At 11:51 p.m., my phone lit up the way truth does—sharp, merciless. A message from my mother: We’ve agreed. You’re no longer part of the family. Don’t come to any gatherings. No call, no hesitation. Just a digital exile. Seconds later, my sister hearted the message like betrayal was a team sport.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t ask why. I opened my laptop and signed into the accounts I’d kept afloat for years: mortgage, utilities, car insurance, HOA dues, even the streaming bundle my parents insisted they didn’t know how to cancel. Click. Cancel. Click. Remove payment method. Click. End autopay. By 12:03 a.m., their world started to flicker in the dark, and my apartment went very quiet, the kind of quiet that makes the hum of the fridge sound like a witness and the tick of the wall clock sound like evidence.

Anger wasn’t loud this time. It was clinical. For years, I had been the silent investor in their version of family—the person who answered when the caller ID said HOME, the saver of Thanksgivings, the fixer of overdrafts. I told myself it was love. Responsibility. The right thing to do. Now I could see it clearly: it had been a subscription, and I was the one footing the bill.

My name is Sophia Johnson. Chicago winters raised me as much as my parents did. I grew up counting quarters at a kitchen table that wobbled, the kind you steady with a folded flyer. The apartment on Belmont had a radiator that coughed like a smoker and windows that sweated in February, and it had my mother, Linda, who could turn guilt into a marinade and baste you in it all year. Small portions served often. My father, Thomas, perfected the art of absence—you couldn’t accuse him of shouting because he rarely spoke. And my sister, Kayla, was kinetic sunlight: loud, charming, allergic to consequences.

The first time I paid their property tax, I was twenty-six and terrified of my own rent. Foreclosure notice. Panic over the phone. My mother’s voice cracking. “You’re our guardian angel,” she said when I wired the money. I believed her. Then came the gas bill in January, the car insurance in April, the “surprise” tuition gap in August—eighteen thousand a year for three years, all because Kayla “couldn’t focus on finals with a part-time job.” I told myself this was what family did: shoulder the weight and call it love. Funny how angels always end up footing the bill in hell.

At a Sunday dinner six months ago, I learned the table had never been a table; it was a courtroom. My mother corrected my posture as if I were twelve. Kayla bragged about an “international business trip” that I happened to know was a week at a resort in Tulum. My father tilted his glass and joked, “Soph’s too serious to keep a man.” I smiled past the mashed potatoes, swallowed the truth, and offered to help with dishes I hadn’t dirtied. That night on the train home, I watched my reflection shake in the window as the tracks hammered underneath, and I thought: next time I’ll say something. Next time I’ll set a boundary. But boundary is a word you only learn after you’ve been trampled.

When the exile message came, I didn’t try to translate it into something gentler. I took it as minutes. I opened a spreadsheet. Date. Amount. Reason. Proof. I scrolled through years of transactions, flagging every time I had papered over their chaos. The overdraft fees when Dad “borrowed” my card for gas. The ACH pulls when the mortgage autopay failed and my account became the net. The transfer to Kayla when she forgot tuition was due and texted me a crying selfie from the library bathroom. Line after line, memory became math. Math has a way of making you honest.

By morning, my phone was a museum of missed calls. Dad. Mom. Kayla. Each name glowed like a relic of something that used to matter. I didn’t answer. The silence between us had weight now; it wasn’t a void, it was a wall. The first text to slip through wasn’t even from my mother. It was Kayla: You’re overreacting. Mom didn’t mean it like that. Can we just talk? I read it twice. No apology in it—just control dressed up as concern. Delete.

At 9:00 a.m., an email arrived from my mother. No greeting. No apology. Subject: Situation. We need to talk about what you’ve done. You’ve created a mess. Call us immediately. Not a word about the exile. Not a breath of accountability. Just a summons back to the role I’d performed for years: fixer, buffer, peacekeeper. I typed: I’m busy reconciling accounts. You should do the same. Send.

By noon, panic became a chorus. Dad: Can you please explain what’s going on with the utilities? Your mother’s losing it. Kayla: Why are you doing this? You’re ruining everything. Ruining everything. As if my silence were the crime, not their verdict. I opened my banking app and watched years of my life scroll past in little gray rows. Something shifted. The guilt tattooed into my bones began to fade. Precision took its place—cold, deliberate, focused.

