—my teacher’s shoes are red and they squeak. She let me read it sometimes and sometimes she didn’t, which felt exactly right. Seeing is not a group project. That was a lesson I had needed, too.

We went to the same playground as always, the one with the chipped green slide and the tall chain‑link fence that kept the ball on the right side of the world. Emma walked the perimeter, cane sweeping a confident arc, then looked up and said, “The sky has lines.” Contrails stitched white dashes across blue. “Good eye,” I told her, and meant it both ways.

When it rained, the scar spoke. Not a shout anymore. A clearing of the throat. I answered it with warm socks and the humility to sit down. My patients gave me practice navigating the space between strength and rest. A woman with a fresh mastectomy whispered that she felt like less. I pulled a chair close and said, “You are not an equation that lost a variable. You are the whole math.” She laughed and then cried and then asked for ice chips because bodies still have their preferences even when hearts are breaking.

School, Where We Learn What We Already Know

In September, the IEP team invited us to a table that had seen every version of worry. I arrived with a binder tabbed within an inch of its life and the calm of a woman who had already argued for a child’s future in rooms colder than this. The team was kind and prepared; most school people are. We spoke the language that makes adults feel in control: accommodations, minutes, goals. Emma sat between us and tapped her cane against her sneaker like a drummer keeping time.

“What do you want to learn this year?” the vision specialist asked Emma directly, which made me like her even more.

“I want to read faster,” Emma said. “And I want to pour milk without spilling.”

“We can work with that,” the specialist said.

Later, walking to the car, Emma said, “They asked me like I could decide.”

“You can,” I said. “You should.”

She took that in, head tilted in the new way she had developed since the first procedure—as if lining up what she could see with what she already knew by touch and sound. “I decide,” she repeated, satisfied by the feel of the words in her mouth.

Letters That Still Arrive

Every few months, a new envelope made its way to my mailbox with my name in handwriting that pretended to be neutral. The prison return address told the truth the handwriting tried to hide. The first time one came addressed to Emma, I took a walk around the block to let the surge pass before I put it in the shredder. Anger is a useful fuel. It is also corrosive. I try not to run my home on it.

Marcus kept me updated when updates mattered and left me alone when they didn’t. “Appeals will appeal,” he said dryly, sliding a sheet across his desk for my signature. “The decisions stand.” He didn’t say for now because he understood how that phrase turns a life into a waiting room.

Aunt Carol wrote twice. The first letter told me she’d started volunteering at a community center library, shelving donated paperbacks and helping teenagers fill out job applications. “I thought I was done with rooms that require my very best patience,” she wrote. “Turns out patience is a muscle I don’t want to lose.” The second letter included a photo of her in a cardigan with coffee stains on the wrist, grinning in front of a cart. Progress takes the shape of a book truck sometimes.

Work, Made Holy by Repetition

I signed charts. I taught an anxious gentleman how to use an incentive spirometer and celebrated like he’d climbed a mountain when he hit the little mark we set. I argued with an insurance case manager until she said yes because sometimes advocacy sounds like stubbornness with good manners. I flushed a PICC line while a teenager asked if the scar would ever stop being the first thing strangers saw. “It won’t,” I said. “But you can decide what story they hear about it.” He nodded like that was a concept he could live with.

Rachel and I ate lunches on the courtyard bench under a tree that produced more leaves than seemed strictly necessary. We made fun of our own gallows humor and then forgave ourselves for it. People who work with the body’s messiest truths need humor like divers need air. “On the anniversary,” she said, “diner?” It had become our ritual: the breakfast that honored the call that started everything. We split a short stack; we toasted with coffee. We did not talk about blood.

Preparation Is Its Own Kind of Peace

The Boston folder lived on the fridge with magnets that had lost their vigor and slid down unless you placed them just so. The list inside grew and contracted with the tide of practicalities. Compression socks. Doctor’s questions. Shuttle schedule. Emma had added her own items in loopy print: gum for ears popping, the good blanket, Mom’s funny face for when I’m scared. I practiced my funny face in the bathroom mirror and startled myself into laughing, which I decided counted as training.

We did not promise miracles. We promised lunch at the little place near the river after pre‑op. We promised to narrate the art in the hospital lobby. We promised to tell the truth to each other in words the other could carry.

On the night flights were booked, Emma taped a paper airplane to the calendar square for departure. “So it knows,” she said.

Boundaries, Boring and Beautiful

People like their stories to swing shut with a bang. Mine closes with the soft click of a well‑fitted door. The restraining order form stayed in its folder. The recording stayed in three places. I don’t take unknown numbers. If a message matters, it leaves a message. Very little matters that much.

At first, I told new people in my life a short version: parents, sister, video, court. The more I said it, the less I wanted to. Not because I was ashamed. Because I was busy. Busy is not avoidance when the business is building a life.

Jennifer—Derek’s wife—learned the recipe for Emma’s favorite soup and dropped off a pot on days when I looked more tired than I was willing to admit. It is a strange grace to be fed by the woman married to the man you used to love. It is also a proof: families are made, not discovered.

