The first time the room noticed me all night, it wasn’t because I’d spoken. It was because the music stuttered mid–Sinatra. Through the…

Sinatra crooned from the hidden speakers, the kind of music my parents used when they wanted a room to forget what it was…

My mom set her mug down on the kitchen counter like the sound itself was a verdict. The morning sun slanted in through…

My sister texted at 6:41 p.m. on a Saturday, the kind of Saturday that still smells like cold air and cinnamon if you…

The first thing I remember is the little U.S. flag magnet on the bartender’s tip jar—red, white, and blue, chipped at the corner—tilting…

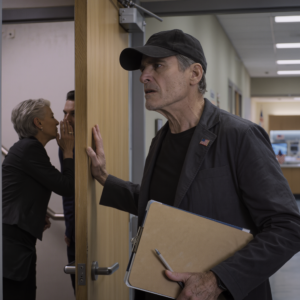

A knock hit my front door like a judge’s gavel—three sharp raps, precise, practiced. From across the street, I watched through the windshield…

At 4:00 a.m. on December 15, 2024, the phone rang through my dark kitchen like it had a badge of its own. Sinatra…

The courthouse lobby smelled like floor wax and burnt coffee, the kind you buy from a vending machine because your hands need something…

I didn’t drive four hours into the Colorado mountains to play referee. I drove because I needed silence—the kind you can only find…