At 3:00 p.m., my mother posted a vague update on Facebook: Some people forget who raised them once they start making money. Pride comes before destruction. Thirty-something likes bloomed under it, mostly from relatives who hadn’t spoken to me in years. I didn’t respond. But I took a screenshot and filed it in a folder labeled: Narrative.

At 6:00 p.m., I called Julia. We met freshman year at UIC when my Econ class shared a wall with their debate team, and her voice has sounded like a lifeline ever since. Now she’s a family-law attorney who specializes in messy inheritances and the legal knots people tie around their own hearts. “I think I’m done playing accountant,” I said. She didn’t ask for a monologue. “Then start documenting everything,” she replied. “We’ll make it official.”

That night, my living room became an evidence room. I pulled emails out of years, stacked PDFs like bricks, titled folders with dates, labeled screenshots with names. My grandmother’s trust documents. The refinance closing packet with all those pages I’d signed to “help” my parents lock a lower rate. The deed I never transferred because something in me—call it paranoia, call it a whisper—had said, Not yet. The more I organized, the lighter I felt. By midnight, my inbox looked like a courtroom where the judge finally had eyes.

On the second night, the quiet grew a rhythm. The city outside pulsed with its own heartbeat—sirens in the distance, a bus sighing at the corner, the blue wash of a TV through someone else’s blinds. In my apartment, the glow belonged to my laptop. Mortgage. Insurance. Tuition. Taxes. Every tab was a door into a room I had paid to keep warm while standing in the hall. At 11:00 p.m., Julia called. “Everything ready?” “Every receipt,” I said. “Every transfer.” She exhaled like a boxer between rounds. “Good. Then you’re not asking for repayment, Sophia. You’re enforcing it.”

She dictated the language like a metronome: Subject line—Outstanding balances, Johnson family account. Body—This email serves as formal notice of reimbursement due for payments made by Sophia Johnson on your behalf from 2016 to present. You have thirty (30) days to initiate a repayment plan before legal action is taken. Attach: ledger, copies of receipts, highlighted bank statements. No anger. No threats. Just business English, the kind that makes people sit up straighter. When I hit send, the silence that followed didn’t feel empty. It felt alive.

Twelve minutes later, the first response arrived. Dad: Let’s be reasonable. Mom: How could you do this to us? Kayla: You’re insane. You’re ruining the family. I read their words with a steadiness that felt borrowed from someone older, someone wiser, someone who understood that a boundary is a door you can close without explaining what’s on the other side. They weren’t shocked by what they’d done. They were shocked that I’d stopped playing along.

At 12:03 a.m., my phone lit up like a crime scene. Calls. Messages. Voicemails. “Turn the lights back on,” my mother shouted into one, her voice cracking. “We’ll fix this tomorrow.” But tomorrow had already arrived, and they were the ones in the dark. Julia’s email cut through the noise: Perfect. Forward everything. We’ll file a demand letter first thing.

Two days later, Julia sent me an email with the subject: Additional discovery. Attached: bank screenshots, a PDF labeled TRUST—BENEFICIARY CHANGE, a neat little note from a probate office in New York—Patterson & Low. The paralegal there, Amy Patel, had flagged “discrepancies” in my late grandmother’s estate. In other words: somewhere between the reading of Ruth Johnson’s will and the remodel my parents bragged about, a signature had been bent into the shape of my name.

I read the email three times. The kitchen tile. The marble counters. The timeline aligned with the precision of spite. The “withdrawal” tagged for “house improvements” matched an amount I recognized: forty thousand dollars. The signature next to it was not mine.

“Forgery likely,” Julia’s note read. “We’re filing for an injunction.”

By evening, the court had frozen what could be frozen, and my mother’s Facebook became a theater of self-pity. She posted a photo of a sunset over their cul-de-sac and wrote: We raised her with love and she turned on us for money. Pride, pride, pride. The comments were a chorus. But then something new appeared under the hymn: a question from my cousin Leila, who is allergic to both drama and lies. Wait, didn’t Sophia cover the house after foreclosure? And isn’t she still on the deed? The thread thinned to silence. There is a certain sound to the moment the story people tell about you stops working. It sounds like a fork dropped onto tile.