The Visit That Didn’t Happen

In late winter, a letter arrived with a request for a visit. Not from my mother. Not from my father. From Madison. It was two sentences long, a brevity that might have read as humility if I didn’t know her. “I want to talk,” she wrote. “This has gone too far.”

I placed the letter back in the envelope and set it on the counter, meaning to think about it. I made dinner, ran a bath for Emma, answered a text from Rachel. Later, when the house was quiet, I returned, picked up the envelope, and put it through the shredder. It was not a grand gesture. It was a small one. Not every refusal needs an audience.

I told Marcus the next day. He nodded. “If she tries to contact you again, we’ll file. But that”—he gestured toward the air where the shredded paper used to be—“that’s a perfect filing, too.”

The Day We Practiced Seeing

On a Saturday, we went to the art museum because I had a coupon and Emma’s teacher had given her a list of pieces with high contrast. “We’ll do it small,” I told Emma. “Two rooms. Snacks in the middle.” She agreed to the terms like a tiny lawyer.

We stood in front of a painting blue enough to be a dare. Emma stepped close, then closer, then checked with the docent that it was okay to stand that close. “It’s like the ocean,” she whispered, “but without the cold.” I watched her watching. The docent smiled and said, “People cry in this room for all kinds of reasons.” I nodded without apology and wiped my face with the sleeve of my sweater because some moments prefer practical dignity.

In the sculpture room, Emma traced the air above a bronze hand with her own. “It’s like it’s reaching,” she said. “For what?” I asked. She considered. “For more.”

We ate pretzels in the atrium afterward and I wrote museum on the Boston list because sometimes practice is the best packing.

Court Without a Gavel

Emma asked one evening if prisons had libraries. “They do,” I said. “Some are very good.”

“Do people change when they read?” she asked.

“Sometimes,” I said. “If they want to.”

She thought about it, then nodded, then returned to her homework. I sat a little longer with the question than she did. Aunt Carol’s letter had included a statistic about recidivism and reading. I didn’t know what I wanted for my mother and father and sister beyond distance. Some days, I wanted them to change out of principle. Some days, I wanted them to feel every empty minute they had given me. Most days, I wanted breakfast on the table and for Emma’s favorite socks to be dry by morning. Justice looks different depending on the light you stand in.

The Day the Phone Rang

It rang on a Thursday while I was making spaghetti, and all the hairs on my arm stood up the way they do when thunder rehearses. Unknown number. I let it go to voicemail and finished stirring the sauce. Emma grated parmesan with her careful new confidence and said, “You’re breathing like you’re running.”

“I’m reminding my body where we are,” I said.

Later, after dishes, I listened. A voice I hadn’t heard since I was a teenager, a neighbor who used to hand out full‑size candy bars on Halloween, wanted to know if I might be willing to come speak to her church group about “forgiveness and family.” I smiled at the couch, at the blanket thrown crooked over its arm. “No,” I said, not into the phone but into the room, which was the only place that needed the answer. Then I deleted the message and we played a board game whose rules Emma liked because they made sense and still let luck through the door.

The Night Before the Flight

We packed like we were moving across town: deliberately, with a map in our heads of where everything would go when we reached the hotel. Emma laid outfits on the bed and chose, to my surprise and delight, a sweater I loved and she used to refuse because she couldn’t see the pattern. “It’s like squares,” she said, palms moving across the knit. “But with waves.” I kissed the crown of her head and did not cry because I wanted her to remember the room as a place where choosing clothes was routine, not sacred.

Derek texted to say he’d pick up the car from the mechanic while we were gone and that Jennifer had left a casserole in the freezer. Rachel sent a picture of the diner mug waiting for our return. Marcus reminded me to photograph every receipt, which made me laugh until I did as I was told and made a folder on my phone labeled BOSTON 2, even though naming it like a sequel made my stomach lift and then settle.

In bed, Emma whispered in the dark, “What if it doesn’t help more?”

“Then we’ll still have what we have,” I said. “Which is already a lot.”

“What if it helps a lot?”

“Then we’ll learn that, too.”

She took that in the way only a child can—completely and for now. She fell asleep with her hand on my arm like a promise and I lay awake for a while, listening to the house know our weight and be pleased by it.

Gate A12, Where the World Gathers

Airports are the closest thing America has to a cathedral—everyone is on their best behavior and worst behavior at once, and the announcements make you feel like you belong and like you will be punished if you don’t. Emma loved the moving walkway like a theme park ride and I let her, which felt like both a treat and practice in spending joy carefully.

We bought gum. We bought a bottle of water so wildly expensive it felt like performance art. We sat at Gate A12 in a row of seats that had seen a hundred small dramas. Emma leaned into my side and narrated what she could see: a pilot’s hat with a silver badge, a toddler’s bright shoes, a man with a book held very close to his face who was mouthing the words. “He’s practicing,” she said, recognizing a cousin in someone else’s effort.