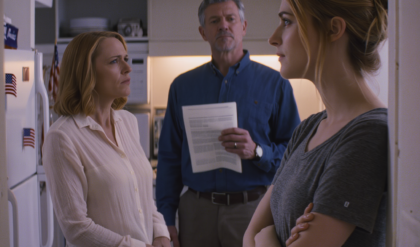

At 8:32 p.m., my buzzer snarled. Through the peephole: my mother, damp-eyed, clutching an envelope as if the paper could save her. “Sophia,” she whispered when I opened the door a fraction. “Please. We’re losing everything. Do something for your sister.”

“For Kayla?” I asked. “She’s still your sister,” my mother said, the word still doing more work than it had any right to. I passed a document through the gap: a copy of the eviction notice Julia had filed that morning. “You’ll get the official copy in seven days,” I said.

Her face drained of color. “You wouldn’t.”

“I already did.”

She searched my eyes for the old version of me—the one who fixed, forgave, funded. But I had retired that woman. “Goodbye, Mom,” I said, and closed the door. I didn’t watch her leave. I leaned my forehead against the wood and breathed like I was learning how again.

The house on Birchwood had always been more story than shelter to me. The siding was “heritage blue” because my mother believed the word heritage could be arranged like furniture. My father had framed out the garage but never finished it—he was a great starter. The maple tree out front wore a tire swing until Kayla outgrew childhood on a Tuesday. Inside, the living room had a dent in the drywall exactly at Kayla’s shoulder height, from when she insisted the prom dress didn’t fit because the world was unfair and not because she’d picked a size down for hope. Family is a museum of small damages.

When the sheriff posted the notice, I took a bus to Birchwood, walked the sidewalk like a stranger, and let myself in with a key I had kept, a key my mother once accused me of “forgetting” to return. The house smelled like lemon cleaner and defeat. The kitchen was bright with the remodel—the marble counters as pale as a lie, the subway tile so earnest it almost apologized. On the fridge, glossy magnets from places my parents had never taken me slid under the weight of a new magnet that said BLESSED.

I set a banker’s box on the counter and took only what belonged to me or to Ruth: a porcelain bluebird from her windowsill, a quilt she’d sewn from church bazaar leftovers, a jewelry box that tanged of cedar and safekeeping. The photo albums stayed. So did the framed certificate my parents hung to celebrate Kayla’s Bachelor of Arts, the one with a gold mat they bought on a payment plan. I took the copy of the original deed—the one with my signature on the line that had made it possible to lock a lower rate that Christmas when the furnace died. I left my mother’s sticky note on the thermostat that said DO NOT TOUCH in her severe cursive. You keep some relics in place so you can remember what you survived.

Closing day happened in a room with low carpet and a too-cold pen passed around a table by people who would go home and forget my name. The buyer was a woman with paint swatches tucked into her purse—a nurse, she said, who liked quiet. I signed and signed and didn’t look at my parents. The wire hit my account before I left the parking lot. Watching that confirmation line appear felt nothing like revenge. It felt like balance.

Evan helped me move. He’s the kind of friend who listens with his hands—he’ll build a bookshelf when you can’t speak. We met in a café where I did freelance invoices and he fixed espresso machines. He arrived with a dolly, a roll of blue tape, and a thermos that smelled like cinnamon. “Congratulations on your court victory,” he said with a grin, though the ink on anything legal was barely dry. We didn’t talk about my parents. We talked about the light in the new place, about the way the windows faced east and how mornings might finally stop feeling like interrogations. When the last box thumped onto the floor, he handed me a cup. “To quiet that doesn’t accuse you of anything,” he said.

That first night, after he left, the apartment was so clean it echoed. I opened my old spreadsheet—the ledger where I had turned my history into a balance sheet—and hovered over DELETE. For years, I’d believed the numbers would save me because they would prove what I had done. But proof is a bridge to a place you actually want to live; you’re not meant to keep standing on the bridge forever. I clicked. The cells went blank. And I felt something unspool inside me that had been knotted for a decade.

Word traveled the way it always does—through mouths that don’t want to be responsible for their own hands. I heard my parents were renting a small house outside the city. Kayla had taken a part-time job somewhere she hated, where uniforms were required and apologies were not. I didn’t feel triumph, only distance. They were living the life they had built without my money propping it up. Distance is not anger. It’s altitude.

Weeks turned into a quiet the size of a new continent. I slept through the night for the first time since graduate school. My mornings were mine. I stopped flinching when my phone vibrated. I bought tulips for no reason and watched them drink the room. I made a list of things that belonged only to me: this window, this mug, this stack of books, this laugh. I put the list in the drawer with the warranty for the stove.

On a Saturday, I took the train to Mount Zion Cemetery where Ruth lay under a stone with her name carved in a font she would have called fancy. The air smelled like cut grass and a little rain. I brushed leaves from the base and set the blue tulips down the way she liked them. “It’s done,” I told her. A breeze passed over my bare arms, and I thought about the last summer I spent with her when I was thirteen and she taught me how to seal jars of peaches. “You don’t leave air where rot can live,” she’d said, tipping a lid with a spooned clink. “You close it up clean.”

After the letters went out and the papers were stamped, Julia called to say the words I didn’t know I needed: “Case resolved. Repayment agreement signed. Probate reversed. You’re clear.” Clear felt like someone had opened a window in a room I didn’t realize I had sealed. I stood there with the phone to my ear and let the word drop into me like a pebble into a lake. The ripples reached places that had been still for years.

I wish I could tell you I never thought about them again. But forgetting is not a faucet. It’s a decision you make every morning until it becomes a habit your bones remember before your brain does. Sometimes I saw a woman on the street with my mother’s walk and felt my throat go tight. Sometimes a joke rolled through a room and I heard my father’s chuckle as if he were in the next chair. Sometimes a girl with a mouth like a bullet laughed too loudly on the train, and Kayla’s ghost sat down across from me and crossed her legs as if nothing had ever happened to us. I let the feeling come and go. I didn’t tell it to stay.

A month after the sale, I found a message in my inbox from Amy Patel at Patterson & Low. A scanned note in my grandmother’s hand, dated a year before she died: I intend for Sophia to have the keys to her own life. It wasn’t a legal document. It wasn’t enforceable. It was just ink on paper from a woman who wore a cardigan with holes in the sleeves and tucked cash into hymnals to give later to people she thought might need it more. But the line looped around my spine and pulled me straighter. Keys to my own life. On my way home, I stopped at a hardware store and made two copies of my apartment key. I gave one to Evan and put the other in a tin with the bluebird, the quilt, and the deed copy. A small reliquary for a new life.

Sometimes Evan and I cook dinner with the windows open and the ball game murmuring like an uncle in the next room. He asks me once, gently, if I want to talk about “the situation,” and I say, “Not today,” and he nods in a way that means: Not today can be forever if you need it to be. We make pasta. We eat on the floor because I haven’t bought a table yet, and for the first time a bare floor doesn’t feel like lack, it feels like possibility.

On a Thursday, I get an email from my mother that begins with a paragraph about God and ends with an ask for help with a deposit because their landlord is “being difficult.” I forward it to Julia and archive the thread. Later, my therapist—Dr. Levin, who looks like the librarian you trusted in third grade—says, “You are allowed to be done.” Her office smells like spearmint tea and paper. I tell her I used to think love was endurance. “Love is a vote,” she says. “We forget that. You’re allowed to stop voting for your own disappearance.”

On an ordinary morning in June, I walk past a storefront on Clark where a kid is learning to play “Heart and Soul,” and I stop because the sound of two hands finding the shape of a song feels like everything I can’t say out loud. I stand there until the music falters and starts again, and I think about my hands and all the signatures they’ve made—leases, checks, contracts, notes excusing absences, cards with ten-dollar bills folded into them. I think about the way my name used to be a promise I wrote for other people to cash. In the glass, I see a woman who looks like me. She is me. She is no one’s ledger. She is paid in full.

At 11:51 p.m. on a different night—the season turned, the air soft through the screen—I sit at my desk and open a blank document. No columns. No cells. I write the first line of a story that belongs only to me, and when the city’s hum drops to a hush, I don’t mistake it for loneliness. It is quiet, steady, earned. And if a phone lights up somewhere with a message that declares someone’s exile, I hope whoever reads it has a Julia to call, an Evan to carry boxes, and a Ruth in the ground who left them a sentence that fits on a scrap of paper but holds the weight of a house: You’re allowed to have the keys to your own life.