I didn’t text anyone from the gate. I had learned my lesson about making the world an audience for moments that belonged to us. I did take a picture of our knees in their matching jeans because someday, when she is older, I want proof of the ordinary.

When they called preboarding for passengers who “need a little more time,” Emma looked at me. “Do we?”

“We can,” I said. “We don’t have to.”

She considered. “Let’s just go regular,” she said. “We’re good at lines.” And we were. We are.

The Seatbelt Light and the Long View

Up in the clean air where the world stops pretending it can control anything, the city looked like a board game. Emma gripped my hand at takeoff, then loosened, then gripped again. “It’s like a zipper,” she said as the plane banked and the light shifted across the wing. The woman across the aisle smiled, and I did not mind her listening. There are witnesses you don’t resent.

I didn’t sleep. Mothers don’t sleep the night before, even when the night is daytime above the clouds. I read the safety card like it held poetry and answered Emma’s questions about oxygen masks as if we were practicing for a school quiz.

When the wheels hit the runway in Boston, Emma clapped once and then put her hand over her mouth, embarrassed. “Everyone wanted to,” I whispered, and she laughed.

Check‑In, Checklists, and Choosing Peace

The hotel room smelled like lemon and ambition. We put our things in drawers like we would be staying forever because rituals comfort bodies that are about to be asked to do something difficult. I taped the schedule to the mirror. I taped Emma’s drawing—a rectangle for the hotel, a lopsided heart for us—next to it. We ate the good blanket’s weight across our laps and watched the local news talk about traffic on the Mass Pike like it was weather.

Dr. Richardson’s pre‑op team was as kind as memory and exactly as efficient. “Same drill,” the nurse said, checking boxes with the style of a woman who had never needed glitter to be effective. Emma listened to instructions with the attention she saves for adult voices that speak to her like she is a person, not a patience exercise.

Back at the hotel, Rachel texted a photo of the diner mug and a caption: Save me a window story when you get back. Derek sent a picture of our porch light turned on. Jennifer sent a reminder to wear the compression socks on the flight home even if you hate them. Marcus, bless his lawyer heart, texted a single thumbs‑up, which in his language meant I am holding a line you will never have to see.

The Night Walk

We took a short walk along the river because the weather asked us to. Emma held my elbow as the wind lifted her hair. She named what she could: light on water, a runner’s neon shirt, the way a dog’s leash drew a straight line that pulled and then slackened. “It’s a graph,” she said, delighted to have found math in motion. “X‑axis, Y‑axis, dog.”

“Exactly,” I said, and meant it like prayer.

We stood on a small footbridge and watched the city pretend to be still. Emma took my phone and held it up, squinting, then laughed. “I can see a little more than last time,” she said. “It’s like the world got a new pencil.”

“We’ll sharpen it if we can,” I said. “And if we can’t, we’ll use the one we have and make great things with it.”

“Great things,” she repeated, content.

Morning, and the Only Promise I Can Make

The morning of pre‑op arrived like all mornings do—indifferent and generous. Emma ate half a bagel and declared it sufficient. I drank coffee and pretended it was courage. We walked to the hospital because moving our bodies felt like the right first sentence of the day.

In the lobby, a volunteer played a piano like he was inventing calm for anyone who needed it. Emma leaned on the cool marble and named notes she recognized from music class. I signed forms. I signed my name so many times my hand learned to do it without supervision.

“Ready?” Dr. Richardson asked, and Emma nodded with the authority of someone who had decided.

“Ready,” I said. I wasn’t lying. Readiness isn’t lack of fear; it’s willingness to walk while afraid.

We rode the elevator up. The doors opened. The hallway smelled like antiseptic and new beginnings. Emma looked up at me and said, as if it were the first time and not one of many, “Mom?”

“I’m here,” I said.

I will be.

Epilogue: The Call Redefined

There will be other calls in my life. I know that. The ones I keep will be the kind that sound like this: “Mom, I did it!” from a classroom where she learned to pour milk without a flood; “Are you free?” from a friend in a parking lot with two coffees and a story; “Your patient’s family wants to say thank you” from a hallway where I am halfway to the next room and can turn back for hugs without losing the thread of who I am.

If another voice from the past ever says, “Please, we need you here this instance—it’s urgent,” I know exactly what urgent means now and who gets to define it. My answer will be the same as it was the day I finally learned my worth is not a bargaining chip: No. Not anymore.

Emma’s laugh is the only siren I follow without thinking. The rest of the world can leave a message.

We will fly home when the doctors say we can. We will eat soup at our own table with the light low and kind. We will sleep like people who have done the hardest part of the day. And if the house creaks and the scar speaks and the wind tells stories against the window, I will let the sounds pass through me and keep only what I need: the knowledge that I built a life that holds, that my daughter can see me enough to find my face in a crowd, that in a world where “urgent” gets thrown like a rope, I chose which lines to catch and which to let fall.

That is the ending and the beginning both. The rest is practice. The rest, finally, is ours.