Sometimes people ask if I feel bad for turning off the lights. I tell them the truth: I didn’t turn off anything that wasn’t wired to me by choice. I flipped my own breaker back on. I stood in my own small kitchen with my own bills in my own name and felt the power belong to me in a way that had nothing to do with money and everything to do with finally stepping out of a story that made me smaller than I am.

On the anniversary of that first message, I walk to the lake at dusk. The water takes the sky and makes it something else. I sit on the cold concrete and watch runners slice the evening, dogs pull their people, a girl practice a cartwheel until she collapses laughing. I think about a house with a heritage-blue siding, a tire swing, a thermostat with a note on it, a magnet that said BLESSED, and I let the picture go, not because it isn’t true but because it no longer needs to be mine. I go home and sleep. The city hums. The clock ticks. The fridge sings its small, faithful song. My life keeps time with itself.

If you are reading this and feel that knife-twist recognition in your ribs, know this: you are not cruel for choosing peace. You are not heartless for asking the heart to beat for you first. You are not alone in the dark. The light you need is probably already in your hand—dumb, blunt, rectangular. A phone, a key, a pen. Use it. Turn on what belongs to you. Turn off what does not. And when the silence arrives, let it sit beside you. Give it a chair. Learn its shape. It will teach you how to hear your life when no one else is narrating it for you.

I used to believe the end of a story had to arrive with cymbals—big gestures, a grand reveal, a crowd to witness the transformation. The truth is humbler and more expensive: it arrives in the price you no longer pay to be loved. It shows up at 7:18 on a Tuesday when your coffee is warm and the inbox is quiet and your name is not being used as a battering ram for someone else’s emergencies. The great thunderclap was one message; the real ending is a thousand small mornings that don’t bleed you dry.

But endings have their echoes, and some of them ask to be heard.

On a gray April afternoon, Julia and I took the elevator to the eighth floor of the Daley Center, the two of us reflected and re-reflected in the chrome like we were being multiplied into a small army. We weren’t there for theater. We were there for continuance: a quick appearance on the probate calendar so the judge could stamp what the filings already said. I had imagined this moment like a cliff—the air thin and terrifying—only to discover it felt like a curb. You look, you step, you keep walking.

The courtroom was colder than any room that tall had a right to be, the HVAC humming like a warning. A bailiff called names, the clack of his tongue a metronome on the wood. People in suits murmured with people in cardigans; a man in a work jacket sat with his hands clasped so tight the knuckles whited under the brown. When our case was called, it was four minutes long: Julia introduced herself, spelled my name for the record, and summarized the discrepancy the way a surgeon circles a spot with a pen. The judge—a woman with kind eyes and a voice that brooked no theater—read, nodded, and said, “The order will issue.” That was it. No cinematic pause. No gasps. Just the law doing what it does when the story is straight.

When we stepped back into the hallway, Kayla appeared like she had been conjured by the word sister. Her hair was too shiny for a weekday and her eyes were red in that performative way mascara makes worse. “So this is what you wanted?” she said. “To humiliate us?”

“I wanted the truth to stop being optional,” I said.

She made a sound that used to send me running for my wallet, a small helpless gasp. “Mom isn’t sleeping. Dad’s blood pressure—”

“Your mother sent me a message at 11:51 p.m. telling me I was out of the family. Your father watched it happen. I slept fine after I stopped paying to be related to you.”

Kayla’s mouth made the shape of a curse and then rearranged itself into a plea. “We can fix this, Soph. We can go to lunch and figure it out.”

“Fixing it would require honesty and repayment,” I said. “Lunch can’t buy either.”

Julia’s presence at my shoulder was a quiet lighthouse. Kayla looked at her the way people look at tow trucks when they block the lane: as if Julia’s simple existence had caused a traffic jam in the smoothness of Kayla’s day. “You’re poisoning her against us,” she said to Julia.

“I’m representing my client,” Julia said. “You’re welcome to retain counsel.”

Kayla laughed the way we used to laugh when we were kids planning an ocean we could never afford to see. “Counsel,” she repeated, like the word itself was a luxury item with a price tag. “You always think you’re so above us.”

I thought about the time I taught her to braid, the afternoon sun turning our living room into a bright net we were caught inside. I thought about her hand in mine when a boy at the bus stop licked his thumb and pressed it to my cheek to smear the drugstore mascara, and how Kayla had turned and told him to eat dirt with such conviction he did. Love is history. Love is also math. On that hallway bench, I set the two beside each other and didn’t let nostalgia do any rounding. “I am not above you,” I said. “I’m simply not beneath you anymore.”

We didn’t hug. We didn’t promise to call. She left with the angry flounce of someone who has never carried a box all the way to the curb. I stood there a moment longer, letting the noise of the building wash over me until it turned to weather.

The days that followed were not dramatic; they were honest. Honest looks like grocery lists that include only what you can eat; it looks like sleep arriving without a fight; it looks like the small relief of a phone that doesn’t ring for a crisis you can solve in thirty minutes with your debit card. It looks like Dr. Levin saying, “Try replacing the sentence ‘I can’t stand it if they’re upset with me’ with ‘I can survive it if they’re upset with me.’” It looks like surviving it, and then one day forgetting what it was you thought you couldn’t survive.

On Sundays I walked to the Green City Market and bought too many peaches because I still haven’t figured out how to shop like only one person will be eating. I kept a bowl on the counter with three tulips—the blue ones if I could find them, otherwise white—and watched the light move over their petals like a quiet clock. Evan came by with coffee that tasted like the idea of cinnamon, and we talked about the kind of small things that used to feel like a luxury: which neighbor had adopted the three-legged pit bull; whether the old Polish bakery on Milwaukee would ever reopen; the way Wrigley sounded like summer even if you were just listening to the city through your window.

“Do you miss them?” he asked once, carefully, like a man setting a glass down far from the edge.

“I miss the idea of them,” I said. “The one I paid for.”

He nodded. “Ideas are expensive.”

We didn’t touch the word love. We let the air own it. There is a strange holiness in not naming something before it’s sturdy.

Cousin Leila started texting me recipes like that was a thing we had always done: her grandmother’s chickpea stew with too much cumin, a citrus cake that required the kind of patience I used to spend on other people’s fires. After the probate order posted, she called. “They’re telling people you stole the house.”

“I sold a house that was legally mine,” I said. “They forged my name on a withdrawal.”

“Everyone with a head knows,” she said. “But some people prefer the myth.”

“They always have.”

Leila scuffed something across her floor. “You know Aunt Gina said she thought your mom had practiced your signature? On the phone pad by the fridge?” She paused. “I told her that was a thing she could have mentioned earlier.”

“People love hindsight,” I said. “It lets them feel brave without having to act.”

We laughed in that tired way people laugh when the alternative is cursing the past into a shape that will never hold water. Then Leila said, “Come to dinner. No agenda. We’ll talk about anything except the Johnsons.”

At her place in Logan Square, the table was set like a calm argument: plates that didn’t match but were committed to the idea of being together anyway. She lives with a woman named Renata who builds cabinets with her hands and has the softest voice I’ve ever heard on a person who uses saws. We ate too much and then went for a walk under the el tracks where the concrete catches the city’s heat and lets it go reluctantly into the night. No one said the word forgiveness. No one said obligation. We said “Look at that mural,” and “Do you smell lilacs?” and “Remember the summer the hydrants were always open?” We built a different kind of family out of stories that asked nothing from me except to be present.

There were setbacks that didn’t feel like setbacks because they weren’t mine: a message from my mother forwarded from an aunt I haven’t spoken to since I was nineteen, the subject line a sermon, the body of the email a shopping list of ways I had failed her. “We forgive you,” she wrote at the end, the sentence shaped like a scold. I forwarded it to Julia, archived it, and then—because the body keeps its own score—I walked around the block until my heart returned to its steady metronome.

On a wet Thursday in May, the handwriting expert Julia had retained sent a report with the kind of dry authority only a person who loves penstrokes can muster. Letter formations inconsistent. Pen pressure irregular. Baseline slant variant with no precedent in known samples. It read like a poem about the way liars press too hard. I didn’t need the report to know the truth, but there was a justice in the documentation: proof that didn’t need me to be louder than the people who had learned to perform outrage like a profession.

I saw my father once in line at a Walgreens. He had a basket with aspirin, a bottle of shampoo, and a pack of socks like the ones he used to give us at Christmas because he believed practicality could substitute for intimacy. For a second he didn’t see me. When his eyes found mine, the years did a small and complicated dance: guilt, shame, the warm wash of habit that made me want to ask if he needed cash. I did not ask. “Hi, Dad,” I said.

He swallowed. “Soph.” The word wore out its single syllable on his tongue. “You look good.”

“I sleep,” I said, and meant, I don’t fund your comfort anymore.

He nodded at the basket like it might speak for him. “Your mother…” He stopped. He has always been a man of ellipses, beginnings that expect someone else to finish the sentence in the way that best suits him.

“I know,” I said. “I hope you’re okay.”

He looked down at the socks, back up at me, and then—because even small growth is still growth—he said, without asking, “I’m learning to be.”

“Me too,” I said.

When he made it to the cashier, I wanted to leave cash on the counter and run, the muscle memory in my hand twitching like a dream. I did not. I walked out into a drizzle that turned the city to watercolor and felt both lighter and heavier, which I am learning is what real goodbye feels like when you build it inside your life rather than on the back of a single dramatic scene.

Dr. Levin asked, “If your mother wrote you today and said exactly what you needed to hear, what would that be?”

“I don’t know,” I said, because the truth was I could write a hundred apologies for her and none of them would stick to my bones. “Maybe nothing. Maybe the sentence I needed had to come from me.”

“What sentence is that?” she asked.

“I get to choose who I am responsible for.”

We let the sentence sit between us like a guest who didn’t need entertaining. The air felt thinner in a good way, like the room had high ceilings I just hadn’t looked up to notice.

On the first hot day of June, Evan took me to the Garfield Park Conservatory because the city feels gentler when you’re surrounded by plants that were meant to live somewhere else and are thriving anyway. In the fern room, the air smelled like rain and patience. “They say this is what Chicago would feel like if the lake decided to climb out and shake itself off,” he said.

“Would we be kinder?” I asked.

“I think we’d be wetter,” he said, and I laughed in a way that startled a small child who looked at me like I had broken a museum rule.

We sat on a bench under a canopy of green so bright it felt like a dare and shared a bottle of water like people in movies share cigarettes. He told me about his father, who had been kind and then drunk and then kind again, which is a rhythm a child’s nervous system can’t grow straight inside. “I used to think it was my job to be easy,” he said. “Turns out I’m not a job.”

“Turns out I’m not a bank,” I said.

We didn’t kiss. We didn’t need a punctuation mark. Sometimes the best sentences end in a period that allows you to breathe.

I went to the Art Institute alone the next week and stood in front of the Caillebotte until the wet street was the only thing in my head. People filed past, earbuds in, galleries mapped on their phones like the museum was an airport with a direct flight to meaning. I stayed until my knees hurt. I thought about all the rooms I had stood in to save other people from weather and how long it had taken me to pull my own umbrella out of my bag.

July brought heat that made the city stick to itself. In the evenings, the neighborhood kids opened hydrants with a wrench that must have been passed from older boys to younger, the water pluming into the street like a surprise parade. I watched from my window with the lights off, the scene making me feel both ten and present, which I have come to understand is a kind of miracle. Someone played a radio loud enough that even the alley rats had to tap their feet. I ate a peach over the sink and thought about Ruth’s hands moving over the lids of jars until each one clicked.

There were letters, of course. Legal ones that arrived in envelopes with windows, and personal ones delivered by the internet with the speed and thoughtfulness of a thrown rock. My mother wrote a real letter on paper once, a thing so out of character I opened it at the counter like news. It was two pages of the past rewritten with her as the heroine and me as the ungrateful bystander. At the end, she drew a heart over her name like a teenager. I folded it back into the envelope and slid it into the drawer with the warranty and the list of things that belong to only me. Later, I threw it away. It felt less like betrayal and more like finally taking out a bag of trash you’ve stepped around for months.

I kept waiting for the anger to rise like a storm wall and slam back into me. It didn’t. What rose instead was a steady kind of clarity that did not require me to rehearse my argument. Boundaries do not ask for witnesses. They simply stand, wash after wash, until the coastline changes.

One night, Evan and I sat on my floor with takeout boxes balanced on our knees, watching a game without caring about the score. “Do you ever wish you had said it differently?” he asked.

“What?”

“The first no.”

I thought about the message at 11:51 p.m., about the way the phone lit up like a small cruel sun, about the hour after when my apartment had felt like a church with its doors locked from the inside. “No,” I said. “I wish I had said it sooner.”

He nodded and stole one of my fries and I let him. There are some thefts that are also gifts.

By August, my apartment had a table. Not fancy. Four legs that didn’t wobble, a top that could take a ring from a mug and not complain. I invited Leila and Renata and the neighbor with the three-legged dog and Evan and Molly from my office who has eyes like someone who tells the truth even when it hurts her. We ate too much again, which I am learning is the point. When everyone left, the room was a beautiful mess. I sat in the quiet and looked at the evidence of people who had chosen to be with me. I took pictures: the bottle with an inch of wine hiding at the bottom, a cloth napkin that slid off a knee and lay waiting to be discovered, a fork that had migrated to the windowsill because Renata talks with her hands. I didn’t post them. I wanted the moment to live where it happened instead of being shipped out to people who would click hearts without tasting the food.

In September, the court mailed a final statement of accounts, which is exactly as unromantic as it sounds and more satisfying than any apology I will never receive. Numbers lined up under headings; debits became credits; my name stopped appearing in places it didn’t belong. I held the paper in both hands and felt it weigh less than it should given what it carried away from me.

Sometimes I imagine a different version of my life where my mother learned the trick of loving me without requiring my disappearance as proof. In that life, we sit on a porch somewhere with a flag lifting in a soft wind, and she says, “I’m sorry,” and I say, “I know,” and the story closes its book with a sigh. That is not this life. In this life, I learned to say I’m sorry to myself for the years I spent being so good at accounting that I forgot to account for myself.

Winter returned like it always does, indifferent and complete. On the morning of the first snow, I stood at the window with a cup warming my hands and watched the city try to decide whether to become a postcard. For a minute the alley went quiet. Even the trucks softened. A woman in a red hat walked a black dog who refused to put its feet down properly; it high-stepped through the powder like a princess. I laughed out loud and then cried a little in that clean way crying can be when it doesn’t have to argue its case.

I went to Mount Zion with tulips that were not blue because winter doesn’t care what you prefer. I brushed the cold from Ruth’s name and told her about the table and the fries and the socks at Walgreens and the day the judge said, “The order will issue,” like a blessing. “I kept the bluebird,” I said. “I kept the quilt.” The wind came across the graves with the kind of bite that reminds you being alive is a job with excellent benefits.

On the train home, a mother across from me tried to quiet a toddler with snacks and songs and finally her phone. The little girl held the device like it was a star she could control. For a second—only a second—I wanted to lean across the aisle and tell the woman to hold on tight to the feeling of being needed. But I didn’t. We all learn in our own seasons. I looked at the city sharpening itself outside the window and thought, again, about keys.

I used to be the person who kept keys for other people—spare sets in bowls, passwords tucked into notes, my credit card number memorized by more relatives than I’m comfortable admitting. Now I keep my own in a dish by the door. When I drop them there at night, the little clatter feels like punctuation. Not an exclamation point, not a question mark. A period. The good kind. The kind that says: this sentence has ended exactly where it should.

A year after the message, the city thawed and then remembered itself with thunder. On the anniversary, I didn’t light a candle or make a speech to an empty room. I ordered good Chinese food and watched a terrible movie and fell asleep on the couch with a book on my chest like a cat. In my dream, I stood on the porch of the Birchwood house while strangers inside painted rooms I used to recognize. A woman I didn’t know waved at me through the window and then went back to her life. I woke with the kind of peace that doesn’t ask you to prove it.

If there is a moral, I suppose it is ordinary: the person you are responsible for is the one signing the checks with your name. If there is a miracle, it is quieter than I thought: forgiveness does not require reunion; accountability does not require spectacle; love does not require you to finance your own erasure. If there is a map, it fits in the palm of your hand and says nothing about north or south. It says: here. It says: now.

Sometimes I still open that first spreadsheet in my head and run my finger down invisible columns until I reach the place where the math stops being about them and starts being about me. The total at the bottom is not a number. It is a room with windows that face the morning. It is a table that doesn’t wobble. It is a name I sign for myself and a key I keep in my own dish. It is the smallest, truest extravagance I have ever allowed: a life I can afford because I am the only one who gets to spend it.